by Attain Capital Management

The tendency of investors to jump on board with an investing thesis just before it turns sour is almost legendary. Attracted to the hottest investments like moths to a flame, they flutter in just in time to see the fire go out, and get stuck in a puddle of rapidly-cooling wax. Forgive us for stretching that metaphor, but you get the idea – chasing hot investments is as problematic as it is popular.

And when the boom in commodity prices in the early 2000s hit, it was no exception. Investor dollars lined up by the billions seeking commodity exposure, and financial engineers responded by providing a retail option for the masses – commodity ETFs.

The idea behind them was simple. Take some of your stock exposure and diversify it into another asset class, one which has been going up like crazy and feeds into the fear/excitement/confusion over the growth of China. Investors were asking, “where do I sign up?”

Have commodity ETFs been the diversifier people were looking for? Has that China thesis played out? Has an allocation to commodities helped portfolio performance? Not by a long shot… Most commodity ETFs continue to have three big problems: high volatility, -50% to -90% down moves, and a built-in performance drag from the so called negative roll yield.

What Goes Up…

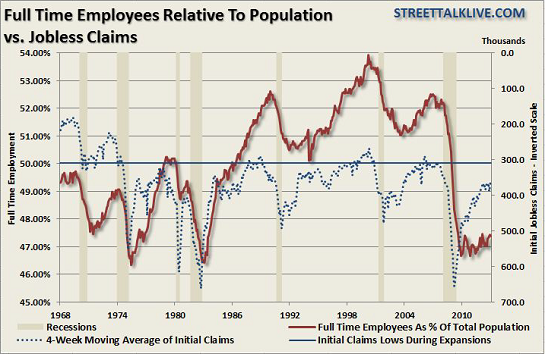

But first, back to the beginning. The dot-com crash didn’t just cap off the ‘90’s with a gut-punch to most portfolios – it also sparked investor demand for some true diversification – alternatives exposure. As usual, investors waited until after they had experienced the worst of the downturn in stocks before starting to look for something that wouldn’t be plummeting at the same time as their equity allocation. And taking a look around from 2002 to mid-2008, commodity prices were running up like mad.

Source: Dow Jones-UBS Commodity Index Total Return Index. Disclaimer: past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

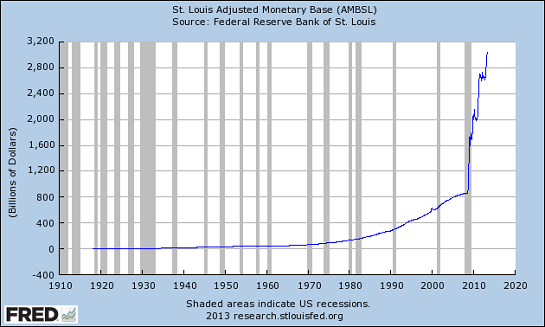

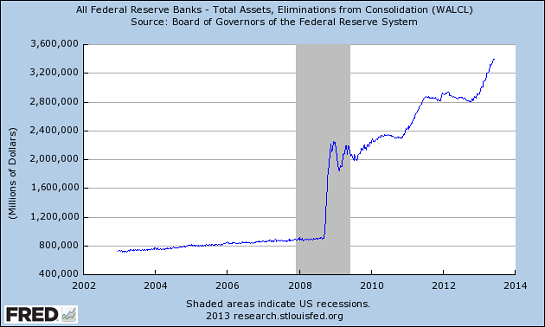

It wasn’t long before the trend had generated its own buzzword – the “Commodity Supercycle.” The thesis was that we were on the cusp of a huge run up in commodity prices. Jim Rogers and others like him trumpeted the praises of long-only commodity investments to anyone who would listen (and, in his case at least, continues to trumpet). Commodities had much higher to go, they said. Resource-hungry China and the rest of the developing world were going to send demand for raw materials soaring. After the financial crisis hit and central banks the world over responded with monetary easing, the “commodities must go higher” crowd had another argument in their arsenal – that rampant inflation would soon send commodity prices even higher.

And with so much demand for these products, companies were falling over each other to launch new commodity ETFs. Today there are hundreds to choose from, including single market funds, sector funds, broad commodity index funds, leveraged and inverse leveraged funds… And in the space of a few years, they have amassed huge sums of capital – currently nearly $140 billion is invested in commodity ETFs.

Must Come Down…

And then… Oops. Talk about bad timing. From 2008-present, commodities have been in one seriously ugly bear market. (And this is why we say long-only isn’t such a good idea after all).

Source: Dow Jones-UBS Commodity Index Total Return Index. Disclaimer: past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

The Dow Jones-UBS Commodity Index Total Return Index lost -42% from the ’08 peak. For individual markets, it was even worse. Oil futures lost nearly -77% from peak to valley, and remain more than -36% below the ’08 peak. Natural gas futures lost -86% from peak to valley, and are still down more than -70% from the peak. Not a ringing endorsement for the long commodities crowd.

And that’s to say nothing of the volatility. Think the stock market is prone to whipsaw behavior? Individual commodity markets saw much larger price swings than stock investors may be used to.

There’s a reason that regulations require we say futures investments come with substantial risk and aren’t for everyone.

Of course, the losses weren’t uniform – gold and silver, for example, seemed immune to gravity for quite a while, continuing to climb well into 2011. But “trees don’t grow to the sky,” as they say – and even the precious metals commodities have shown their true colors the last two years, with gold down –-27% from its high and Silver down –55%!

The “Supercycle” thesis is looking busted, with the legendary Stanley Druckenmiller even weighing in recently saying the commodities decline is just beginning. Perhaps the “Buy and Hold” approach in the world of commodities is better suited by another name: “Long and Wrong.”

Roll Yields, Contango, and Backwardation

But being on the wrong side of the trade isn’t the only problem with commodity ETFs. They can also suffer from a what is called negative roll yield due to the way they gain access to the markets they aim to track: via futures contracts. Futures contracts are finite in time, with traders buying the June 2013 Crude Oil contract, or the December 2013 Corn contract, and so on.

A simplified example: If you are long (having bought in hopes of prices rising) June 2013 Crude Oil futures, for example, and want to remain long after the end of June, you have to actually exit the June contract, and enter (buy) a new contract (say July). If you want to remain long at the end of July, you exit and enter August, and so on.

A long-term commodity investor must navigate the shifting landscape that this system creates – and for passive ETF investors, that means potentially experiencing a negative roll yield when markets are in Contango. As we explained in a newsletter from a few years ago:

“Contango is little more than a fancy word for explaining a futures contract curve where the further out contract months are more expensive than the front month contract months. It’s easier to understand using an example. Take Crude Oil futures. If the contract for January delivery is at $60, February delivery at $62.50, March delivery at $65, and December delivery at $75 – the further out the delivery, the more expensive the contract value. This is known as Contango, and reflects a view that future prices will be higher than current prices. Assuming a growing population, growing economies, and limited supply of commodities, there is research which shows the natural state for commodity pricing is Contango. The opposite, when current prices are more expensive than future prices, is called backwardation. That can occur when there is a supply issue such as when Hurricane Katrina shut in all of the Gulf of Mexico oil production.

Why does Contango pose an issue for commodity ETFs? Because these ETFs buy the nearer month futures contracts so that their share price tracks what is going on in the most actively traded contract, and must roll their positions to the further out months when the contracts expire (remember that a futures contract has a finite lifespan, with the February 2010 contract ceasing to exist on January 22nd, 2010; for example). The difference between the nearer month price and further out month price when they roll is called the roll yield. In a Contango market, the roll yield is negative because the roll results in selling the cheaper contract and buying the more expensive one. In our example above, if rolling from February to March Crude Oil futures, you would sell the Feb at $62.50, and buy the March at $65, resulting in a negative roll yield of -$2.50.”

It’s important to remember that the roll yield will not necessarily be negative – backwardation can result in a positive roll yield, too. But after 2008, falling prices and that negative roll yield created a double whammy where the ETFs were losing on both the direction of the trade, and the trade structure.

The Ugly Truth

Between falling prices and a negative roll yield, the results have not been pretty. The commodity ETF world has contained some of the worst investments around in the last few years. In fact, just over a year ago UNG was dubbed the worst ETF ever . It’s not hard to understand why – at one point it had lost more than 96% of its value since inception.

Disclaimer: past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

The ETF never traded at $500, of course. The above chart is adjusted to reflect the fact that the ETF has undergone two reverse splits: a 1-for-2 reverse split and a 1-for-4 reverse split.

But it’s not just UNG which has struggled. Other commodity ETFs and ETNs have been just as bad in tracking the price appreciation/depreciation they were designed to track. CORN, USO, JJC, JO, WEAT – they’ve all underperformed a simple strategy of buying the December futures contract and rolling it annually.

How much underperformance are we talking about? We charted the composite of several ETFs/ETNs for various markets against the simple roll annually strategy for those markets – averaging their performance once they came online – and did the same for simply buying and rolling the December contract each year. We ignored GLD and SLV as they don’t use futures contracts for their exposure, they hold the actual commodity in a vault. But for those using futures markets for their exposure – it isn’t pretty - read ‘em and weep below:

Disclaimer: past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. These results are hypothetical in nature and are intended for educational purposes only. Please read carefully the disclaimer regarding hypothetical performance below.

USO - Apr ’06, UNG - Apr ’07, JJC - Oct ’07, JO - July ‘08, CORN - Jun ’10, WEAT - Sep ‘11

Those drags on performance add up, amounting to a -40% lag for the ETFs in our hypothetical composites. That’s not 4 basis points, or even 40, or even 400 – we’re talking massive tracking error. How can so much money still be in these investments – especially when they are highly liquid and so easily ditched? Are futures markets really that scary and confusing that billions of dollars would rather sacrifice 40% in returns for the ease of an ETF? Maybe it is a bunch of ill conceived mandates for a certain percentage of portfolios to be in commodities? Whatever the reasons – we don’t get it.

ETFs Fighting Back

But the problems of the roll yield are no secret – investors (and the ETF providers, no doubt) have known about the cost of roll yield for years. Indeed, prop traders and even our old friend Emil Van Essen has used the knowledge of large funds rolling out of the near month contract and into the further out contract to inform their trades.

But some of these commodity ETF folks aren’t as dumb as they look, taking steps over the last year or so to address the problem – we covered some of their efforts in a recent blog post. These new ETFs are getting their commodity exposure by investing in a blend of futures contracts for varying maturity dates. For example, the Teucrium Corn ETF tries to minimize the problem by not just plowing into the front month contract for the market they track. Instead, they use the following futures contracts: (1) the second-to-expire Futures Contract for corn traded on the Chicago Board of Trade (“CBOT”), weighted 35%, (2) the third-to-expire CBOT corn Futures Contract, weighted 30%, and (3) the CBOT corn Futures Contract expiring in the December following the expiration month of the third-to-expire contract, weighted 35%. This dynamic, multi-month roll process is their attempt to reduce the impact of Contango markets eating into profits (or compounding losses).

And then there are others that avoid the problem of negative roll yield by simply avoiding futures contracts altogether. GLD, for instance, buys actual gold and keeps the bars in a vault to back shares of the ETF purchased by investors. The ETF tracks the spot price of the metal far better than those who rely on futures contracts, though GLD still faces that long-only problem (especially lately). However, even this approach isn’t without its drawbacks, as precious metals ETFs are taxed as “collectibles” in the same way as if you actually held the bullion. That means a top rate of 28% for long-term gains and 35% for short-term gains, rather than the more favorable 15% usually reserved for investment income.

So what’s an investor interested in more than just Gold exposure supposed to do? Just ignore so called “in the ground commodities” like Corn, Wheat, Oil, or even Sugar? We obviously wouldn’t advise that, but for retail investors who’ve been burned by the commodity ETF market, we wouldn’t be surprised to see that reaction.

And for big institutional investors (pensions, endowments, etc) with a mandate for a certain percentage exposure to commodity markets, ignoring the commodity space isn’t even possible. In our view, a forced mandate on a portfolio is a little like telling an NFL team 5% of their team has to be from the University of Delaware. What if the coach doesn’t like any of those players? What if they are slow? Too bad – play them or else.

So if these ETFs aren’t delivering, where can they turn? We’re clearly biased, but we happen to know an asset class which just happens to specialize in futures markets: Managed Futures anyone…

Managed Futures = Tactical Commodity Exposure

For us, the answer lies in tactical commodity exposure via managed futures programs. Tactical? Yes, tactical as in – being able to go both long and short (able to make money if commodities go up or down). We understand the desire to have exposure to markets like Corn, Oil, Sugar, and more. They could act as an inflation hedge. They could rally from fundamental factors like drought or a war in the Middle East. They are easy to understand. And they provide true diversification to a portfolio in that their price isn’t a function of future cash flows like a stock or bond.

What we don’t get is accessing commodities via a vehicle which requires that prices go up for you to make money in the commodities space. We’ve shown some of the massive down moves in commodity markets in just the past few years – and that’s nothing new. Commodity markets will always have violent swings to the downside. The whole world is basically setup to make stock markets generally point up (the Fed, 401ks, tax structure, etc), but there’s not similar structures in place to make sure we don’t grow too much Corn or pump too much Oil (well, besides OPEC). Why ignore the very real downside of commodities?

Managed futures access commodities a different way, being able to go long and short (ability to make money when prices fall) commodity markets. There are a million and one ways actual managed futures managers attempt to do this. Some use purely systematic methods such as selling when prices fall below a moving average, others are so called fundamental traders who rely on their experience and reading of the supply and demand picture to inform their investments on whether to bet on prices rising or falling.

Focus on Ag Traders

Now, it is true that most managed futures programs don’t just access in the ground commodity markets, or Agricultures (Ags) as managed futures calls them; they also access financial futures in markets such as stock, bond, and currency futures. And perhaps that scares away many investors from using managed futures for their commodities exposure.

But just like a logic puzzle saying all humans are mammals, but not all mammals are human - just because all of the big, well known managed futures programs don’t do pure commodity exposure doesn’t mean all managed futures programs don’t specialize in commodities.

Indeed, a select subset of the managed futures space called “Ag Traders” does specialize in commodities, and we’ve highlighted in the past how and what they do in a strategy spotlight. So just how do these commodity traders and their unique method of providing access to commodity markets compare performance-wise with the long-only commodity ETFs? We’re glad you asked.

We put together a composite of four of the top ranked Ag programs using our proprietary ranking system, and compiled the performance using the same method as for our ETF and Futures composites above – averaging the performance from when the programs came online. Now, there’s definitely some survivorship and selection bias going on here, but these are the programs we’ve been “selecting” for Ag exposure for our clients.

Disclaimer: past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. These results are hypothetical in nature and are intended for educational purposes only. Please read carefully the disclaimer regarding hypothetical performance below.

Shoot us an email at invest@attaincapital.com, and we’ll send you a full portfolio report on the above composite - including monthly gains/losses, all the risk/reward stats, correlations, and names of the component programs.

Three Strikes and You’re Out

The passive investing argument for ETFs is usually a good one – where you can get lower cost exposure without some fund manager screwing things up. And while we might agree that the passive ETF approach can be a good vehicle when compared with buy-and-hold equity mutual funds, the passive investment thesis breaks down in our opinion when applied to commodities.

For one – you have the very real negative roll yield problem. Two, you have the amped up volatility which can be associated with commodity markets. Is that really what you want as a diversifier in your portfolio – something more volatile than stocks? And most importantly, the third point is you have the massive drawdowns that are relatively commonplace in commodity markets. Coffee has fallen -58%, Sugar down -52%, and Cotton has dropped -60%... all within the last two years. Is the somewhat-iffy idea of commodities as an inflation hedge worth these large periodic losses?

We used to make fun of buy and hold stock folks as buy, hold, and hope. But buying and holding in commodity markets is even worse, becoming buy, hold, hope, and pay (the higher risk and negative roll yield).

It sure seems that a smarter way of accessing commodity markets and putting commodity exposure into your portfolio would be a tactical approach, where you enlist professional commodity traders to give you exposure to both the ups and downs of commodity markets.

See the original article >>