By Thomas Mayer

This article

is by Dr. Thomas Mayer, Chief Economist for Deutsche Bank Group and Head of Deutsche Bank

Research. Before Dr. Mayer joined Deutsche Bank in 2002, he worked for

Goldman Sachs in Frankfurt and London (1991-2002), and for Salomon Brothers in

London (1990-91). Before moving to the private sector, he held positions at the

International Monetary Fund in Washington D.C. (1983-1990) and at the Kiel

Institute for the World Economy (1978-82).

We welcome Dr.

Mayer to the Daily Capitalist.

Introduction

The financial crisis has led many people to doubt the merits of free markets

and a liberal economic regime. They blame markets for the financial and economic

crisis and demand tighter regulation and, in effect, more central planning by

governments as a remedy. We shall argue that both the analysis on which this

view is based and the policy recommendations are flawed. This crisis has been

caused by too much reliance on the effectiveness of economic and financial

planning. Failure of the “liquidationists” to overcome the Great Depression of

the early 1930s prepared the ground for an era of interventionist economic

policies. Modern macroeconomics and finance nourished the belief that we can

successfully plan for the future. But the present crisis teaches us that we live

in a world of Knightian uncertainty, where the “unknown unknowns” dominate and

our plans for the future are regularly thwarted by unforeseen and unforeseeable

events. We have suffered from “control illusion.” We need to recognize the

limits of planning for the future and the superiority of a market-liberal

economic order, where states, firms and individuals can be held liable for the

financial decisions they have taken.

The

predecessor of today’s crisis

To develop our point we first take a look at the historical predecessor of

today’s financial crisis, the depression of the 1930s. During the 1920s easy

monetary conditions and an exaggerated appetite for risk, evidenced by extreme

leverage in the popular equity trusts, fuelled the build-up of a stock price

bubble. When monetary conditions were tightened eventually, the edifice of

leverage came down and the stock market crashed in October 1929.

At the time, the authorities took the crash in their stride. Many policy

makers felt that the crash and a possible recession afterwards were needed to

eliminate the excesses and imbalances that had built up during the roaring

twenties. Andrew Mellon, then US Secretary of the Treasury, brought this view to

the point when he said:

“…liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers, liquidate real

estate… it will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and

high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life.

Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up from less

competent people.” (Hoover, Herbert (1952). Memoirs. Hollis and Carter. p. 30).

Inspired by Mellon’s attitude, those sharing the idea that a recession was a

“cleansing event” were later dubbed “liquidationists.”

The “liquidationists” could claim theoretical

support for their view from the Austrian school of economics around Joseph

Schumpeter and Friedrich von Hayek, which built its view of the business cycle

on the work of the Swedish economist Knut Wicksell. Wicksell distinguished

between a natural rate of interest, which reflects the return on investment, and

a market rate, which reflects the borrowing costs of funds charged by the banks.

When the market rate is below the natural rate, companies borrow to invest and

the economy expands. In the opposite case, investment is reduced and the economy

contracts.

The Austrian school used this idea to develop a theory of the business cycle

that puts the credit cycle in the centre (see picture left). Low interest rates

stimulate borrowing from the banking system. The expansion of credit induces an

expansion of the supply of money through the banking system. This in turn leads

to an unsustainable credit-fueled investment boom during which the “artificially

stimulated” borrowing seeks out diminishing investment opportunities. The boom

results in widespread overinvestment, causing capital resources to be

misallocated into areas which would not attract investment if the credit supply

remained stable. The expansion turns into bust when credit creation cannot be

sustained – perhaps because of an increase in the market rate or a fall in the

natural rate – and a “credit crunch” sets in. Money supply suddenly and sharply

contracts when markets finally “clear,” causing resources to be reallocated back

toward more efficient uses.1

The liquidationist approach to economic policy in the aftermath of the 1929

stock market crash – for which Mellon became the symbol – accepted the downturn

in the early 1930s as inevitable. What they missed was that extreme risk

aversion can keep the market rate above the natural rate even after ?the

rottenness? has been “purged out of the system.” Franklin D. Roosevelt, who beat

Hoover in the 1932 presidential elections, seems to have intuitively understood

this problem. Perhaps the most important action Roosevelt took shortly after his

inauguration in early 1933 was to guarantee bank deposits. As a result, cash

that people had hoarded under their mattresses came back to the banks and

improved their liquidity situation. When the Roosevelt administration later in

the year recapitalized banks, credit extension picked up again and the economy

recovered. It is interesting that there was no big fiscal policy stimulus in

1933 – the famous New Deal was felt only later. Hence, contrary to conventional

wisdom, the spark that ignited the recovery of 1934 was the turn in the credit

cycle (see chart).

The experience of the depression and the Roosevelt recovery induced John

Maynard Keynes to launch a heavy attack on the Austrian school. In his General

Theory, written in 1935, he made a strong case for government intervention.

Fiscal policy should come to the rescue when the public feared deflation and

hoarded money. Many students of economics today believe that it was the

application of Keynes’ theory that ended the downturn of 1930-33. We do not

agree. In our reading of events it was the policy-induced turn of the credit

cycle that did the trick. Hence, the recovery of 1934 was more “Austrian” than

“Keynesian”. Let us be clear: The liquidationists were wrong to allow the

depression to happen as they failed to recognize that fear can beget fear.

Roosevelt recognized this when in his inaugural speech he said “the only thing

we have to fear is fear itself,” and he was right to intervene and stabilize the

banks. But what he did – opening the credit markets – is what follows from an

Austrian reading of the business cycle.

The Austrians have warned that a policy-induced extension of the credit cycle

before all excesses have been eliminated in the economy will only delay the day

of reckoning. But also they would have had to conclude that after the depression

of 1930-33 one could hardly still see “excesses” in the economies of the western

world. Nevertheless, the economy tanked again in 1937 when the monetary and

later fiscal policy support was withdrawn. Most economic historians argue that

the period of economic instability in the US only ended towards the end of the

1930s when the country prepared for war. The British historian Niall Ferguson

has even argued, that Germany got out of the depression ahead of the US because

of its earlier and more aggressive preparations for war. It seems that only in

the anticipation of war the “fear of fear itself” ceased to be a de-stabilising

factor in economic developments.

The historical review of the Great Depression leaves us with a disturbing

conclusion: The Austrian credit cycle theory seems to have a better fit to

events than Keynes’ theory of the liquidity trap and power of fiscal policy (see

chart). What the Austrians seem to have missed is that an economy paralyzed by

extreme risk aversion may need a jolt by confidence-building economic policy

measures. But this was not what most economists and policy makers concluded.

Lessons

from the Great depression: “Over to governments…”

At the end of WWII a number of western intellectuals and economists flirted

with Soviet-style central planning. After all, the Soviet Union had prospered

during the 1930s while the capitalist countries had been in crisis. Did this not

prove that their economic model was superior?

Having lost the intellectual battle with Keynes and followers in the 1930s,

the Austrians made a last stand against central economic planning with Hayek’s

powerful book “The Road to Serfdom” published in 1946. They won the war of

principles and the western world did not subscribe to Soviet-style central

planning, despite the allure this model was exercising on many intellectuals

after WWII. Even Keynes sided with the Austrians as far as the high ground was

concerned and wrote to Hayek: “In my opinion it is a grand book … Morally and

philosophically I find myself in agreement with virtually the whole of it: and

not only in agreement with it, but in deeply moved agreement.”

Nevertheless, the Austrians lost the battle over economic policy in the

post-WWII western countries. Keynes’ idea of “demand management” through fiscal

policy became the mantra there after the war. Somewhat belatedly, in 1971 when

he ended the link of the US Dollar to Gold, even Richard Nixon is reported to

have said “I’m now a Keynesian in economics.”

From the 1950s to the end of the 1970s western economic policy makers used

and abused fiscal policy as an economic management tool. Governments were quite

happy to raise borrowing in economic downturns, but generally reluctant to bring

it down in upturns. Towards the end of the 1960s, the use and abuse of fiscal

policy created strains on government finances that could only be eased by the

monetization of government debt. As a consequence, Richard Nixon on August 15,

1971 suspended the link of the USD to gold, and in effect launched the post-WWII

system of fiat money.

During the post WWII period of the implicit gold standard under the

Bretton-Woods System (where the USD was supposedly as good as gold), there was

hardly any room for pro-active monetary policy (which, however, did not prevent

the US government to use the money printing press as an auxiliary funding tool).

This changed drastically after Nixon’s decision of 1971. The result was a bout

of inflation as government debt and deficits were financed in part by the money

printing press. As both growth and inflation disappointed, the word

?stagflation? was coined to describe the economic conditions of the 1970s.

…

“over to the central banks”

The failure of the young new fiat money regime was that it lacked a monetary

anchor. As a result, monetary policy ended up accommodating fiscal policy and

wage policy developments. This was eventually recognized by policy makers in the

early 1980s. In the seventies, Milton Friedman had proposed limits on the

expansion of money supply and laid the ground for the introduction of

independent central banks. As Stagflation killed the idea that there was a

trade-off between inflation and unemployment, the time of monetarism had

arrived. Federal Reserve Chairman Volcker used the monetarist demand to “gain

control over the money supply” as a justification to engineer a deep recession

that brought inflation down. Hence, the early 1980s were a period of repentance

for the sins of Keynesianism committed in the late 1960s and 1970s. With the

development of the theory of rational expectations and efficient financial

markets, the pendulum seemed to swing back from the constructivism of economic

policy before to a more market liberal regime.

But the straitjacket intended by Friedman for monetary policy did not hold

long. In the course of the 1980s monetary policy freed itself from the Friedman

straitjacket and turned pro-active. The great champion of this approach to

monetary policy was Alan Greenspan, who followed Volcker in 1987.

The 1987 stock market crash was the first application of the proactive use of

monetary policy. To fend off recession risks, Greenspan cut interest rates. The

therapy worked and instead of decelerating the economy accelerated during the

late 1980s. The next occasion to apply the Greenspan method came in the wake of

the savings-and-loans-crisis at the end of the 1980s, which contributed to the

recession of 1990-91. Again, the Greenspan Fed cut interest rates to support the

economy and again succeeded in mitigating the downturn. In the following years,

the Greenspan method was applied again to fight the Asian emerging market and

LTCM crisis of 1998 and again when the dot.com bubble burst in 2000-2002. Until

the great financial crisis that began in 2007, it seemed that the Greenspan

method, the pro-active use of monetary policy to fine-tune economic

developments, had succeeded in abolishing the business cycle as we knew it. Thanks to the art of central bankers, the age of the Great Moderation had

arrived.

The great financial crisis that erupted in 2007 uncovered the Great

Moderation as a great illusion. Nevertheless, the old reflexes led to the

combined deployment of monetary and fiscal policy on a so far unprecedented

scale. As the excessive leverage built up in the illusory age of the Great

Moderation was unwound, the crisis moved from the US sub-prime mortgage sector

to the money markets, the banking sector and more recently to the public sector

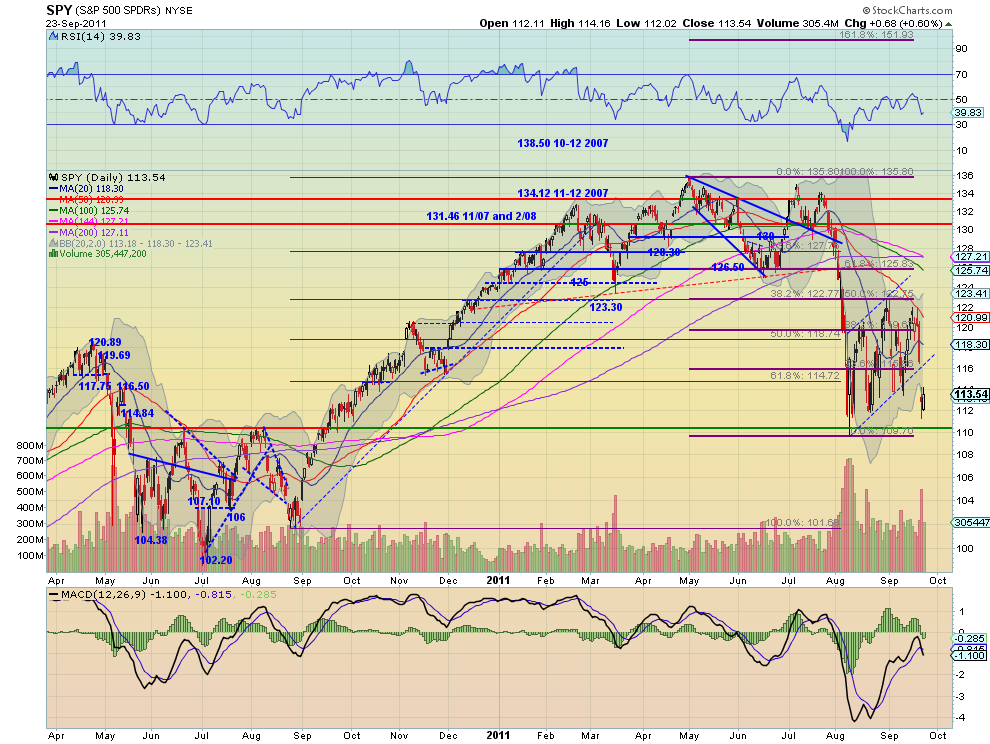

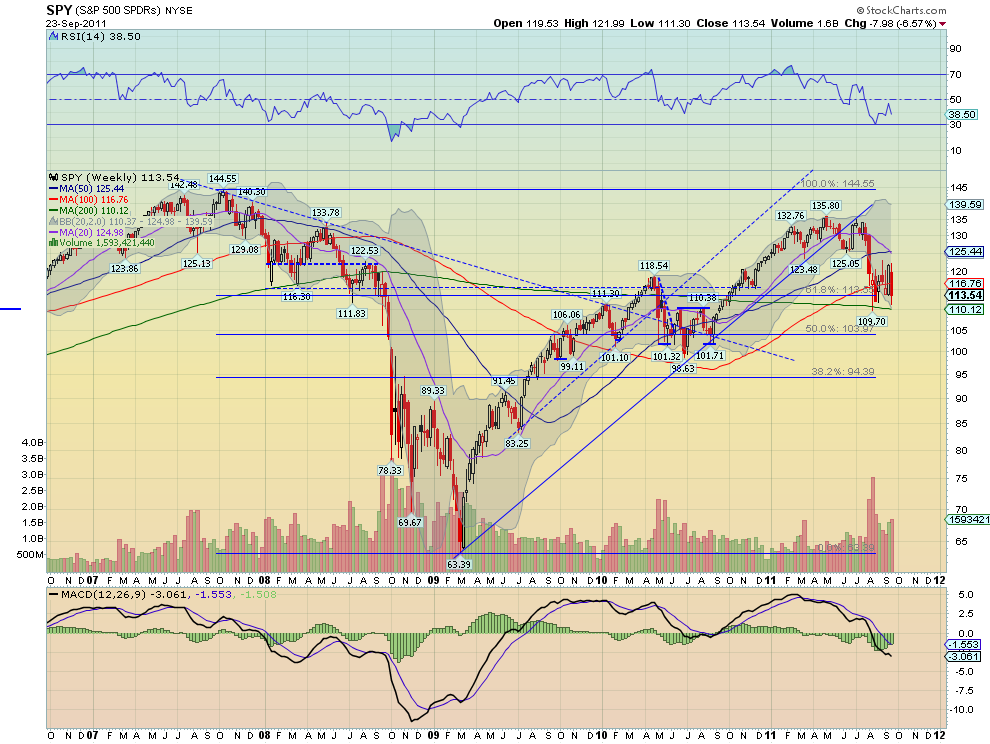

(see chart). The principle has been to shift the unbearable burden of debt from

weaker to stronger shoulders and lower debt service costs through monetary

policy induced interest rate cuts. But in this process the previously strong

shoulders have also been weakened. Somehow the old tricks seem to have lost

their magic, and the crisis triggered by massive de-leveraging appears to be

getting out of control.

The

theory behind “Greenspanism”

What was the major flaw that led us into this crisis? The belief that even in

a world of uncertainty economic and financial outcomes could be planned was in

our view a major contributor. The assumptions of rational expectations and

efficient financial markets laid the ground for overconfidence in the ability of

policy makers, firms and individuals to successfully plan for the future despite

the uncertainties surrounding us.

At the macro level, rational expectations and efficient markets theory laid

the ground for inflation targeting by major central banks, which replaced the

monetary targeting of the early 1980s. The economy was expected to grow in a

steady state, if only the central bank ensured stable and low consumer price

inflation. The overconfidence in the power of the central bank led Paul Krugman

to claim in the late 1990s:

“If you want a simple model for predicting the unemployment rate in the

United States over the next few years, here it is: It will be what Greenspan

wants it to be, plus or minus a random error reflecting the fact that he is not

quite God.”

When individuals had rational expectations and markets were efficient there

was no need to worry about asset markets or regulate financial markets. After

all, how could central banks or regulators know more than the market when market

prices reflected all available information about the future? Anyone questioning

the wisdom of the ruling paradigm was regarded as old-fashioned by the academic

cardinals of the Church of Anglo-Saxon economics, which has reigned supreme. In

retrospect, it seems a bit odd that academics overlooked financial markets’

obsession with central banks and the cult status they awarded central bankers.

How could financial market participants hang on the lips of central bankers,

when they so efficiently processed all available information in real time? But

economists were too enamored with their theories to dwell much on such

oddities.

At the micro level, rational expectations and efficient markets theory laid

the ground for many highly leveraged financial products and risk management.

Financial market participants saw only “known unknowns” that could be quantified

with probability theory. In a world of “known unknowns” they felt that there was

little need for contingencies for the truly unforeseen, the “unknown unknowns”.2

Hence, it seemed fully appropriate to raise leverage to the extreme. After all,

risk managers could calculate continuously and real time the value that could be

lost when the unknown happened. The feeling of being in control – of being able

to plan ahead with good, if not perfect, foresight – laid the ground for the

extremely high leverage that was built into financial products and the balance

sheet of financial firms.

After

the burst of “control illusion”

The collapse of these theories enforces the radical reduction of leverage. If

we cannot anticipate the range of future outcomes with a relatively high degree

of certainty, we need more slack and buffers in the system for unforeseen

events, and hence cannot afford high degrees of leverage.

The helplessness of the economic profession in the face of the present crisis

manifests itself by the recommendations of prominent economists for

ever-stronger incentives for a renewed increase of leverage. They advise that

fiscal policy turn expansionary again, central bank policy rates be kept at zero

for a long time, and central banks purchase financial assets.

At present the central banks fight the reduction in leverage with the

issuance of ever more central bank money. As outside money implodes inside money

explodes. For now, the aim to reduce leverage depresses asset prices and leads

to a flight into money. But the more the central banks succeed to replace the

reduction of outside money through de-leveraging by an expansion of inside

money, the more likely becomes the monetization of outstanding debt.

The desperate attempt to avoid an economic crisis caused by the necessary

de-leveraging could eventually lead to a crisis of the fiat money system itself.

On August 15 this year, the fiat money system celebrated its 40th birthday.

Since Nixon cut the dollar’s link to gold on August 15, 1971, the dollar has

depreciated by 98% against gold (see chart). Depreciation came in two stages:

First during the 1970s, when the excess supply of US Dollars created towards the

end of the BW-System and at the beginning of the new fiat-money system boosted

consumer price inflation, and secondly after the implosion of the credit-driven

?Great Moderation? as of 2007, when bad assets started to move from private

sector via public sector to central bank balance sheets.

When fiat money fails it may well be replaced by money backed by real assets

that cannot be augmented with the stroke of the pen of central bankers. How

could this happen? One possibility – which at present may sound a bit like

science fiction – would be for China and other big EM countries to peg the value

of their currencies to a basket of commodities. It would then be up to the

industrial countries to try to stabilize their currencies against the Yuan, or

accept the inflation that goes along with secular depreciation.

To

conclude:

Modern macro- and financial economics are based on the belief that economic

agents always hold rational expectations and that markets are always efficient,

in other words, that the earth is flat. We now find out that this is not true.

There are elements of irrationality and inefficiencies in the behavior of people

and markets. Therefore we need to dump the flat-earth theories promising that

economic and financial outcomes can be planned with a high degree of certainty

and need to look at other theories that accept the limits of our knowledge about

the future. A revival of Austrian economics could be a good start for such a

research programme.

Unfortunately, however, the battle cry of the public and politicians is for

more regulation: regulate banks, regulate markets, regulate financial products!

But those who push for blanket regulation suffer from the same control-illusion

that got us into this crisis. In our view, instead of more regulation we need

more intelligent regulation. At the heart of such regulation must stand the

simple recognition that we can at best tentatively plan for the future and must

feel our way forward in a process of trial and error.

In a world where we need to reckon with “unknown unknowns” – in a world where

Knightian uncertainty reigns – financial firms and investors need larger buffers

to cope with the unforeseen, i.e. more equity and less leverage. In a world,

where markets are not always liquid but can seize up in a collective fit of

panic, financial firms and investors also need a greater reserve of liquidity.

Regulation can help to achieve both objectives, but it needs to realize its

limits. Regulation will create a false sense of security, unless firms and

investors have the incentives to follow sound business practices. The best

incentive to do so is to make failure possible. Hence, we need effective

resolution regimes for financial firms.

In a world where people have imperfect foresight and do not always behave

rationally, and markets are not always efficient, we need to accept that

economic policy cannot fine-tune the cycle. All that policy can do is to lean

against excessive exuberance and depression during the credit cycle and help

avoid the excessive swings of risk appetite that we have seen over the last 10

years. It is unhelpful to pro-actively manipulate the market rate to achieve

certain economic growth objectives. Instead we should try to create the

conditions for a steady development of credit by allowing the market rate to

closely follow the natural rate. When accidents happen, we need to prevent that

“fear of fear itself” perpetuates economic crises by ensuring that the banking

system is capable to satisfy the demand for credit.

Finally, economists should be more humble. For too long we have tried to be

like natural scientists. Like they we like to develop our theories with the

method of deduction – start from a few axioms and describe the world in

mathematical terms from there. This was a little presumptuous, to say the least.

We need to realize that we are to a significant extent a social science. Social

scientists, like historians, use the method of induction. They observe, and then

develop tentative descriptions of the world from these observations. Because we

did not pay enough attention to economic history and relied heavily on formal

models of the economy we repeated a number of the mistakes that caused the Great

Depression.