by Kimble Charting Solutions

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Could The Upcoming USDA Report Hold Some Surprises?

By: Kevin Van Trump

Etichette:

articles,

commodity,

commodity article,

market articles

Percentage of Oversold Stocks Exceeds 50%

by Bespoke Investment Group

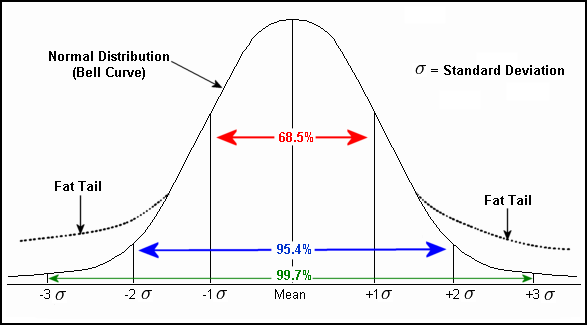

Each morning in our Morning Lineup report for Bespoke Premium clients, we provide an update of the percentage of stocks in the S&P 500 that are overbought and oversold. Stocks are considered to be overbought whenever they are trading more than one standard deviation above their 50-day moving average, and they're oversold whenever they are one standard deviation below their 50-day.

Yesterday, the percentage of stocks that are currently oversold exceeded 50% for the first time since March 16th. As shown in the chart below, over the last year, prior spikes where the percentage of oversold stocks exceeded 50% led to at least short term rallies in the S&P 500. After five straight weeks of losses, bulls are hoping that history repeats itself.

Etichette:

Analysis Technic,

articles,

Index,

market articles

Gold, Silver and Crude Oil Commodity Charts Elliott Wave Update

By: Tony_Caldaro

Gold has reached another interesting juncture. While Silver tanked over 30% in May Gold held its’ own with only a 6% decline. Then after making that low in early May Gold started to rally again, and is now in another confirmed uptrend. The question now arises; Is this a B wave rally in an ongoing Major wave 4, or is Minor wave 5 now extending in this extended Major wave 3?

OEW analysis of this entire 10 year bull market suggests the latter. That Minor wave 5 is now extending. This analysis suggests the April uptrend high was Minute wave i of Minor wave 5, and the May low was only Minute wave ii. Should this count be correct Minute wave iii of Minor 5 should be underway now. And, our $1700-2200 target for Major wave 3 is still a possibility.

The more obvious count would suggest this is an Intermediate B wave rally within an ongoing, and more complex , Major wave 4 correction. Currently we are displaying this count as the primary count on the Gold charts, with the extension of Minor wave 5 as the alternate count. Should Gold break out to new all time highs the Minor wave 5 count would gain in probability.

Recently Silver’s charts, oddly enough, look more like the Crude oil charts than Gold. We’re still expecting both to complete their corrections within the light blue band posted on their daily chart.

Etichette:

Analysis Technic,

analysis technic article,

articles,

crude oil,

energy,

gold,

market articles,

metals,

oil,

silver

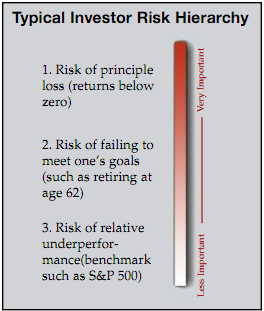

MODERN PORTFOLIO THEORY IS HARMING YOUR PORTFOLIO

By JJ Abodeely

In the paper Vincent argues that the flawed foundation of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) that risk=volatility has allowed MPT advocates to control the language of the debate and set the stage for the obvious conclusion that passive index-based investing is inherently superior. And don’t think for a second that this debate is simply theoretical, academic, or unimportant– the basic tenets of MPT shape the decisions of nearly every institutional money manager, wealth management firm, investment counselor/consultant, and financial planner in profound and often disturbing ways. YOUR money is almost certainly being managed with these ideas at the core. The traditional approach to asset allocation is built on false axioms.

While Vincent’s direct assault seems to be focused on highlighting the mistreatment of active, concentrated equity or fixed income asset managers vs. holding a passive equity or fixed income index, his arguments hold sway over the much larger and dangerous consequences of MPT on asset allocation. My assertion is that most damage to investors portfolios from the traditional approach to investing comes from the foundation of static, backward looking assumptions informing broad asset allocation decisions.

Vincent’s Case

In the piece, the author does a fantastic job of summarizing the history of Modern Portfolio Theory and it’s building block components:

- Harry Markowitz’s work on “Portfolio Selection” (which informs the chart above) proved mathematically that diversification could reduce volatility which he equated with risk

- William Sharpe’s Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) which mathematically defines an asset’s return into two parts:

- systemic risk or “beta” which describes how an asset has historically behaved relative to “the market” or a broad index

- idiosyncratic (stock specific) risk which can and should be diversified away

- Eugene Fama’s Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) which asserts that the market is ultimately efficient at pricing all available information

Vincent notes that most advocates for passive investing and MPT start with a compelling statement:

Active managers in general have been shown to underperform passive funds, especially when taking into account their higher management fees, taxes, sales charges, and trading costs. If you can make more money in index funds then why bother with the hassle of trying to find a good manager?

On the surface, that’s hard to argue with. I’ve seen studies that indicate after taxes, 80% of active long-only equity managers underperform their benchmarks over long time periods. Here’s the problem: Most “active” managers aren’t active at all. They are closet indexers:

While diversification has always been a selling point for actively managed mutual funds, the average number of holdings in a fund have increased dramatically since MPT made the scene. The average number of stocks held in actively managed funds is up roughly one hundred percent since 1980… the average fund holdings had risen to approximately 140 positions by 2000. The actual number of holdings in a given year could easily surpass 200 because portfolio turnover exceeds 100 percent per year on average…Investors in actively managed funds suffer – they receive quasi-active management at full active management prices.

MPT and the quantification of investing has further (mis)informed the debate by seeking a easy way to label and quantify “risk.” In 1952, Harry Markowitz chose variance or volatility of prices or returns to define risk. He did so because it was mathematically elegant and computationally simple. However, this idea has serious limitations (most of which Markowitz has since acknowledged).

On the individual stock level, Vincent notes

Risk is often in the eye of the beholder. While “quants” (who rely heavily on MPT) might view a stock that has fallen in value by 50 percent over a short period of time as quite risky (i.e. it has a high beta), others might view the investment as extremely safe, offering an almost guaranteed return. Perhaps the stock trades well below the cash on its books and the company is likely to generate cash going forward. This latter group of investors might even view volatility as a positive; not something that they need to be paid more to accept. On the other hand, a stock that has climbed slowly and steadily for years and accordingly has a relatively low beta might sell at an astronomical multiple to revenue or earnings. A risk-averse, beta-focused investor is happy to add the stock to his diversified portfolio, while demanding relatively small expected upside, because of the stock’s consistent track record and low volatility. But a fundamentally-inclined investor might consider the stock a high risk investment, even in a diversified portfolio, due to its valuation. There’s a tradeoff between risk and return, but volatility and return shouldn’t necessarily have this same relationship.

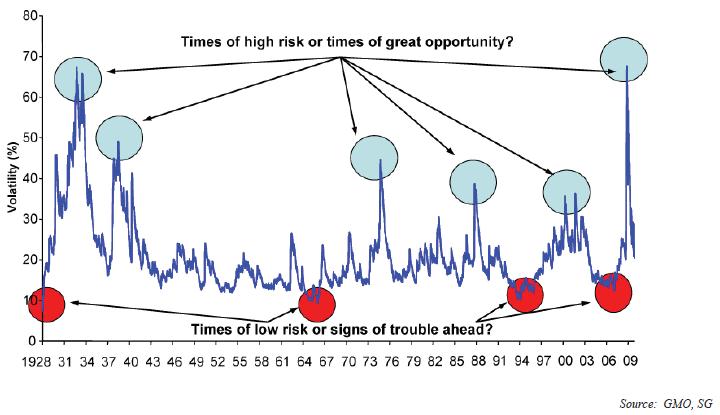

I would add to this sentiment, particularly for equities as an asset class; there is actually more risk (chance of loss) when volatility is low, and less likelihood of loss when volatility is high.

Additionally, not all volatility or standard deviation is created equal. Most investors, for example, do not think that the prospect of achieving returns that are 2 standard deviations ABOVE average is risky, where the opposite is clearly so. So MPT’s cornerstone– its definition of risk– is incomplete at best and at worst, completely misleading.

Vincent continues

Regardless of MPT’s shortcomings on both a theoretical and empirical level, its dominating influence will not easily be dislodged. MPT is deeply woven into the fabric of our financial system, its mathematical grounding and precise answers inspire confidence. Further, its application is crucial in bringing increased scale and profitability to the financial services industry. Few want to see change. As such, common sense and judgment will continue to diminish in importance as top-down, quantitative strategies and blind diversification gain investment dollars.

And this is the part the ticks me off the most. The ideas behind MPT are so self-serving for our industry that despite their shortcomings, we can’t seem to move past them. Of course fear of embracing Maverick Risk (see my recent post) help keep the status quo alive and well

There’s a feeling of safety that accompanies index investing; neither the advisor nor the investor risks losing face or losing a job over putting money to work in a broad index. We enjoy the mathematical certainty of MPT, it’s reassuring that we can fix a value to assets, and that we can quantify risk in a non-subjective manner – free from human error…When defending an entrenched system that furthers the economic interests of powerful entities, the rationale doesn’t need to be sound, it just has to be somewhat convincing.

Vincent’s Prescription

The author contends that smart investors should welcome the dumb money move to highly diversified, passive strategies, while acknowledging if you ARE the dumb money or are forced on some level into limited choices (like 401(k) plan participants or beneficiaries of trusts with bank trustees– at least don’t pay active management fees for closet indexers.

An informed investor should welcome this shift. As highly-diversified strategies gain assets, inefficiencies become more prevalent because share prices are increasingly driven by factors other than fundamentals… there is compelling empirical research that shows active managers who are truly “active,” do persistently outperform indexes. The astute individual investor can seize the opportunity that blind, passive index investing provides in the form of increased market inefficiencies by hiring active managers who have shown the ability to exploit and profit from these inefficiencies.

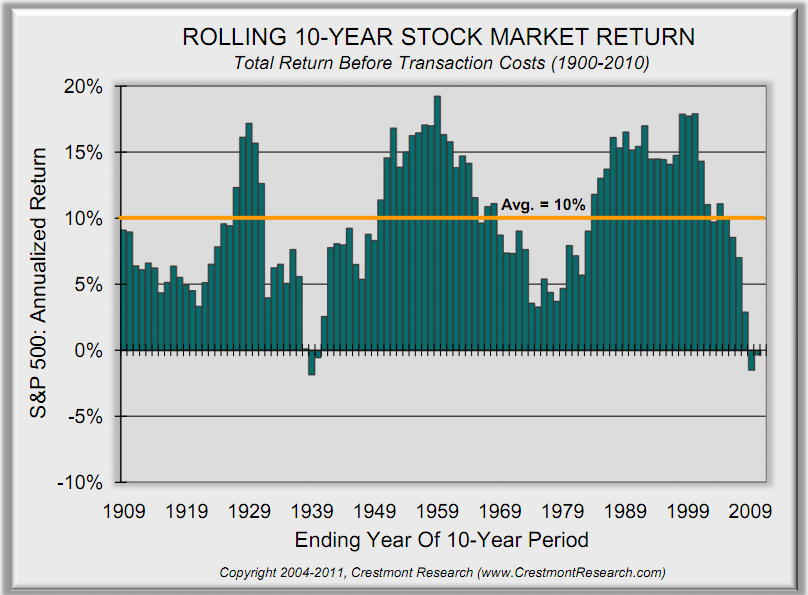

Take advantage of the fact that your neighbors are leaving for passive funds, as their passive investments could provide the inefficiency your manager seeks to exploit. But, by all means, avoid investing in highly diversified active funds whose returns closely match an index. If index returns are what you seek, then pull your money and invest in efficient passive index funds or ETFs (emphasis mine).This is where many investors stop thinking about their portfolio. They say, Yes! index returns is what I seek. After all, if you buy and hold the market you can earn the long-term returns right? Unfortunately, the answer to that is no. The long-term “average” returns are rarely available. In fact, depending on where you are standing, the returns are either much higher, or much lower. Consider this chart fromCrestmont Research which shows that even for periods as long as 10 years, average rarely occurs:

MPT & Asset Allocation

Scott Vincent seems to be focused on encouraging investors to choose the correct managers (truly active, relatively concentrated, fundamentally-focused) WITHIN asset classes like stocks or bonds. And he is certainly compelling. However, as I alluded to earlier, his argument holds sway over the much larger and dangerous consequences of asset allocation.

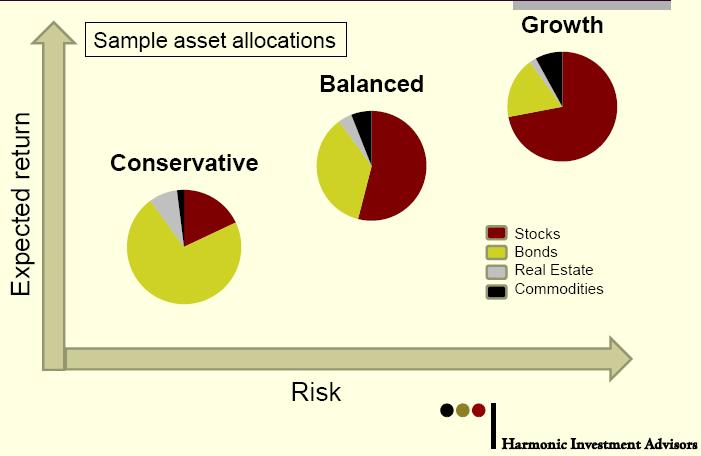

Consider this chart which you’ve probably seen in one form or another. It shows expected risk and return of various mixes of asset classes and the typical approach to asset allocation which Modern Portfolio Theory has spawned:

So what’s wrong with this picture? Lots of things.

The first is the inputs– namely expected returns and volatilities of various asset classes– most investment programs are built on logic like this:

- Bonds will return 5% on average over the long-term but be between 0-10% in any given year

- Stocks will return 10% on average over the long-term but be between -10% and +20% in any given year

- Some might include other nuance regarding different types of bonds like High Yield or different types of stocks like Emerging Markets

- Some might include different types of assets like real estate, commodities, or “alternatives”

The problem of course is this is an incomplete description of investment returns:

- The math contends that returns are randomly and unpredictably distributed around the average

- This “normal distribution” of returns contends that larger market movements outside of the ranges above will be relatively rare

- “Average” returns ignore the role of valuation and the importance of when you start investing (buy) and when you finish (sell) even over multi-decade time horizons

The traditional approach to asset allocation is built on false axioms. The phenomenal secular bull market in stocks and bonds from 1982-1999 created the perfect conditions for the nearly religious acceptance of MPT. In a recent post, Expensive Markets Mean Low (or Negative) Prospective Returns, I made the case that valuation matters greatly and currently portend disappointing returns for both stocks and bonds. Traditional asset allocation has no way of dealing with this in a way that successfully protects portfolios from experiencing meaningful and unnecessary drawdowns.

As colleague Brian McAuley penned in Sitka Pacific’s March 2010 client letter

Whether or not these themes are presented directly, they underpin the advice that most investment advisors give their clients. At its core, the message is usually something similar to this: “The markets are random and unpredictable, so the best way to invest is to properly diversify and wait for the averages to play out.”

However, what most investors seem to be unaware of is that this whole theory of random movement of market prices was proven false over 50 years ago by one of the most influential mathematicians of the 20th century, Benoit Mandelbrot. The random motion of market prices was a very nice theory, but it just doesn’t match what actually happens in the real world.

In a completely random world, a large movement in prices would be a relatively rare event. But we know from market history that large movements in prices happen far more frequently than they should if prices moved completely randomly. In fact, if we look at annual market returns, there are 50% more extreme events than there should be… It’s clear that there are other forces influencing the markets that aren’t taken into account by the statistics of purely random movements—and they have to do with human behavior.

Since the movement of market prices is not random, most investment advice given today that is based on Modern Portfolio Theory is simply wrong. Particularly, the assumption that market risk can be reduced by diversification has led to frequent catastrophic results throughout market history—most recently in 2008.

Although the theory of random market movements was proven false more than 50 years ago for those fluent in mathematics, with multiple bubbles and busts in the last decade it has become painfully obvious to everyone that there is more to market movements besides a Brownian-like random motion. Markets are subject to the rational and irrational decisions made by millions of people, and as such they are prone to cycles of extremes in sentiment and valuation—booms and busts.

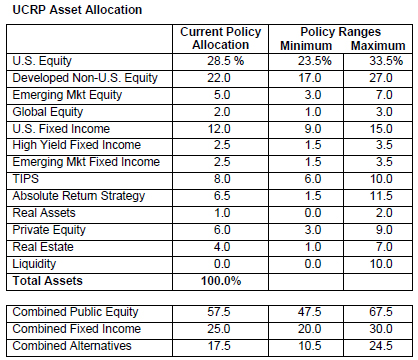

Even those who bill themselves as “active” asset allocators typically only move within a small range of acceptable allocations such as 40-60%. Consider even this progressive asset allocation policy:

My Prescriptions

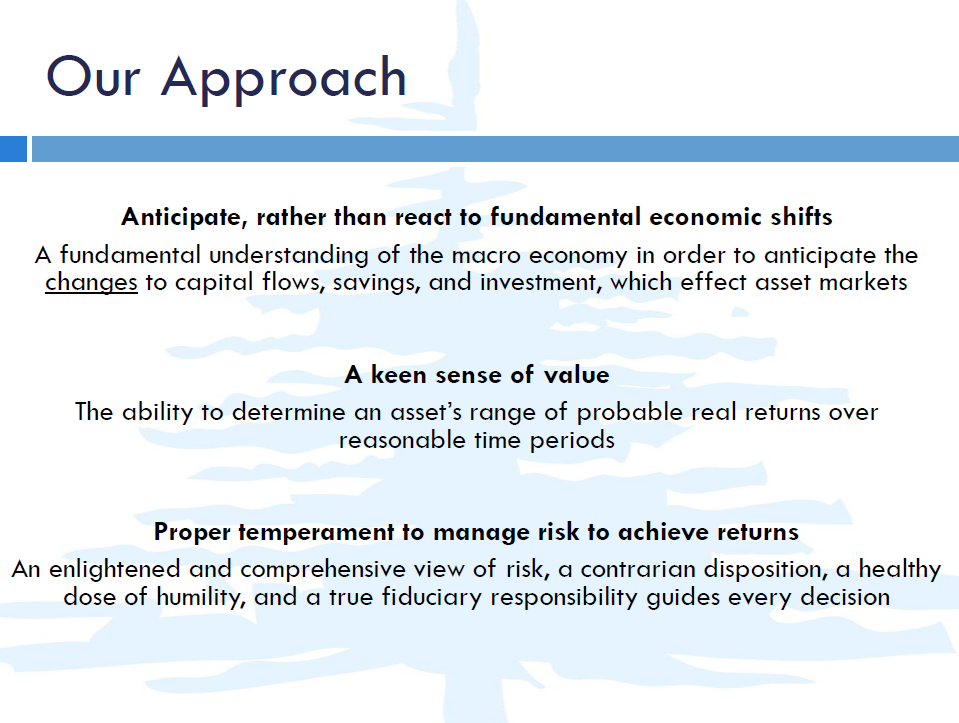

Obviously, I think investors can do better. Just as Scott Vincent highlights the cadre of truly active, relatively concentrated investment managers who have “beaten the market” consistently– there are asset allocation strategies which aim to improve upon the traditional approach. At Sitka Pacific, we’ve taken an “Absolute Return” approach to the markets. From our 2006 Annual Review

We have the flexibility to take more meaningful actions to preserve capital, manage risk and volatility, and invest where the best opportunities are. Our goals are simple: to preserve capital first and generate an absolute positive returns second. In order to achieve those goals we look at the market as a means to generate a return, not something that should be blindly followed. We use the market when it can be useful to us, and can look elsewhere (even to cash) when there is more risk than potential reward in the market. The flexibility to manage risk may prove critical over the next several years.

Lots of managers aim to do the same thing. I’d recommend finding one who not only has demonstrated a successful approach in various market environments, but also whose process seems repeatable and makes sense to you. Take Mebane Faber at Cambria and his GTAA ETF. It’s a pretty straightforward process that using long-term momentum indicators to decide when and when not to be invested in various markets. It’s an improvement on a static approach, but might leave a little something to be desired for folks who wish to have a fundamental approach to their portfolio. John Hussman’s approachat the Hussman Funds is worth a look as well. For Do-it-Yourselfers, I’d recommend this post by David Merkel: The Impossible Dream Project for a good look at how to build your own process. For our approach to be successful, we need 3 Key Traits:

When one is trying to be dynamic and active in their approach, flexibility is hugely important. Whether it’s the inherent inflexibility of an investment committee, the curse of success (overconfidence), ingrained cultural constraints, or simply the challenge of moving around and effectively deploying a large chunk of assets, large, well established firms often lack flexibility.

Folks in this position, MPT devotees, and folks who don’t want to rock the boat too much would be wise to consider several emerging theoretical frameworks which aim to improve upon the status quo.

- Post-Modern Portfolio Theory (PMPT) is compellingly described in this FPA Journal article by Pete Swisher and Gregory Kasten.

- Allocating based on Downside Risk (versus Mean Variance) seems like a no-brainer and should be evaluated by anybody trying to “optimize” portfolio allocations. Here is a good primer.

- Fundamental Indexing: Research Affiliates is a good source.

- Risk Parity, which Bridgewater, PanAgora, and AQR are all pursuing in various forms, takes a different view of targeting acceptable levels of risk as opposed to returns

These approaches all have their own limitations and should be evaluated critically (like anything involving your or your client’s money). Ironically, one can make the argument that “Absolute Return” or GTAA or Fundamental Indexing can be considered as distinct asset classes, with their own projected risk and return characteristics and lower correlations to traditional benchmarks. In this case, MPT would suggest that “efficient” portfolios should have an allocation to them, just as many traditional investors have embraced alternatives to varying degrees.

Regardless of how you are currently invested, the shortcomings of MPT and its pervasiveness in portfolios is becoming increasingly clear. The last two years have given MPT-based investors a reprieve from the secular bear market underway since 2000. The next two years may not be so friendly. Investors should take the leap into truly active investing and asset allocation, even if it just means “trying it” with one or more managers or funds.

Etichette:

articles,

Finance article,

market articles,

trading

BERNANKE: I DIDN’T DO IT!

by Cullen Roche

Ben Bernanke spoke today at the International Monetary Conference in Atlanta. His speech was certainly market moving and as reports of the speech hit the wires the equity markets began to reverse on fears that QE3 is off the table. But there was a more interesting tone in his speech today than we’ve seen in the past. The Chairman was exceptionally defensive. In fact, the entire speech is basically an explanation as to why QE2 did not hurt the economy (of course it did). The most important section is attached:

“While supply and demand fundamentals surely account for most of the recent movements in commodity prices, some observers have attributed a significant portion of the run-up in prices to Federal Reserve policies, over and above the effects of those policies on U.S. economic growth. For example, some have argued that accommodative U.S. monetary policy has driven down the foreign exchange value of the dollar, thereby boosting the dollar price of commodities. Indeed, since February 2009, the trade-weighted dollar has fallen by about 15 percent. However, since February 2009, oil prices have risen 160 percent and nonfuel commodity prices are up by about 80 percent, implying that the dollar’s decline can explain, at most, only a small part of the rise in oil and other commodity prices; indeed, commodity prices have risen dramatically when measured in terms of any of the world’s major currencies, not just the dollar. But even this calculation overstates the role of monetary policy, as many factors other than monetary policy affect the value of the dollar. For example, the decline in the dollar since February 2009 that I just noted followed a comparable increase in the dollar, which largely reflected flight-to-safety flows triggered by the financial crisis in the latter half of 2008; the dollar’s decline since then in substantial part reflects the reversal of those flows as the crisis eased. Slow growth in the United States and a persistent trade deficit are additional, more fundamental sources of recent declines in the dollar’s value; in particular, as the United States is a major oil importer, any geopolitical or other shock that increases the global price of oil will worsen our trade balance and economic outlook, which tends to depress the dollar. In this case, the direction of causality runs from commodity prices to the dollar rather than the other way around. The best way for the Federal Reserve to support the fundamental value of the dollar in the medium term is to pursue our dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability, and we will certainly do that.

Another argument that has been made is that low interest rates have pushed up commodity prices by reducing the cost of holding inventories, thus boosting commodity demand, or by encouraging speculators to push commodity futures prices above their fundamental levels. In either case, if such forces were driving commodity prices materially and persistently higher, we should see corresponding increases in commodity inventories, as higher prices curtailed consumption and boosted production relative to their fundamental levels. In fact, inventories of most commodities have not shown sizable increases over the past year as prices rose; indeed, increases in prices have often been associated with lower rather than higher levels of inventories, likely reflecting strong demand or weak supply that tends to put pressure on available stocks.

Finally, some have suggested that very low interest rates in the United States and other advanced economies have created risks of economic overheating in emerging market economies and have thus indirectly put upward pressures on commodity prices. In fact, most of the recent rapid economic growth in emerging market economies appears to reflect a bounceback from the previous recession and continuing increases in productive capacity, as their technologies and capital stocks catch up with those in advanced economies, rather than being primarily the result of monetary conditions in those countries. More fundamentally, however, whatever the source of the recent growth in the emerging markets, the authorities in those economies clearly have a range of fiscal, monetary, exchange rate, and other tools that can be used to address any overheating that may occur. As in all countries, the primary objective of monetary policy in the United States should be to promote economic growth and price stability at home, which in turn supports a stable global economic and financial environment.”

He gets this partially correct, however, he is still in complete denial over the psychological effects of his policies and the speculative nature of market participants who believed the Fed was printing money and monetizing the debt. In fact, I don’t even think he’s in denial. I think he is being flat out disingenuous and completely unwilling to admit that he is now powerless. The reason I say this is because he discussed the psychological impacts of monetary policy in-depth in a speech in Japan in 2003. He said:

“A period of reflation would also likely provide a boost to profits and help to break the deflationary psychology among the public, which would be positive factors for asset prices as well. Reflation–that is, a period of inflation above the long-run preferred rate in order to restore the earlier price level–proved highly beneficial following the deflations of the 1930s in both Japan and the United States.”

This is exactly right. Beating deflation is largely a psychological battle, however, giving the public the impression that you are going to cause massive inflation through policies that neither you nor the public fully understands is no way to accomplish that effect. An economy battling deflation needs real economic growth and leaders who are not only willing to recognize the problems, but are willing to implement the right policy to combat this horrid economic disease.

The Fed Chairman is clearly being disingenuous with regards to his ability to influence the US economic recovery at this juncture. There’s no way you can be so cognizant of the psychological effects of monetary policy in 2003 and suddenly forget that impact in 2011. Then again, perhaps I am being a bit too hard on the Chairman. He is, after all, the ultimate academic. The banker of all bankers has zero actual banking and market experience so it would not be surprising to find out that the Chairman is oblivious with regards to the psychological impact of monetary policy on markets. Still, I find that hard to believe even though he has shown almost no ability to predict anything and has consistently been reactive to the economy and the markets when he should have been proactive. In other words, the Chairman has displayed a very poor understanding of the way markets react to the real economy and policy.

It’s time for the Wizard to step out from behind the curtain and inform Congress that he is not the omnipotent leader that everyone thinks he is. The Fed desperately needs the help of the US Congress in recognizing the plight that the US economy faces. The longer we wait and the longer Dr. Bernanke pretends to be the Wizard the longer this economic catastrophe will continue.

Etichette:

articles,

Economy article,

Finance article,

market articles

PAUL KRUGMAN & RICHARD KOO ARE BOTH WRONG

by Cullen Roche

There’s been a bit of a spat in the last 24 hours between Paul Krugman and Richard Koo. The two have disagreed on QE since its inception with Koo saying it would do nothing and Krugman maintaining faith in the policy. This is nothing new though. This spat has been going on for decades now. Richard Koo was an early critic of QE in Japan when a young(er) American economist named Paul Krugman went over to Japan to lecture the Japanese on their policy options as deflation dug its heels in. Dr. Krugman was a very vocal advocate of the policy saying that it could alter expectations and generate positive economic growth. Koo maintained that, in a balance sheet recession, the policy would fail to generate any sort of substantive effect on the real economy. Of course, Koo ended up being right about QE in Japan and he’s now being proven right again about QE in the USA.

Now, I have to admit that I am a bit biased in this fight because I’ve been siding with Koo since QE began, but the facts are the facts. QE does not appear to have done a single positive thing for the economy. A few of us (myself and Richard Koo) were particularly vocal critics of the policy from its onset and not for the reasons that most others were (inflation, money printing, debt monetization, etc). It’s now clear that QE didn’t result in hyperinflation, excessive money supply growth, debt monetization and merely generated a margin squeeze on the entire economy, resulted in no real growth and actually resulted in lower real GDP. Thus, it would appear that Koo was right and Krugman was wrong.

But Paul Krugman isn’t having it. Unfortunately, he’s making the same argument he made 9 months ago. He says he wasn’t wrong. He merely claims that he was an advocate of the Fed trying all options and that he was also calling for greater fiscal policy. Let’s review what he actually said:

“I believe that given the grim economic situation, all players in the game should be trying to do whatever they can. There are other things the Fed can do; they would help; uncertainty about how much they would help shouldn’t be a reason not to try.

But it would be a big mistake to count on monetary policy alone. The zero lower bound on short rates really does matter, even if longer-term rates are positive. The Fed cancontrol short-term interest rates, it can influence long rates — there’s a world of difference between those two statements. So it’s not safe to assume that the Fed can, for example, hit any target for nominal GDP that it chooses.

What that means is that while the Fed should be doing more, so should other actors: unconventional monetary policy should go along with fiscal stimulus. The Fed deserves to be chastised for not doing more; that’s not the same as saying that the Fed should be the only target of criticism.”

These comments are actually very similar to what Ben Bernanke said in 2003 regarding QE and how the various arms of the government should work in tandem to achieve their objectives. Mr. Bernanke was an advocate of QE because he also said fiscal policy was necessary in Japan. Unfortunately, his understanding of the Japanese monetary system led him astray and resulted in a misguided belief that QE was necessary to help “finance” any fiscal policy. This is just not how a sovereign currency issuer’s monetary system functions, but that’s for another discussion (see here). I can’t be sure if Paul Krugman is advocating the same approach, but we already know he’s a bit confused about sovereign currency issuers so it wouldn’t be a big leap of faith to conclude as much….The two Princeton professors are very much on the same (wrong) page with regards to QE and have been for a long time.

With regards to trying all policy approaches…look, I’m a big fan of team efforts. Unfortunately, there are times when certain players need to just take a backseat and accept the reality that their participation is unlikely to help. In this case, the Fed was and has been out of bullets. But they continued to heave shots at the hoop with the hope that one of them would land in the basket and they could proclaim to have saved the economy. The Fed shouldn’t just be throwing shots up because they get the ball. That’s not a winning strategy. You have to diagnose the situation and maximize your best weapons in crunch time by ensuring that they’re the ones taking the shots. Richard Koo has been very clear about his position as have I. In a balance sheet recession monetary policy is notoriously ineffective and fiscal policy is the only real tool that can offset the de-leveraging. The history of Japan makes this abundantly clear. We shouldn’t have our least effective players heave shots at the hoop just because they want to try and help the team. But Paul Krugman continues to push the same failing argument he made in Japan in 1998. It was wrong then and it is wrong now.

In that 1998 speech he said:

“this argument against the effectiveness of quantitative easing is simply irrelevant to arguments that focus on the expectational effects of monetary policy. And quantitative easing could play an important role in changing expectations; a central bank that tries to promise future inflation will be more credible if it puts its (freshly printed) money where its mouth is.”

Well, expectations certainly changed. They changed so much that speculators scurried into commodities, causing cost push inflation and causing real GDP to decline as real growth failed to materialize. When Paul Krugman repeated these comments in October of last year I called him out and predicted exactly what would happen:

“Talking a big game about future inflation expectations is great and all, but talk is cheap. Ultimately, we need real positive change in the real economy – more jobs, higher wages, higher net worth. QE doesn’t provide that. You can alter public perception briefly by screaming in the streets, but ultimately, without some real world impact people just begin to ignore you. And this might just be the greatest problem with QE. Not only will it do little to nothing to solve the economic malaise, but it threatens the credibility of the Federal Reserve who has now gone “all in” on a policy tool that I believe Mr. Bernanke himself does not even fully understand. If it doesn’t work the Fed will be viewed as the emperor with no clothes and that will be one more notch on devil’s tool of discouragement. And ultimately, that will have the exact OPPOSITE effect that Mr. Krugman and Mr. Bernanke are hoping for.”

And this gets right to the crux of Dr. Krugman’s confusion regarding QE. He still thinks it’s about size and not quantity. His comments above regarding rates make this clear. He was a vocal advocate last October of “$8-$10B” of QE. But QE is never about size. It is always about price. This is another thing I explained last fall:

“The bigger problem here is not quantity, however. Mr. Krugman appears to believe that the apple (and no, this apple salesman is not selling iPads unfortunately) salesman can rush into the marketplace and scream and wave his hands regarding the new stock of apples he has that is 10X larger than his old stock. “Step right up ladies and gents! Fresh new apples right off the truck! We’ve got 10X more than we had yesterday!”. The problem with this thesis is that, while it might cause a stir in the marketplace (it might even cause a near-term boost in sales – or commodity and equity prices if you will), ultimately, sales will be determined by the willingness of the consumers to purchase. Therein lies the weakness in QE. Because it does not alter net financial assets in the private sector there is no reason to believe that it will alter the real economy in the long-term.”

If you’re a bit confused this explanation of mine from a few weeks ago sheds more light on the issue of price vs quantity and shows why Dr. Krugman is wrong to be discussing quantity:

“When I first discussed QE last August and why it would not contribute positively to economic growth I described how QE was akin to an apple salesman who can’t sell enough apples. So, instead of altering price he merely alters the number of apples on the shelves. Altering reserve balances at banks is perfectly analogous. Giving the banks more reserves does nothing because banks are never reserve constrained. But now all of the experts are trying to convince us that QE just wasn’t tried hard enough! If only the apple salesman had put more apples on the shelves – then his sales would have improved! No, that’s not how monetary policy works. And as I’ve said for many many months now, this obsession with size is entirely misguided. QE2 isn’t about size. It is about price.

QE2 was destined to fail before it ever started. Not because it wasn’t large enough, but because rates can’t be controlled through size. They are controlled by targeting price. The Fed controls the short end of the curve by setting the rate. They do not come out at the FOMC meetings and declare that they will buy $XXXmm in reserves. They announce that the short rate is X.XX%.

With regards to QE2 the Fed has come out and said they are going to buy back a specific number of bonds. And the bond market has yawned at the Fed. In fact, the bond market has spat in their face. Long rates are higher by almost 100 bps since QE2 started and there is no evidence that QE2 is helping to spur the lending markets as the Fed might have hoped. Can you imagine if the Fed set the overnight rate at 0.25% and the market just ignored them and took short rates right up to 1.25%? The Fed would be mocked as a meaningless institution. But in the case of QE2 we make all sorts of excuses about size, real rates, etc in order to shield their impotence.

Had the Fed hoped to control long rates they should have come out and directly stated their target rate. They should have done exactly what they do at the short end – stand guard at that rate and challenge any and all speculators to move the rate.”

QE was destined to fail before it ever began. Not only was it merely an asset swap, but it failed to control rates because it was implemented incorrectly. It altered expectations (as Dr. Krugman hoped), but only for the worse as the commodity surge appears to have negated the entirety of the positive effects from the $100MM tax cut. The fact that prominent economists continue to have so many misconceptions regarding the policy only goes to show that this is an incredibly dangerous policy tool to be swinging around.

But Richard Koo is not without fault in this whole debate. One place where I do agree with Dr. Krugman (and disagree with Richard Koo) is with regards to Koo’s position on the US Dollar. He says there is some risk that QE could cause a collapse in the dollar (he recently reiterated these comments). In his Holy Grail of Macroeconomics Koo states:

“a central bank can always generate hyperinflation by acting so as to lose the public’s trust, its ability to induce modest amounts of inflation depends on whether private businesses are in profit-maximization mode or not.”

Koo resorts to his neoclassical roots here by presuming that bank reserves are lent out and that the central bank can always create inflation if the economy is not in a balance sheet recession. This is factually incorrect. Banks never lend reserves. The fact that we are in a balance sheet recession gives the appearance that reserves are not being lent out, however, the balance sheet recession is only exposing the banking system for what it really is. Banks are never reserve constrained. They lend first and find reserves later. This is a simple reality of modern banking and has been shown in several Fed papers in recent years and is prominently discussed by MMT economists (who are just about the only ones who have these facts accurate).

Koo’s point here is to show that the central bank could potentially generate hyperinflation by being reckless with their policy and losing the trust of the public. I think this is a fundamental misunderstanding of the US monetary system. Helicopter drops (as Koo refers to them in the book) are always fiscal operations (see Scott Fullwiler’s excellent presentation here). The Fed did not monetize the debt. The Fed did not print money. And hyperinflation is a unique event whose historical episodes bear zero resemblance to the modern day United States. Therefore, I think Koo’s fears of a disorderly dollar collapse are totally unfounded. The very foundation from which he is working is fundamentally wrong. And ironically, his misunderstanding stems from the same place that Krugman’s misunderstanding stems from – a basic misunderstanding of the actual operations of a sovereign currency issuer with monopoly supply of currency in a floating exchange rate system.

So, I guess they’re both wrong….At least Koo got the policy right in the first place though…

See the original article >>

Etichette:

articles,

Economy article,

Finance article,

market articles

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)