| A Wal-Mart detour

Ruminations on risk

How risky are emerging markets?

Being selective Asia Confidential has received a lot of feedback on our view of the relative attractiveness of Chinese and South Korean stocks in both Asian and international contexts. Some of the feedback has suggested that the risks with these markets are too great to make them investible at this juncture. This post is an attempt to address the issue through a deep dive into the concept of risk and how it relates to emerging markets. Risk is a topic little understood by the average investor and largely misunderstood by the financial industry. As a general rule, investors who want above-average investment returns usually have to be prepared to take on above-average risks. If investors have a low tolerance for risk then they shouldn’t expect anything but low returns. Put another way, war, catastrophe and the like imply high perceived risk and are normally associated with low stock market valuations, which infer the potential for higher long-term returns. Conversely, when things are going swimmingly, stocks are normally priced as such and high prices usually infer lower future returns. It’s explains why many quantitative studies have shown that high quality stocks under-perform low quality ones. It’s why strong GDP growth has little correlation to future stock market performance. It’s also why emerging markets are in the dumps, albeit having perked up over the past few weeks. Emerging markets are being deemed higher risk and are therefore sporting lower valuations to take this risk into account. Of course, the ultimate trick is to find markets and/or stocks where there’s a mismatch between risk and price. Where too much risk is reflected in current prices. That’s the secret sauce to investing and I hope to provide some insight on it in the current emerging market environment. A Wal-Mart detour

Let’s first take a bit of a detour via an article from a blog called Philosophical Economics. It’s excellent and well worth your time. It looks at Wal-Mart on October 3, 1974. Why this date? Well, it’s then that the S&P 500 bottomed after a bloodcurdling bear market during 1973-1974. At the bottom, the S&P trailing price-to-earnings ratio (PER) was 6.9x, the 10-year treasury bond yielded 7.9% and the Fed Funds Rate was 10%. Wal-Mart at the time was a smallish, southern retailer with stock price of $12 and a trailing PER of 12.9x. In other words, it was priced at about a 90% premium to the market. On a relative basis, it looked expensive. It didn’t turn out to be so expensive. From the 1973 bottom, the S&P 500 has since returned 12% per year. Not too shabby. However, Wal-Mart has returned 23% per year over same period. A US$10,000 investment in Wal-Mart shares then would now be worth roughly US$45 million. If you’d managed to make such an investment, and I’m not sure anyone outside of the Walton family has, then my guess is that you probably wouldn’t feel a pressing need to actually attend a Wal-Mart store any time soon! How could Wal-Mart have obliterated the returns of the S&P 500 when it was priced at almost double the valuation in 1974? Obviously, the company turned out to be an outstanding retailer. Yet the stock also turned out to be cheap relative to its growth prospects. What would the appropriate price have been for Wal-Mart to achieve returns in line with the index since that time? It turns out a stock price of $600, or about 50x higher, with a PER closer to 600x! The article’s concludes thus: “Now, my goal here isn’t to question the merits of a systematic value-based investment strategy. Markets put a high risk-premium on businesses that have run up on hard times. The risk-premium statistically overcompensates for the inevitable failures that occur in the lot, and therefore a disciplined strategy of harvesting the risk-premium will tend to outperform over time. But if we’re going to get into the nitty-gritty of active stock picking, if we’re going to delve into the details of the individual names themselves, we shouldn’t blindly conclude that low multiples offer buying opportunities, or that high multiples imply froth or danger. The truth is sometimes the other way around.” There are lots of good points here. But I’d like to elaborate on the risks involved with the Wal-Mart trade at that time. The 1974 market bottom was reached after a near 50% decline from the peak of 20 months earlier. The country was deep in recession. Two months before the market bottom, the US President Richard Nixon resigned in disgrace over the Watergate scandal. About a year earlier, there was the famous oil crisis. And don’t forgot that the US was then still involved in the Vietnam War. Therefore when the market bottomed, it was a tremendously turbulent period. To invest in the market or Wal-Mart at the time, even at low valuations, would have required extraordinary discipline. Very, very few had the capacity to stomach the risk (a then little known investor by the name of Warren Buffett did have such capacity. Though he didn’t purchase Wal-Mart, he made other now famous trades, including that of the Washington Post). Which brings me to a further point on risks associated with the Wal-Mart trade. To get comfortable investing in Wal-Mart itself in 1974, you’d have had to know a lot about the business, management and retail sector – including the potential for big box retailers. You’d have had to make a careful assessment of all of these and their associated risks to be willing to pay a 90% premium for the stock versus the market. And, of course, you’d have needed the patience to hold the shares for the next 40 years to reap the rewards. This discussion has only included the known risks though. We hasn’t even explored the unknown risks, harking back to the “known unknowns” jargon of Donald Rumsfeld. Ruminations on risk

In the investment world, risk can be simply defined as the possible loss of capital. And there are really two forms of risk: short-term and long-term. Short-term risk is the short-term volatility in prices. This risk is usually measured by standard deviation. In layman’s terms, by buying Wal-Mart in 1974, you’d have had short-term risk of the stock dropping by 50%. If that happened though and you didn’t sell, the loss would have only been on paper and temporary. Long-term risk is the potential for the permanent loss of capital. Permanent meaning an inflation-adjusted loss over a +20 year period. One which you normally can’t recover from. This kind of loss is usually precipitated by certain events (unlike the losses associated with short-term risk). For instance, war and confiscation of assets can represent permanent loss. It happened to Germany post-World War One and Two. It happened to revolutionary Russia and China. You can also experience deflation a la Japan. This doesn’t happen often but when it does, look out. From peak to trough, Japanese stocks went down about 80% and real estate land values by closer to 90%. A more common event in recent history has been inflation. In Germany during the 1920s, hyperinflation resulted in cash and bonds being worthless. That’s one of many instances of serious inflation/hyperinflation throughout history and represents real, permanent capital loss. Typically you won’t be able to forecast long-term risk. Therefore it represents unknown risk. This is important when people cite examples of stock market successes such as Wal-Mart. The US hasn’t experienced most of the events associated with long-term risk. It’s been involved in wars as the victor not the vanquished. It’s had serious inflation, but not hyperinflation. It had regular deflation during the 19th century, but not since. And it’s only had few instances of confiscation. In short, stockbrokers love to promote the US and its companies and show how investors could have made millions by buying and holding stocks in the long-term. They don’t talk about the paltry returns of still successful countries such as Germany, Japan and so forth over the past century. How risky are emerging markets?

Now circling back to emerging markets, these markets appear cheap compared to their own history and compared to other regions. Currently emerging markets trade at 1.4x price-to-book (P/B). That’s near the depths of the Lehman panic in 2008.

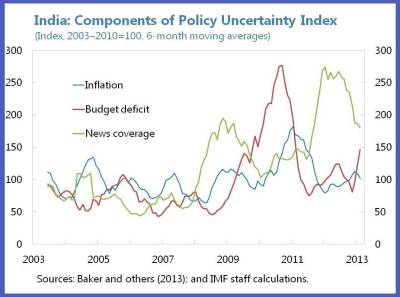

Valuations of emerging markets compare favourably to those of the developed world. For example, the S&P 500 trades at 2.7x P/B, or close to a 50% premium. Within Asia, some markets are trading much cheaper than the emerging markets average valuation. South Korea trades at close to book value. The China A-share market is at 1.4x P/B, or in line with the average. However, China H-shares (those listed in Hong Kong) trade at 1.1x. An alternative method of looking at valuation is via PERs. Both China and South Korea have forward PERs of 8x. This effectively means both offer more than 12% pre-tax earnings yields (100 divided by 8). That compares very favourably to long-term bond yields in both countries. The question is: why are these emerging markets seemingly cheap? And the answer goes back to our introduction: they’re perceived as high-risk investments. As for the risks, there are many. For emerging markets in general, QE tapering is front and centre. Funds which flowed from the developed world to emerging markets are now reversing (the latter had offered higher yields versus the former and that is now turning around). In a more volatile environment, the Ukraine fall-out has heightened emerging market risks from an investment point of view. This doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, but it’s just creating further uncertainty in an uncertain world. The final key factor is the prospect of a China credit bust. Such an event would hurt commodities, of which China has been the central demand driver. And emerging markets have high exposure to these commodities. Turning to the risks associated with individual emerging markets, let’s take a look at South Korea. Short-term risks here include: - A developed world slowdown hurting its large export market.

- Further yen depreciation impacting its exports too.

- A messy rebalancing away from dependency on manufacturing towards consumption.

- High household debt and related credit issues.

The long-term risks would probably centre on one particular risk: North Korea and the possibility of war, perhaps nuclear war. This is a known risk that could also possibly be classified as a short-term risk. How about the granddaddy of emerging markets, China? This market’s short-term risks have been well documented by this newsletter and include: - The unraveling of a mammoth credit upturn.

- Structurally lower growth as the economy shifts from being investment-led to consumer-led.

- A developed world slowdown hurting its large export market.

- Prospect for further yuan depreciation in a bid to prop up its exporters.

The list could go on, but these are the main short-term risks. As for the long-term risks, the primary one would have to be the disintegration of the Communist Party, via revolution or otherwise. There are many other long-term risks which we won’t go into here. Being selective

Asia Confidential has advocated China and South Korea as offering the prospect of above-average long-term returns. That doesn’t mean every investor ought to go out and buy them though. If you have low risk tolerance, then these possible opportunities may not be for you. Put another way, these markets may seem cheap but could get a lot cheaper, as a result of any of the aforementioned short-term risks. The ability to hang in for the long haul depends on your risk tolerance. If you think that you have the capacity to take on such risk, then there’s also the opportunity to do some homework of your own on these emerging markets. For example, when it comes to China, investing in a market ETF is the simplest way to do it. But it may not be the best way. Something to consider is that banks have large weightings in the China market. They account for about a third of the H-share index. If you buy an H-share ETF, you’re buying large exposure to the Chinese banks. These banks are at the heart of the unwinding of the credit bubble. The largest banks are state-owned and were central players in loans to state-owned businesses during China’s notorious 2009 stimulus. Much of the credit flowed through to the massive infrastructure projects which have since attracted so much attention (ghost cities and so on). The China banks have extraordinarily cheap valuations, on the surface. Most are priced below book value and with forward PERs of less than 5x. The reason for the low prices is that the market thinks they are risky investments. More specifically, that they have dodgy loans on their books, many of which are likely to turn bad. It’s very difficult to make an investment case for these banks. Yes, they’re pricing in non-performing loan ratios (NPLs) of 7-8%, which is at the high end suffered by banks in recent financial crises. However, it’s impossible for outsiders to determine what the ultimate figure will be. In banking parlance, it’s impossible to know the quality of the loan book. If you can’t determine the quality of the loan book and the future earnings power of these banks, it’s also difficult to get a sense of the proper pricing for the stocks. Without a sense of this, you’re investing on faith and little else. In the view of Asia Confidential, the opportunities in China are likely selective and lay outside of the banks. I’ve mentioned cheaper internet names, insurance and consumer discretionary stocks as areas exposed to the “new”, consumption-driven China, which may be worth exploring. It’s in these areas where there may be a mismatch between risk and price. Tying all of this back to the notion of long-term risks mentioned earlier, it’s impossible to foresee these risks in China or anywhere else. One course of protection is to have a diversified investment portfolio. In other words, whether buying equities or more specifically, emerging market equities, it’s best not to bet the ranch on them. AC Speed Read - Some feedback to recent posts suggests emerging markets are too risky to be investible at this point. - Risk comes in two forms: short-term and long-term. Short-term risk involves short-term price volatility while long-term risk is the potential for permanent loss of capital. - Emerging markets hold both risks, but the question is whether these risks are accurately reflected in prices. - We think in select markets such as China and South Korea that there’s a possible mismatch between risks and prices, providing some potential opportunities. That’s all for this week. Thank you for taking the time to read this post. |

Risk Management in Trading: Techniques to Drive Profitability of Hedge Funds and Trading Desks: Davis Edwards: Libri in altre lingue

Risk Management in Trading: Techniques to Drive Profitability of Hedge Funds and Trading Desks: Davis Edwards: Libri in altre lingue