Markus Bergstrom writes: It's an eerily familiar story. Shortly before the American housing bubble burst, pundits across the globe argued that the world had reached a new plateau of economic growth, where the old rules of economics no longer applied — "this time it's different." The same has been said about the current boom in China, specifically with regards to its large degree of top-down state control over the economy, which somehow enables it to ignore the laws of economics.

Indeed, this notion seems plausible according to traditional Keynesian aggregates. After all, China's GDP growth recovered in record time and at record pace from the global slowdown in 2008, hitting a staggering 10.7 percent toward the end of 2010. While some of this growth certainly comes from true economic development, a substantial portion is driven by monetary expansion, government "stimulus," and a massive, unsustainable real-estate bubble.

In 2008, in order to get back to postcrisis growth levels, the Chinese government prescribed a favorite statist remedy for times of economic hardship: monetary expansion. This was "necessary" in order to increase domestic investment and consumption, as well as to compensate for the slowing down in exports. In November 2008 the government also announced $586 billion worth of "investment" with the very same purpose.

However, when governments claim to be "investing" in something, one should always substitute it for "spending" or "printing money." As governments rarely spend money with the hope of reaping a profit, there's no way of knowing whether it was put to productive use or not. Even when profit-and-loss calculations guide these "investments," the capital still comes from forced taxation or inflation rather than voluntary savings. Thus it's still impossible to determine whether the money could have been spent on something better.

Hello, Anybody Home?

Well-known Austrian investor Jim Rogers has long played down speculations about a major Chinese bubble. He argues that while real-estate prices in some coastal cities are overheated, a cool-down of these would leave a slight dent on Chinese growth rather than result in a major slump. The rest of the country, he says, is

"hardly in a bubble."

Another well-known Austrian investor, Doug Casey, is

a lot more pessimistic, arguing that China "is in an unbelievable real estate bubble," which will cause "millions of Chinese — and the banks that lent them money — [to] lose everything."

There is certainly good reason to be concerned about China. A study conducted last summer by the Beijing University of Technology reported that a typical Beijing flat costs a staggering 22 times the average income in the city, while The Telegraph reported in December that the same figure for the city of Shenzhen is 18. On a national level, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) concluded last year that a typical Chinese property costs 8.8 times the average income. Compare this to just 5.5 in the United Kingdom in 2007 and 4 in 2009. In the United States, home prices peaked at a little over 5 times average income during its housing bubble, according to the S&P Case-Shiller Index.

A housing development in Ordos

As in the United States, the Chinese real-estate market is plagued by overconstruction, and not just in megacities like Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen. Brand-new ghost towns have sprung up all across China in recent years, the most famous of which is perhaps

Kangbashi in Ordos, Inner Mongolia. That city's housing capacity can currently accomodate well over 300,000 residents, yet only one tenth of that number

actually live there. Numerous other

lesser-known cities also boast swaths of high-rise apartments and majestic public buildings while appearing to be entirely devoid of residents.

Jim Chanos of Kynikos Associates claims that the new office space currently being constructed in China is enough to provide a five square-foot cubicle for every single citizen in the country. And that's just corporate real estate.

Finance Asia reports that some 64 million homes and apartments across China have sat empty for the past six months, enough to house 200 million people — 15 percent of the country's entire population. Along the same lines, a study conducted in 2007 by the Beijing Union University found that 27 percent of all newly sold apartments in over 50 different residential areas in Beijing remained unoccupied.

Why, then, is this mad overproduction continuing? After all, such massive discrepancies between units produced and units actually inhabited should result in falling prices. However, most new real-estate developments are actually snapped up

before they're even built. The buyers are usually speculators who refrain from even renting out the properties, hoping instead that they will yield even higher profits once flipped in pristine condition in the future. Bill Powell of Fortune recalls a neighbor in Shanghai who has bought a staggering 43 homes in just three years for this exact reason.

This absurd demand is in turn enabled by the aforementioned credit expansion. Officially, Chinese M2 grew by 58 percent between November 2008 and December 2010, while total bank lending (including informal lending) is said to have

doubled in 2009 compared to 2008.

Monetary Aggregates for China (measured in 100 million Yuan)

Source: The People's Bank of China (Central Bank of China)

A contributing factor to the real-estate mania is that, to most Chinese, real estate is the most lucrative and (seemingly) the safest investment option available compared to the alternatives; bank deposit rates are below CPI inflation, domestic stocks and other equity have performed poorly in recent years (to say the least), and capital controls still prevent citizens from investing overseas.

[1]More than Meets the Eye

Of course, overproduction and overpriced property weren't the only factors behind the American financial crash. Another major ingredient was the house of cards that made up the American mortgage market, which, at first glance, looks considerably different in China. For example, the down payment requirement for first homes is 25 percent, while the same figure for second homes is 60 percent (up from 50 percent in November last year) — third homes and everything beyond that require all-cash financing. Furthermore, reserve requirements for major Chinese banks were raised to 19.5 percent in January, following several increases in 2010.

Yet these factors pale in significance when viewed against China's huge informal economy. For example, recent estimates by Fitch Ratings suggest that China's banks lent out some 30 percent more credit (informally) than the government-regulated target of 7.5 trillion yuan ($1.1 trillion) in 2010. This comes despite the major curbing efforts by the government, as well as the fact that the four biggest banks in China are all — ironically enough — state-owned.

Rather than reducing the cash flow, the tighter regulations have simply encouraged banks to get

creative about their credit pumping. By repackaging and selling off loans to state-owned trusts and asset-management companies, banks have been able to keep their true lending at about the same levels as before while simultaneously staying below their official quotas. At other times, the banks have

turned loans into investment products and sold them to private investors, much as American investment banks did during the 2000s.

The situation is not made easier by China's lack of property rights in land, all of which is owned by the government and leased out to private and state-owned companies through so-called land-use rights. In turn, the sales of these rights constitute a vital revenue stream for local governments, providing powerful incentives for them to help spur the real-estate boom. This adds another explanation to the ghost towns all across China. Many local governments will find themselves in economic peril as revenue dries up.

Some may point out that China has both higher household savings and less private and public debt than the United States, which will help soften the blow from a real-estate slump. This is true to some extent, but things are not as simple as they first appear.

For example, Ernst & Young estimated as far back as 2005 that the total bad debt held by China's banks was then close to $1 trillion. The number today is probably several times that, given the fact that lending has exploded in the last two years. Mortgage levels are also increasing rapidly: almost

half of all residential properties sold in 2009 were funded by bank loans; in 2007 it was only 20 percent.

Another example comes from Professor Victor Shih of Northwestern University's 2009 study of China's public debt. He concluded that it is more likely to be somewhere around 40 percent of GDP, rather than the official 20 percent. Even the director of one of China's state-owned research institutes put the public debt at an estimated 50 percent last summer.

Hence both public and private debt could equal a substantial portion of China's $5.7 trillion GDP.

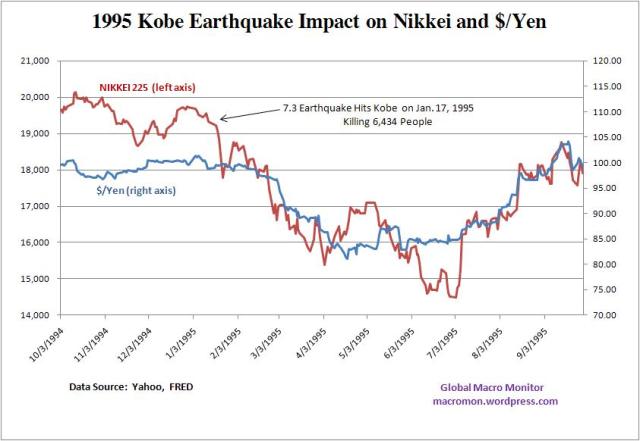

China's $2.8 trillion foreign-currency reserves will be of little help to recapitalize banks or prop up local governments, as these reserves would mostly be good in an external debt crisis, not a domestic one (among other things, trading in these reserves for yuan would cause the currency to appreciate sharply, damaging China's exports). And, for the record, the United States of the late 1920s also held

massive foreign-currency reserves, as did Japan in the late 1980s.

China's gold reserves will be of even less help, as they only amount to about

1.7 percent of the foreign-exchange reserves.

Inflation or Stagnation?

It's obvious the bust will have an impact on sectors beyond real estate and construction. Some

analysts even believe that China's GDP growth will drop to around 5 percent, i.e., half of its current level. Fitch Ratings and Oxford Economics recently did a study on what might happen if this came true. Among the main conclusions was a major economic slowdown in both developed and emerging economies in Asia, with GDP levels almost halving across the continent. The sectors most likely to suffer in China and elsewhere included steel, energy, and heavy manufacturing.

The report also predicts a 20 percent plunge in industrial-commodity prices following such a scenario, which would have serious implications for countries like Australia and Canada, both of which are heavily reliant on mining exports. This is of particular importance to Austrian investors and anyone else looking to such commodities and mining stocks as a hedge against looming American and European inflation.

In China, too, price inflation is a growing concern. The official number in late 2010 was 5 percent — a 28-month high. In reality, though, this number is likely to be far higher, as food prices alone jumped by an estimated

50 percent in Shanghai last year, even doubling in other parts of the country. Li Wei of Standard Chartered expects official price inflation to reach 8 percent just in the first half of this year, while Yu Song of Goldman Sachs expects it to go north of 10 percent.

In December last year the Politburo announced it would move from a "relatively loose" monetary policy to a more "prudent" one in 2011. Apart from destabilizing the economy, the government knows that high inflation can also trigger civil unrest. This was, for example, a root cause of the Tiananmen Square protests, where the official CPI jumped from 7.3 percent in 1987 to 18.5 percent in 1988, and then to 28 percent in early 1989. Then as now, there is growing unrest in China over soaring consumer prices, yet many people reluctantly accept it — just as long as the economic boom carries on.

Conclusion

China may very well become "Dubai times 1000," as Jim Chanos puts it, though the jury is still out on what the actual magnitude of the crash will be.

While the economic systems of China and precrisis America are certainly different, below the surface China is plagued by staggering levels of credit expansion, speculation, malinvestment, and toxic loans — much like what we saw in America. The notion that the iron-fisted Chinese government is in control of this situation is a dangerous one. The laws of economics are omnipresent and cannot be overridden simply by force. Trying to apply top-down central planning to an economy that is more and more driven by bottom-up market forces will inevitably have grave consequences. Wild credit expansion always leads to the same things: price inflation, malinvestment, and bubbles.