The end of the Fed's program of quantitative easing will bring plenty of bumps but won't crash the US economy. Emerging markets could be in for a rockier road.

What happens in June when the U.S. Federal Reserve stops buying $100 billion in U.S. Treasury notes every month as part of the program of quantitative easing know as QE2?

You've heard the wails of worry. Which buyers, if any, will pick up the slack when the Fed exits this market? At the least, U.S. interest rates will have to rise to attract those additional buyers. At the worst, a lack of buyers will tip over the entire tower of cards that is U.S. government finances.

And I'm starting to hear another, still-building cacophony of worry. The Fed's most recent program of bond buying will have put $600 billion into the U.S. money supply by the time it's over in June. A significant portion of that hasn't stayed in the United States. Instead, some of that money has gone overseas, seeking better returns in Brazil, China, Turkey and Indonesia than it can get in any domestic U.S. market.

What will happen, the emerging worry goes, when this hot money starts to flow out of the financial markets in Brazil, China, Turkey and Indonesia? Won't the flight of this hot money create another global financial crisis akin to the Asian currency crisis of 1997 that brought the world to the brink of a financial meltdown?

The key thing that both these scenarios have in common is that they envision a big blow-up -- that things will go wrong quickly and in a big way.

Actually, I think, the most likely scenarios have less in common with the

Hindenburg disaster than with a slow leak from an inflatable plastic model of the globe. In other words, the end of QE2 will bring not a bang of disaster but a whimper of pain. But investors still need to pay attention.

First worry: Who will buy our Treasurys?

Unless you've got some secret alternative global currency that investors, institutions and central banks can buy instead of the dollar, I don't think this question as dire as it seems.

The foundation of this worry is a belief that overseas investors have so many dollars already in their portfolios that they certainly won't buy more. At the moment, that does not seem to be the case. Foreign investors as a whole -- and this includes the world's central banks -- owned $4.45 trillion in Treasurys as of January 2011. That's up from $3.7 trillion in January 2010.

You may find this hard to fathom -- I know I've got trouble wrapping my mind around it. Given the size of the U.S. budget deficit, why would any sane investor buy U.S. government paper? The U.S. budget deficit for the fiscal year that ends in September is 10.5% of GDP. Greece, where 10-year bonds yield more than 13%, shocked investors when the 2010 budget deficit was revised upward to 10.5%. The yield on the 10-year Treasury is, in contrast, 3.41%.

But the United States is not Greece in some critical ways. First, Greece is saddled with the

euro, which is run by a distant central bank. The United States, in contrast, controls its own currency. Greece can't depreciate the euro to restore the competitiveness of its economy. Instead, restoring the profitability of the deeply uncompetitive Greek economy so the country can pay off its debt will require very painful long-term reductions in the pay that Greeks take home for their work. Frankly, I doubt that Greece can get there using that method. The country will have to restructure its debt, even though its

leaders are now insisting it has no intention of doing so.

The United States, on the other hand, can depreciate the dollar -- let the value of the dollar sink so that it can pay back what it owes in cheaper dollars. I know this possibility is often greeted with horror. The United States has no intention of paying back its debts, the criticism goes. It will just depreciate its way out of the current mess.

That is a problem, especially in the long run, if creditors decide that the United States lacks the intention or ability to pay its debts. Then the U.S. could see the same kind of buyers' strike that Greece, Portugal and Ireland have gone through -- but without the backup of buying from a central bank. There simply isn't a central bank in the world big enough to provide that support.

But a depreciating dollar that's combined with a reasonable budget deficit reduction plan is something else entirely. That's just business as usual: The world's bondholders recognize that the United States will have to let the dollar depreciate in order to reduce the U.S. balance-of-payments deficit with the rest of the world. An orderly reduction of that deficit because of a slipping dollar would, in fact, be a good thing in a world that can't keep running huge surpluses in some economies and a huge deficit in the United States.

Whether the world can engineer that kind of orderly rebalancing is an open question. Right now the odds aren't good. In fact, on April 18, Standard & Poor's lowered its outlook on U.S. debt to "

negative," citing concerns that policymakers would not be able to agree on how to address the country's fiscal problems. Stocks plunged in response.

Foreign money has nowhere else to go, for now

The biggest thing the U.S. Treasury market has going for it is the disarray in financial markets that might otherwise provide reasonable alternatives in the volume that global investors need. The euro is still in crisis, and the euro bloc of nations looks further away from a solution to the problem than it did six months ago. Japan's budget is even further out of balance than that of the United States -- the yen may be a great currency to borrow if you want to invest somewhere else, but Japanese government bonds are even less attractive than U.S. Treasurys in the long run. The Chinese yuan may be an alternative to the U.S. dollar someday, but not until the Chinese government decides that its currency is fully and freely convertible.

All this may explain why, despite saber-rattling about diversifying out of the dollar, foreign central banks bought 60% of the $66 billion in 10-year Treasury notes sold this year.

As long as U.S. inflation remains subdued -- and the data released on April 15 show U.S. core inflation (the number the Federal Reserve cares about) running at an annual 1.2% rate as of March, with headline inflation at an annual 2.7% -- I think the Treasury market will be able to absorb the end of the Federal Reserve's buying program. U.S. interest rates may move up slowly as the U.S. dollar falls -- if the euro crisis moderates so that the European Central Bank can continue to raise its benchmark interest rate.

The biggest chance of a "big bang" disaster will come not when the Fed stops buying but when, in order to fight inflation, the Fed needs to start selling the some of the assets that it piled on its balance sheet in QE1 ($1.3 trillion) and QE2 ($600 billion). Then investors will get to see how big the world's appetite for Treasurys truly is.

I think that challenge is a question for 2012 and not this year. And if you think what I'm saying is that the Federal Reserve will be able to kick its balance-sheet problem down the road for another year -- assuming that our politicians don't send the country into default in July in the battle over

raising the debt ceiling -- then you're exactly right.

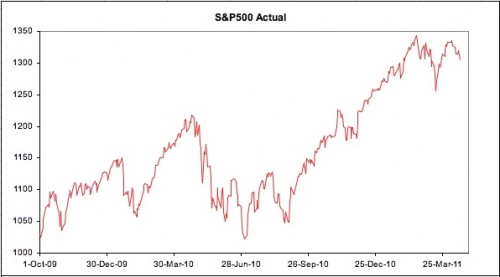

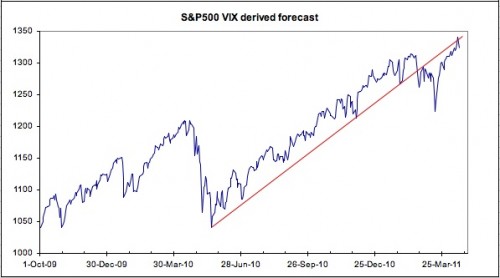

That doesn't mean the end of QE2 can't have some wicked, though less than disastrous, effects in 2011. Even a small increase in U.S. interest rates from the end of QE2 could significantly slow growth in the U.S. economy when it's added to higher oil prices and to the cuts made so far in federal and state government spending. Each of these measures is a small drag on growth in the economy. Together they're enough to produce a slowdown in U.S. growth that's noticeable, even if well short of a return to recession. Looking at the combined effect of all these factors on U.S. economic growth is one reason why I think the U.S. stock market won't do as well in the second half of 2011 as it will in the first half.

That's my take on worry No. 1. Now what about worry No. 2?

A good deal of the money that the Federal Reserve pumped into the U.S. financial markets through QE2 didn't stay in those markets. Instead, it went looking for better returns elsewhere in the world. Since the start of QE2 back in November through February 2011, about $58 billion of that money went into emerging financial markets, according to EPFR Global, a company that researches fund flows. Of that $58 billion, about $12 billion went into emerging market bonds and $46 billion into emerging market stocks. That flow of cash is one reason why emerging market stocks were up about 6% in 2011 as of March 31 and emerging market bonds were up 1%.

What happens when those cash flows reverse and this hot money starts to flow out of these emerging markets? The worst imaginings result in something like a replay of the

1997 Asian financial crisis, when outflows of hot money took down stock markets in countries that included Thailand and Indonesia, requiring major rescue efforts by the Federal Reserve and the International Monetary Fund to prevent a global financial market meltdown.

Less catastrophic scenarios merely call for an extended correction in emerging market stocks. Emerging market stocks recently traded at a 10% premium to developed market equities, Alain Bokobza of Société Générale calculated in the Financial Times on April 14. With the end of QE2, that could turn into a 15% to 20% discount by the end of 2011, he said. To buttress his argument, he notes that stocks in India trade at three times book value despite inflation well above 8% and with the prospect of more interest rate increases from the Reserve Bank of India.

I think investors can rule out a repeat of the 1997 Asian crisis. Then, the countries involved had built up debt loads that left them dependent on hot money. They didn't have the kind of foreign exchange reserves that emerging market countries do now. China's $3 trillion in foreign reserves is by far the largest fund, but Brazil, India and South Korea each come in near $300 billion. Even Thailand, a country that was at the locus of the crisis, now has reserves near $200 billion.

In 1997, when overseas hot money fled as asset bubbles in these countries burst, some emerging market countries, Thailand, for example, found themselves essentially bankrupt. I don't think recent asset bubbles are big enough to sink these countries' economies -- which are now much bigger and have better reserves. That doesn't mean, of course, that individual banks in these economies couldn't find themselves overexposed to bubbles in real estate and consumer loans.

The second-worst scenario, a 15% to 20% correction in emerging market stocks, is certainly possible. (And while I wouldn't enjoy that, please remember my Rule of Two -- that emerging markets are about twice as volatile as developed markets -- so a 20% drop in emerging market stocks is not a bear market, as it would be in the United States, but instead roughly equivalent to a 10% correction.)

I think this scenario is unlikely because it ignores the positive effects of the end of QE2 on emerging economies. An end to heavy flows of hot money would reduce the upward pressure on the currencies of these countries. That would give relief to exporters in economies such as Brazil that now say they are being priced out of global markets, and thus it would add to economic growth in these economies. It would also give these countries' central banks more room to fight inflation, thus bringing interest rate cycles to a quicker end. (Central banks in some countries have been reluctant to raise interest rates to fight inflation because higher rates would attract more hot money from overseas, pushing up the domestic currency even more and hurting national exporters.)

Reversing the flow of hot money out of emerging economies into the U.S. economy would also, quite possibly, strengthen the U.S. dollar. That in itself would lower global commodity inflation, since global commodities priced in dollars go up in price when the dollar falls.

But it's not clear to me how quickly these flows would reverse. About $15 billion, or one-third of the money that flowed into emerging market equities from the start of QE2 in November 2010 through February 2011, has flowed back out of these markets since then, according to EPFR Global. That's either a lot -- if you look at how fast it happened -- or not very much, considering the outperformance of the U.S. stock market in 2011.

And there is, of course, just the little question of how fast this money will flow out of these emerging markets if investors see slowing economies in Europe and the United States. But whichever way you look at it, that outflow hasn't tanked emerging market stocks.

I think the course of worry No. 2 depends on the timing of the inflation battle in emerging economies. The longer the fight drags on and the more growth that central banks need to take out of these economies, the more hot money will flow out of emerging stock markets.

That question will be answered on a market-by-market basis as investors see that the inflation/interest-rate/economic-growth story is very different for a Chile, a Brazil, a China or an India.

That's the reason that I've urged investors to be very selective when they allocate money to emerging markets now. To repeat, you want to put money into economies that are close to the end of their cycle of interest rate increases and to hold off on investing in countries where the length of the battle is still open.

At the time of publication, Jim Jubak did not own or control shares of any company mentioned in this column in his personal portfolio. The mutual fund he manages,

Jubak Global Equity Fund (

JUBAX), may or may not now own positions in any stock mentioned in this column. Find a full list of the stocks in the fund as of the end of March

here.