By Martin

Forget the sell-off in the equity space, it was expected. It seems you can’t teach an old equity dog new credit tricks. It was the case in 2008 and again it looks like it is the case in 2011. Earlier this year I explained the fundamental differences between equity markets and credit markets in the post: “

A tale of two markets – Credit versus Equities“. We have a different DNA.

As I posted back in January 2011, in 2007, there was a big disconnect between credit markets and the equities markets. Volatility was falling, I argued, while credit spreads were simply exploding, with sometimes gigantic intraday moves, early indicators of trouble brewing? Lessons learned in 2011? I don’t think so. I also indicated in this previous post the following:

“The recent significant increase in credit spreads for many financials have been driven by the markets concerned about the ability of the weaker players to access credit at reasonable rates.”

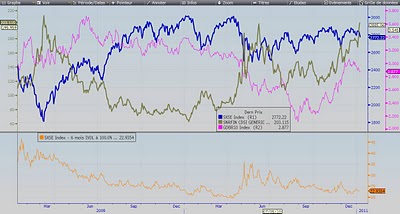

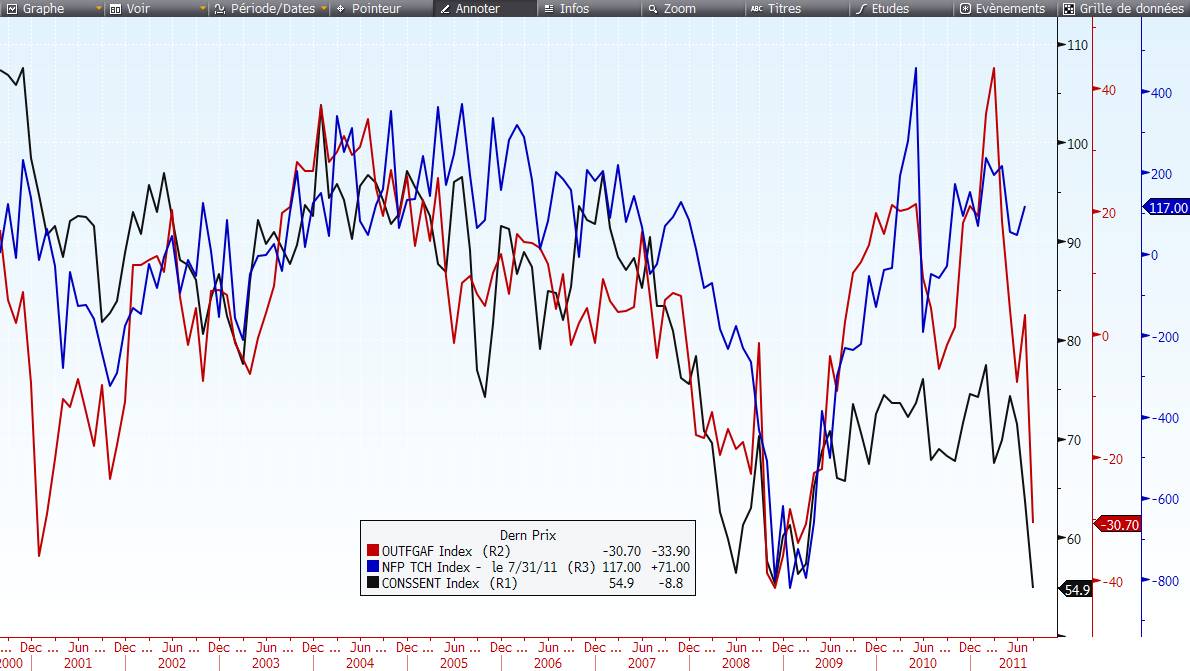

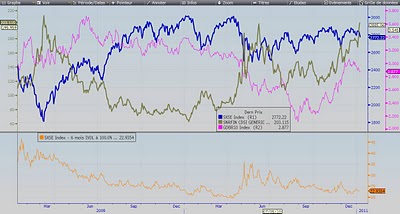

We had an interesting disconnect in January 2011 if you look back at the previous post, as indicated by the graph where you had Eurostoxx 50 (SX5E), Itraxx Financial Senior 5 year CDS index, German Bund (10 year Governement bond, GDBR10), and at the bottom Eurostoxx 6 month Implied volatility.

Here is the graph from January 2011:

At the time, European High Yield debt was tighter than Bank Sub Debt. It is not the case today.

Here is today’s update from the graph published in January 2011:

We can clearly see the acceleration in the flight to quality with the drop in the German 10 year government bond yield. Since March, the Itraxx Financial 5 year CDS has been creeping higher, and finally the Eurostoxx gave up.

But back to the subject, liquidity and to be blunt, I do not like what I am currently seeing, it is going to be a long post.

The Unknown

As we know,

There are known knowns.

There are things we know we know.

We also know

There are known unknowns.

That is to say

We know there are some things

We do not know.

But there are also unknown unknowns,

The ones we don’t know

We don’t know.

—Donald Rumsfeld, Feb. 12, 2002, Department of Defense news briefing

In a CreditSights report published on the 17th, I had the opportunity to peak through their report on European Banks and liquidity issues.

What I’ve learnt:

Banks have been still reluctant to disclose their liquidity and short-term funding positions, in effect, European banks have failed to learn the lessons from 2008. Although they have higher liquid assets and lower short-term funding reliance than in 2008, the lack of disclosure and market runours about their funding the market is gaining traction, hence the very high volatility in European Banks stock prices and widening CDS spreads. But, ECB and other Central banks are still providing liquidity support, which alleviates somewhat funding concerns.

Truth is liquidity assessment were not included in the latest EBA (European Banking Association) stress tests we had in July. Without hard data and hard facts, how do you refute rumours and reduce interbanking lending pressures? You can’t. One would have thought that after the 2008 debacle, lessons would have been learnt, and that greater transparency is a must.

CreditSights is describing what you can find or not…from the most recent financial information, i.e. banks’1H11/2Q11 earnings reports:

The bad:

“A maturity breakdown of funding liabilities in European banks’ interim reports is rare. This makes impossible to calculate expected cash outflows.”

The good:

“An increasing number of banks disclose their stock of prime liquid assets (including cash, government securities and other securities eligible with central banks).

Creditsights to add:

“We believe liquid assets are typically much higher than they were in 2008 in relation to banks’ balance sheets, while short-term funding is typically smaller as banks have focused on lengthening their maturity profile. However, it is difficult to find comparative data.”

Another issue is the lack of disclosure of the liquidity coverage ratio:

From CreditSights:

“Hardly any banks are yet disclosing their “liquidity coverage ratio” (LCR). Under Basel III and CRD4, banks will have to comply with a new liquidity coverage requirements from 2015, after an observation and review period beginning in 2011. The aim is to ensure that banks have sufficient high quality liquid assets to withstand an “acute stress scenario” lasting for 30 days. The requirement would be a minimum LCR of 100%. In other words, the stock of high quality liquid assets should be sufficient to cover 30 days of cash outflows in stressed conditions.”

and Creditsights to add on the subject:

“In current market conditions, this ratio would be a useful indicator, but it is impossible to calculate it accurately for European banks, which are reluctant to disclose it before the regulators have finalised the definitions.”

The circularity issue weighting on liquidity:

In highly-indebted Eurozone countries, the issue of circularity comes from the high correlation with their sovereign creditworthiness, meaning they are experiencing very high level of stress on their current funding.

Conclusion for the banks in the peripheral countries:

The ECB is currently the ONLY SOURCE of wholesale funding for these smaller banks and have therefore prevented aggressive deleveraging to happen and liquidations.

According again to CreditSights in their report, Italy’s net reliance on the ECB remained low in relation to its large banking system’s total liabilities (2% at the end-July). But, gross liquidity provided to Italian banks in the ECB’s main and long-term refinancing operations virtually doubled from 41 billion euros at end of June to 80 billions euros at end of July 2011. It never even reached 50 billion euros since the end of 2008.

There is a rising risk of a credit crunch in Southern Europe.

A widening gap between Euribor and OIS is indeed a sign of stress in the interbank market. The full allotment provided by the ECB is mitigating so far liquidity concerns.

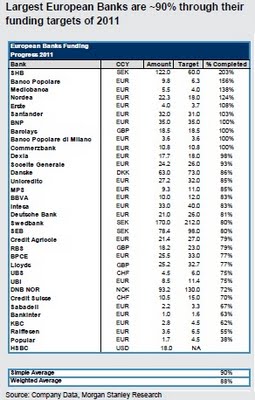

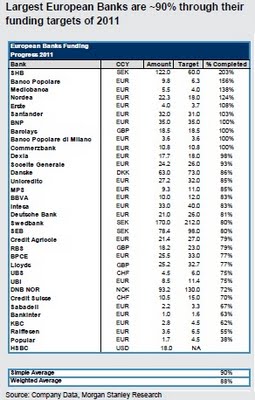

According to another report, this time by Morgan Stanley (European Banks – The Stress in bank funding and policy options – 15th of August 2011), European banks are starting from a better position than in 2008 given their latest funding survey which suggests that “Europe’s leading banks are on average issued around 90% of their term funding needs for 2011 with significant liquidity pools, better solvency and resolute ECB commitment to support the system”.

What we learn from this additional Morgan Stanley report:

“ECB support for bank funding is deep; it is also growing notably in Italy. We have regularly shown the periphery is already dependent on the ECB: 20% of Greek banking assets, 15% of Irish, 8% of Portuguese; 4% of Cypriot are funded at ECB window.”

Why liquidity matters again? Because bank funding is a key source for bank earnings, ability to lend, therefore a drag on the economic recovery if it doesn’t happen smoothly. While the US boast a Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Programme (TLPG), a similar mecanism is not currently available in Europe so far.

With the markets currently shut down with the ongoing volatility and turmoils, long term funding is beginning therefore to be a concern and the consequences very easy to understand, but unfortunately maybe not so easy to understand for our European politicians.

Lack of funding means that bank will have no choice but to shrink their loan books. If it happens, you will have another credit crunch in weaker European economies, meaning a huge drag on their economic recovery and therefore major challenges for our already struggling politicians.

As a reminder, 50% of banks earnings for average commercial banks come from the loan book: no funding, no loan; no loan, no growth; and; no growth means no earnings.

So what does that all lead to, very simple, an American solution, to European woes, namely a European TARP programme in conjunction with a European TLPG programme.

Given the strong correlation between sovereigns and their banks, as recently shown in the CDS markets for both Sovereign spreads and Financial Subordinated CDS for some European banks in the peripherals, it is a serious matter to consider, and no offense to our equity friends complaining about a nasty sell-off (believe me equity friends, you ain’t seen nothing yet, like in 2008), if the funding issues we mentioned here are not been addressed, it could get worse, much worse.

I posted this several times, but, remember, a bank is a leverage play on the economy, it is the second derivative of a sovereign. In fact, according to Morgan Stanley, the correlation has been 0.8 with peripherals and European banks in the last 6 months (so what were our equity friends thinking?).

And if our equity friends don’t believe this, then maybe these few Itraxx 5 year CDS charts will tell them more about what is going on out there and it ain’t pretty in the credit space:

Itraxx Crossover 5 year index (High Yield):

Hey! That W sign on the chart, technically is that a buy sign? I’m afraid not equity friends.

Bank Risk rising? Bank Risk soars above credit crisis peak – Bloomberg – Chart of the Day – Itraxx Financial Index of CDS linked to 25 banks and insurers:

Fact: “The cost of insuring senior bonds of European banks against default is higher than when Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. collapsed, as funding dries up and concern mount lenders won’t get bailed out again” – Bloomberg

What we have is a 37% increase from July 28 to 237 bps as of today. It was 149 bps when Lehman went down in September and peaked at 211 in March 2009.

So yes, I don’t like what I am seeing and here are some more food for thoughts:

Point 1:

Yesterday according to Bloomberg, Lars Frisell chief economist at Sweden’s financial regulator told Swedish banks should step up preparations for a freeze in interbank debt markets as Europe’s debt crisis is intensifying.

“It won’t take much for the interbank market to collapse,” Frisell said yesterday in an interview in Stockholm.

He added: “It’s not that serious at the moment but it feels like it could very easily become that way and that everything will freeze.”

And guess what I saw today on the 10 year Swedish Goverment bond yield? A massive 22 bps tightening move, which incidentally is the biggest tightening move of the day in the European bond market and I don’t like these kind of moves:

10 year Swedish bonds breaking the 2% level yield down.

The three-month Stockholm interbank lending rate reached 2.59% yesterday, the highest since December 2008. The rate rose to more than 5 percent in 2008 as the market froze following the Lehman collapse.

Point 2: From Bloomberg article today – By Chitra Somayaji – Aug. 18 (Bloomberg)

“U.S. regulators are stepping up scrutiny of local operations for Europe’s largest banks on concern that the region’s sovereign debt crisis may lead to funding problems, the Wall Street Journal reported today. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has been holding talks with the lenders and sought information about their access to funds to maintain operations in the U.S., the Journal said,citing people it didn’t identify. The regulator has also been asking some lenders to overhaul their structure, it said. Policy makers, who aim to avert a repeat of the 2008 global financial crisis, are concerned that Europe’s debt problems may curtail the banks’ ability to fund loans and meet their obligations in the U.S., or lead them to siphon funds from the U.S., the newspaper said.”

Point 3: Philly Fed – you know the score by now:

More fun?

Let’s compare Michigan Confidence/Philly Fed and NFP (Nonfarm Payrolls):

Point 4:

Again on Bloomberg, Austria is joining Finland in asking Greece for collateral in exchange of new emergency loans:

“It always was our position in the council that if there is a collateral setup, Austria will participate,” Harald Waiglein, a spokesman for Austria’s Finance Ministry.

“The Netherlands, Slovakia and Slovenia have also expressed interest in getting collateral should the Finns manage to strike a deal, Waiglein said.”

“The agreement requires Greece to deposit cash in a state account that Finland will invest in AAA rated bonds. The interest generated will raise the amount, which has yet to be disclosed, to cover Finland’s bailout contribution. The bilateral arrangement needs approval from other euro members,Finland’s Finance Ministry said.”

Another risk of European political bickering in the coming weeks. Stay tuned.

And finally, and because it has been a long day and some people, once again, are aging in dog years this week, including me, I give you one last chart, supportive of the deflation story, Swiss 30 years bond versus Japanese 30 years bond:

To be continued!