by Charles Hugh-Smith

I am privileged to present a comprehensive yet succinct two-part account of the banking/debt crisis in Cyprus, prepared by a knowledgeable resident of that nation. Why do the debt crisis in Cyprus and the subsequent "bail-in" confiscation of bank depositors' money matter? They matter for two reasons:

1. The banking/debt crisis in Cyprus shares many characteristics with other banking/debt crises.

2. The official Eurozone resolution of the crisis--the "bail-in" confiscation of 60% of bank depositors' cash in an involuntary exchange for shares in the bank (which are unlikely to have any future value)--may provide a template for future official resolutions of other banking/debt crises.

In other words, since the banking/debt crisis in Cyprus is hardly unique, we can anticipate the resolution (confiscation of deposits) may be applied elsewhere.

Readers may recall that the initial resolution in Cyprus called for all depositors to accept a "haircut" (the harmless-sounding vernacular for confiscation). This triggered widespread outrage, and was soon amended to exempt the first 100,000 euros on deposit. 60% of the remaining "uninsured" deposits would be confiscated and involuntarily exchanged for bank shares, in two tranches of 37.5% and 22.5%: Bank of Cyprus starts process of turning uninsured deposits into stocks (April 29, 2013)

In sum, it's extremely important to understand the real story of the Cyprus Debt Crisis to be able to sort out which features of the situation may be considered unique and which ones are shared by other banking/debt crises.

We are fortunate to have this on-the-ground account by a longtime resident of Cyprus, John H. Morgan. Here is Part 1 of his report.

The story of The Republic of Cyprus’ descent into bankruptcy is a Greek tragedy of epic proportions.

The Cyprus Political Crisis post-1974

In July 1974, in the face of an airborne invasion backed by the armour of NATO member Turkey, 200,000 Greek Cypriot citizens ran from their homes with only the clothes on their backs. The Greek Cypriot armour and infantry were no match for the second largest standing army in NATO, equal in size to the British and French forces combined. The Greek Cypriots were easily routed. The victors conducted summary executions of thousands of their prisoners and threw some of the bodies down wells to hide their crimes.

History, geography and economy of Cyprus (Wikipedia)

37% of the island of Cyprus was taken; 50,000 Turkish Cypriots fled north and took shelter in the homes abandoned by the Greek Cypriots; 200,000 Greek Cypriot refugees fled south and were housed in tents, in the same way that hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees are now sheltered by the Turkish Government in 2013.

Yet so began the housing boom in Cyprus. Refugees in the Turkish-occupied North had the pick of thousands of abandoned homes. Refugees in the South had to build their own. The Cyprus Government parcelled out plots of government land. The banks would not give mortgages on state land so the Cyprus Government stepped in and funded the construction industry.

Political opportunism was not far off. During his election campaign Former President Glafcos Clerides allegedly promised to give Greek Cypriot refugees temporary title to thousands of Turkish Cypriot homes and land. Once he was elected, the programme was halted. He handed out 8,000 Government jobs to party cronies in his 10 years as President, perhaps by way of consolation.

Patronage, cronyism and clientelism have been the hallmark of government control in both the South and occupied-North of Cyprus. Since the Turkish occupation, employment in the State sector in Cyprus has been used to reward party loyalty (and to incentivise elections). The civil service in the free Republic of Cyprus has grown from 18,000 workers in 1978 (costing €36 million in annual salaries and benefits), to 70,000 workers in 2012 (costing taxpayers and business €2.8 billion per year).

One in six workers out of a total workforce of 440,000 are employed in the public sector. The government controls an empire of 63 Semi-Government Organisations (SGOs) plus the Cyprus National Guard, an army of conscripts headed by a permanent officer corps. Officials in charge of the SGOs are appointed by party affiliation. SGOs are monopolies and can set their own tariffs.

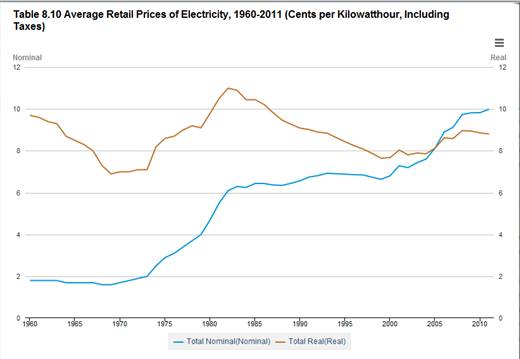

State teachers have become the highest paid in Europe, with top teachers earning almost three times (282%) the salaries of their counterparts across Europe. In January 2013, state teachers went on strike because they were required to work one extra lesson per week, 40 minutes. Electricity prices skyrocketed to the second highest in Europe, to fund the pensions of the broader state sector. Between 2009 and 2011, the price of domestic electricity doubled. A clerk in government with a High School Certificate could earn the same salary as a Professor in a private university.

In December 2012, the pension funds of the Telecommunications, Electricity and Ports Authorities were raided to pay State workers their 13th cheques. In May 2013, the workers of the Ports Authority downed tools because their 14th cheque was reduced by half.

All political parties have been complicit in the transfer of wealth from the private sector to the public sector. In 2009, 98 shipping containers of Iranian armaments on their way to Syria, were intercepted by the US Navy. On 11 July, 2011, they exploded while being stored at the Cyprus naval base. The island’s main power station was destroyed and 13 lives were lost. Insurance companies paid out the first claims within weeks. The Cypriot Parliament charged the taxpayers €99 million to cover claims for “Public Liability”. The item was slipped in as the last entry of the 2013 State Budget.

The DIKO Party is the government’s coalition partner (and coalition partner of most of the previous governments). While in power from 2003 to 2008, is alleged to have amassed €18 million of Party funds by endorsing a contract to buy two additional Airbus planes for the loss-making Cyprus Airways.

In 2007, the DIKO government asked parliament to approve the construction of a multi-billion Euro offshore floating Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminal. The gas was meant to be used to power the Vassilikos Power station (destroyed in July 2011, as mentioned above). Parliament questioned why such a massive construction was needed when a few storage tanks would suffice. The government failed to tell the nation that trillions of cubic feet of gas had been discovered offshore. Politicians had set up a front company to take a cut of the billions of Euros taxpayers would contribute to build the plant and to ensure they received an annual dividend from the profits of selling millions of cubic feet of LNG to Europe.

Government debt has been compounded because Cypriots generally avoid paying taxes. Indeed, there are only 52 tax inspectors in the whole country. In her report to Parliament in April 2013, the Auditor-General noted that Cypriots owed their government €1.6 billion in back-taxes and fines, enough to pay off all Eurobond debt due in 2013. She pointed out that failure to collect taxes meant that €300 million of State revenue had been irretrievably lost.

At the end of December 2012, ex-President Christofias vacated the rotating Presidency of the European Council. For 6 months work, he would receive an EU pension estimated at €10,000 per month, courtesy of European taxpayers. For his 17 years as an MP and 5 years as President of the Republic of Cyprus, he would receive a State pension of €22,000 per month, a brand new BMW limousine costing €43,000, a driver, a secretary and 15 body-guards, courtesy of Cypriot taxpayers.

Just one month before Cypriot Presidential elections of February 2013, the Trade Union-backed Communist regime of ex-President Christofias was assiduously appointing party apparatchiks to all key State posts, such as to the Central Bank of Cyprus and the newly-formed State Hydrocarbons Company (theoretically a private company). This guaranteed that the looting and pillage of the Cyprus economy could continue, long after President Christofias had left power.

**********************************************************

The Cyprus Banking Crisis

Corruption was also endemic in the Russian Federation after the fall of the Soviet Union. The chaotic privatisation during the Yeltsin years from 1992 to 1999, made a selected few Russians very wealthy. Many of the new Russian oligarchs wanted to safeguard their money and moved their operations to Cyprus. The country offered a low tax regime. Few questions were asked. The island became a favoured tourism and business destination. The debt overhang which had accrued from rebuilding the Cyprus economy became manageable. There was a plentiful supply of homes and offices, a legacy of rebuilding the devastated island.

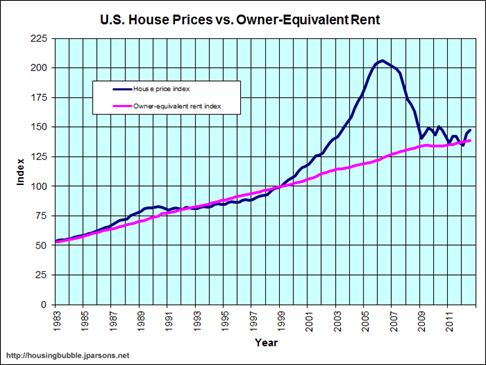

In 2004, the Republic of Cyprus joined the European Union. A new wave of investors brought great wealth to the island. House prices in the United Kingdom had been heavily inflated owing to short supply and easy credit. 60,000 Britons chose to buy affordable second homes or retirement homes in Cyprus. Between 2004 and 2007, fueled by a housing bubble, the Cyprus economy grew at 4% per year. At the end of 2007, the State Budget was showing a 3.5% surplus. Public debt was less than 60% of GDP. Cyprus qualified to join the Eurozone.

In 2006, attracted by the huge wealth deposited in Cyprus Banks by British and Russian investors, an innovative salesman managed to sell two insolvent Greek banks to the island’s second largest lender, Cyprus Popular Bank. He became chairman of the enlarged bank, which was named Marfin Popular Bank or Laiki Bank.

After Cyprus joined the European Monetary Union in January 2008, he was able to move €5.1 billion of Cyprus bank deposits to a company he set up in Athens. He used equity in his new company as collateral. This substantially weakened the balance sheet of Laiki Bank. €500 million was lent to a Greek Monastery to buy shares in his company. The Vatopedi monks swapped state land they laid claim to, for prime real estate in Athens. Greek politicians facilitated the deals in return for kick-backs. The scandal brought down the Greek government in 2009.

To cover their capital shortfalls, Cypriot banks invested in Greek Government Bonds which offered very high interest rates. Cypriot banks were also heavily exposed to the Greek property and commercial markets. When the local banks could no longer finance Cypriot Government spending, the Christofias government "borrowed" the €7 billion which had been built up by the Social Security Fund.

The Greek Government applied for a financial bailout in 2010. Cypriot banks held €5.3 billion of Greek Sovereign Debt and a total of €23 billion of Greek assets. Cypriot banks suffered heavy losses in the Greek financial meltdown. Laiki Bank alone endured a €2.4 billion write-down on the value of its Greek Government Bonds. The 80% “haircut” on bonds was proposed by German Chancellor Merkel and French President Sarkozy to make Greece’s debt burden manageable. Other losses by Cypriot banks were estimated at 25% of their total Greek loan book.

The country’s largest bank, Bank of Cyprus, had been affected by a €2 billion write-down of Greek Government Bonds during the Greek PSI, but its directors had made provisions. One of the provisions, used by both BoC and Laiki Bank, was to offer €1.8 billion of Contingent Convertible Bonds to the public. This was preceded by intense marketing.

Sixty thousand customers transferred funds from low-yielding deposits to take advantage of the promised high-yield bonds. In the end, their money was converted to worthless bank equity. The depositors claimed they had been tricked. There were public protests. When auditors reviewed the records of BoC during its subsequent restructuring, 28,000 computer files relating to the purchase of Greek Government Bonds had been deleted by special software.

The Cypriot Banks applied to the Central Bank of Cyprus for support. The state nationalised Laiki Bank and injected €1.8 billion (10% of GDP). The state was then shut out of the international bond markets.

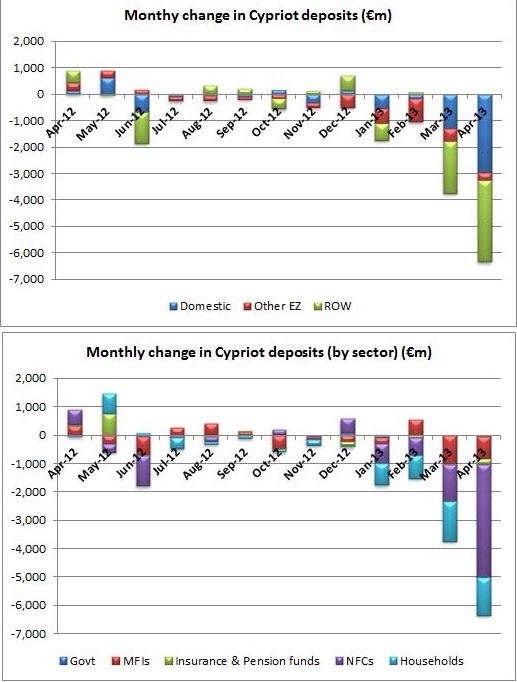

Laiki Bank was technically insolvent. There were rumours that the bank would default. Depositors had already withdrawn €3.3 billion of deposits by July 2012. The Central Bank of Cyprus propped up the ailing bank with billions of Euros of Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA).

In July 2012, the Christofias government turned to the rest of Europe for a bailout. President Christofias tried to dictate conditions to the Troika of lenders, the European Commission (EC), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Central Bank (ECB). He wished to avoid the political cost of signing the Memorandum of Understanding. This called for massive restructuring of the economy of Cyprus in return for a bailout. He had decided to pass the problem on to the next President.

Up until January 2013, a month before the Cypriot Presidential elections, German Finance Minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, denied aid to Cyprus by insisting that Cyprus did not qualify for European financial support. All the while, the Cypriot commercial banks were bleeding heavily in the Greek economic meltdown and were posting their best Greek assets as collateral for emergency funding from the Central Bank.

Furthermore, Schäuble told German voters, Cyprus should not receive German-guaranteed loans as it was an offshore tax haven and Germans would not want to risk their money to bail out wealthy Russians who had hidden their ill-gotten gains in Cyprus. (In a report commissioned by the Troika of lenders, European fraud agency Moneyval and Deloitte Financial of Italy reported a widespread lack of due-diligence, but could find little direct evidence to support such claims.)

Summary of Main Financial Report by Moneyval and Deloitte