by Joseph Schuman

So much for the jobs-jobs-jobs agenda.

The epidemic unemployment gripping the the country may still be the top priority of the Federal Reserve. But other issues loom larger for the new majority in the House of Representatives, as Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke learned this morning in his first testimony of the year before a committee that has switched hands to Republicans.

There was little change in Bernanke's outlook from his recent public comments -- an economy picking up steam, inflation that's tame and stubbornly high unemployment that's unlikely to abate anytime soon -- but his audience in the House Budget Committee was ready to shake things up.

Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan started with a warning that the Fed's campaign to thrust $600 billion into the economy through an eight-month bond-buying spree, its biggest effort to boost growth and generate hiring, risks sparking inflation and jeopardizes American fiscal strength.

"My concern is that the costs of the Fed's current monetary policy -- the money creation and massive balance sheet expansion -- will come to outweigh the perceived short-term benefits," Ryan said. "We are already witnessing a sharp rise in a variety of key global commodity and basic material prices, and we know that some producers and manufacturers here in the United States are starting to feel cost pressures as a result."

The epidemic unemployment gripping the the country may still be the top priority of the Federal Reserve. But other issues loom larger for the new majority in the House of Representatives, as Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke learned this morning in his first testimony of the year before a committee that has switched hands to Republicans.

There was little change in Bernanke's outlook from his recent public comments -- an economy picking up steam, inflation that's tame and stubbornly high unemployment that's unlikely to abate anytime soon -- but his audience in the House Budget Committee was ready to shake things up.

Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan started with a warning that the Fed's campaign to thrust $600 billion into the economy through an eight-month bond-buying spree, its biggest effort to boost growth and generate hiring, risks sparking inflation and jeopardizes American fiscal strength.

"My concern is that the costs of the Fed's current monetary policy -- the money creation and massive balance sheet expansion -- will come to outweigh the perceived short-term benefits," Ryan said. "We are already witnessing a sharp rise in a variety of key global commodity and basic material prices, and we know that some producers and manufacturers here in the United States are starting to feel cost pressures as a result."

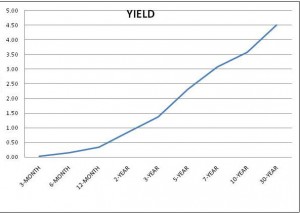

Bernanke stuck to his argument that while prices for gasoline and agricultural commodities have visibly risen, core inflation in the U.S. has remained historically low. And that, he said, gives the Fed room to keep buying bonds in a strategy -- called quantitative easing and nicknamed QE-2 -- that is aimed at lowering long-term interest rates and giving banks more money they can lend.

"The inflation is taking part in emerging markets because that's where the growth is, that's where the demand is and that's where in some cases the economies are overheating," Bernanke said, arguing that it is up to the central banks of those countries to keep their economies balanced.

"The increases in oil prices, for example, are entirely due, according to the International Energy Agency, to increases in demand coming from emerging markets. They're not coming from the United States," Bernanke added. "Of course, that's a serious problem, but monetary policy can't do anything about, say, bad weather in Russia or increases in demand for oil in Brazil and China. What we can do is try to get stable prices and growth here in the United States."

But the concerns aren't just coming from Republicans.

The central bank of China raised interest rates again this week to dampen rising prices in a country that also happens to be the source of many goods that eventually make their way to American consumers. On Tuesday, Brazil reported accelerating inflation in Latin America's biggest economy, which is also a key trading partner of the U.S.

European Central Bank President Jean-Claude Trichet, too, has become increasingly hawkish in warning about inflation threats to the eurozone and beyond.

Even within the Fed, there seems to be growing disagreement. Richard Fisher, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas and a voting member of the Fed's policymaking Federal Open Market Committee, said in a speech Tuesday that the QE-2 purchases make him very wary of inflation and also risk enabling the U.S. government's addiction to debt.

"Barring some unexpected shock to the economy or financial system, I think we are pushing the envelope with the current round of Treasury purchases," Fisher said. "I would be very wary of expanding our balance sheet further. Indeed, given current economic and financial conditions, it is hard for me to envision a scenario where I would not use my voting position this year to formally dissent should the FOMC recommend another tranche of monetary accommodation."

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey Lacker, a nonvoting member of the FOMC this year, voiced similar reservations Tuesday in a separate speech.

Bernanke told Ryan and others on the Budget Committee that the Fed remains "unwaveringly committed" to protecting the country from inflation, and that he and his colleagues frequently re-examine QE-2, which is set to run through June.

He also defended the program from accusations that it adds to U.S. debt, noting that the Fed is buying long-term Treasury securities it will eventually sell and that all the interest from the bonds -- totaling about $125 billion since 2009 -- goes to the Treasury.

But Bernanke, too, warned the Budget Committee that unless Congress and the president can agree to severe adjustments to the budget -- he advocated neither cuts nor new taxes -- "the unsustainable trajectories of deficits and debt" will risk a disaster for the country.

"The question is whether these adjustments will take place through a careful and deliberative process that weighs priorities and gives people adequate time to adjust to changes in government programs or tax policies, or whether the needed fiscal adjustments will come as a rapid and painful response to a looming or actual fiscal crisis," Bernanke said.

"The inflation is taking part in emerging markets because that's where the growth is, that's where the demand is and that's where in some cases the economies are overheating," Bernanke said, arguing that it is up to the central banks of those countries to keep their economies balanced.

"The increases in oil prices, for example, are entirely due, according to the International Energy Agency, to increases in demand coming from emerging markets. They're not coming from the United States," Bernanke added. "Of course, that's a serious problem, but monetary policy can't do anything about, say, bad weather in Russia or increases in demand for oil in Brazil and China. What we can do is try to get stable prices and growth here in the United States."

But the concerns aren't just coming from Republicans.

The central bank of China raised interest rates again this week to dampen rising prices in a country that also happens to be the source of many goods that eventually make their way to American consumers. On Tuesday, Brazil reported accelerating inflation in Latin America's biggest economy, which is also a key trading partner of the U.S.

European Central Bank President Jean-Claude Trichet, too, has become increasingly hawkish in warning about inflation threats to the eurozone and beyond.

Even within the Fed, there seems to be growing disagreement. Richard Fisher, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas and a voting member of the Fed's policymaking Federal Open Market Committee, said in a speech Tuesday that the QE-2 purchases make him very wary of inflation and also risk enabling the U.S. government's addiction to debt.

"Barring some unexpected shock to the economy or financial system, I think we are pushing the envelope with the current round of Treasury purchases," Fisher said. "I would be very wary of expanding our balance sheet further. Indeed, given current economic and financial conditions, it is hard for me to envision a scenario where I would not use my voting position this year to formally dissent should the FOMC recommend another tranche of monetary accommodation."

Richmond Fed President Jeffrey Lacker, a nonvoting member of the FOMC this year, voiced similar reservations Tuesday in a separate speech.

Bernanke told Ryan and others on the Budget Committee that the Fed remains "unwaveringly committed" to protecting the country from inflation, and that he and his colleagues frequently re-examine QE-2, which is set to run through June.

He also defended the program from accusations that it adds to U.S. debt, noting that the Fed is buying long-term Treasury securities it will eventually sell and that all the interest from the bonds -- totaling about $125 billion since 2009 -- goes to the Treasury.

But Bernanke, too, warned the Budget Committee that unless Congress and the president can agree to severe adjustments to the budget -- he advocated neither cuts nor new taxes -- "the unsustainable trajectories of deficits and debt" will risk a disaster for the country.

"The question is whether these adjustments will take place through a careful and deliberative process that weighs priorities and gives people adequate time to adjust to changes in government programs or tax policies, or whether the needed fiscal adjustments will come as a rapid and painful response to a looming or actual fiscal crisis," Bernanke said.

He also reiterated that a failure by Congress to raise the national debt ceiling soon would be "catastrophic."

Congressional Republicans have threatened to block such a move unless President Barack Obama first commits to massive spending cuts. But the Treasury has warned that unless the borrowing limit is raised above the current $14.29 trillion by next month, the U.S. government won't be able to pay interest on Treasury bonds.

Bernanke noted that a default would undermine trust in the U.S. among investors around the world and lead to much higher costs for all future American borrowing.

"We do not want to default on our debts," he said. "It would be very destructive."

Congressional Republicans have threatened to block such a move unless President Barack Obama first commits to massive spending cuts. But the Treasury has warned that unless the borrowing limit is raised above the current $14.29 trillion by next month, the U.S. government won't be able to pay interest on Treasury bonds.

Bernanke noted that a default would undermine trust in the U.S. among investors around the world and lead to much higher costs for all future American borrowing.

"We do not want to default on our debts," he said. "It would be very destructive."