by Kimble Charting Solutions

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

The Consequences of Angela Merkel

Germany has been leading the opposition in the European Union to any write-down

of troubled eurozone members’ sovereign debt. Instead, it has agreed to

establish bailout mechanisms such as the European Financial Stability Facility

and the European Financial Stabilization Mechanism, which can lend up to €500

billion ($680 billion) combined, with the International Monetary Fund providing

an additional €250 billion.

These are essentially refinancing mechanisms. Heavily indebted eurozone members can apply to borrow from them at less than the commercial rate, conditional on their committing to ever more drastic fiscal austerity. Principal and interest on outstanding debt have been left intact. Thus, creditors – mainly German and French banks – are not expected to suffer losses on their existing loans, while borrowers gain more time to “put their houses in order.” That, at least, is the theory.

So far, three countries – Greece, Ireland, and Portugal – have availed themselves of this facility. In mid-July 2011, Greece’s sovereign debt stood at €350 billion (160% of GDP). The Greek government currently must pay 25% for its ten-year bonds, which are trading at a 50% discount in the secondary market.

In other words, investors are expecting to receive only about half of what they are owed. The hope is that the reduction in borrowing costs on new loans, plus the austerity programs promised by governments, will enable bond prices to recover to par without the need for the creditor banks to take a hit.

This is pie in the sky. Unless a large part of its debt is forgiven, Greece will not regain creditworthiness. (Indeed, by most accounts, it is about to default.) And the same is true, albeit to a lesser degree, for other heavily indebted sovereigns.

Any credible bailout plan must require creditor banks to accept that they will lose at least half of their money. In the United States’ successful Brady Bond plan in 1989, the debtors – Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil – agreed to pay what they could. The banks that had loaned them the money replaced the old debt with new bonds at par value, which averaged 50% of the old bonds, and the US government provided some sweeteners.

It was write-offs and devaluations, not austerity programs, that allowed bond prices to recover. In the Greek case, creditors have yet to accept the need for write-offs, and European governments have provided them with no incentives to do so.

Germany’s opposition to debt forgiveness is thus bad economics, bad politics (except at home), and bad history. The Germans should remember the reparations fiasco of the 1920’s. In the Treaty of Versailles, the victorious Allies insisted that Germany should pay for “the cost of the war.” They added up the figures, and in 1921 they presented the bill: Germany “owed” the victors £6.6 billion (85% of its GDP), payable in 30 annual installments. This amounted to transferring annually 8-10% of Germany’s national income, or 65-76% of its exports.

Within a year, Germany had asked for, and obtained, a moratorium. New bond issues, following a big debt write-down in 1924 (the Dawes Plan), enabled Germany to borrow the money to resume payments. There then followed a crazy system: Germany borrowed money from the US in order to repay Britain, France, and Belgium, while France and Belgium used a bit of it to pay back Britain, and Britain used more of it to pay back the US.

This whole tangle of debts was finally de facto written off in 1932 in the middle of the global slump. But, until 1980, Germany continued repaying the loans that it had incurred to pay the reparations.

From the start, the economist John Maynard Keynes had been a fierce critic of the reparations policy imposed on Germany. He made three main points: Germany didn’t have the capacity to pay were it to regain anything like a normal standard of living; any attempt to force it to reduce its standard of living would produce revolution; and to the extent that Germany was able to increase its exports to pay reparations, this would be at the expense of the recipients’ exports. What was needed was cancelation of reparations and inter-Allied war debts as a whole, together with a big reconstruction loan to put the shattered European economies back on their feet.

In 1919, Keynes produced a grand plan for comprehensive debt cancellation, plus a new bond issue, guaranteed by the Allied powers, whose proceeds would go to victors and vanquished alike. The Americans, who would have had to provide most of the money, vetoed the plan.

The point to which Keynes kept returning was that the attempt to extract debt payments over many years would have disastrous social consequences. “The policy of reducing Germany to servitude for a generation, of degrading the lives of millions of human beings, and of depriving a whole nation of happiness should be abhorrent and detestable,” he wrote, “even if it does not sow the decay of the whole civilized life of Europe.”

History never repeats itself exactly, but there are lessons to be learned from that episode. Germans today would say that, unlike reparations, the Greek and Mediterranean debts were voluntarily incurred, not coerced. This raises the question of justice, but not the economic consequences of insisting on payment. Moreover, there is a fallacy of composition: if there are too many debt collectors, they will impoverish the very people on whom their own prosperity depends.

In the 1920’s, Germany ended up having to pay only a small fraction of its reparation bill, but the long time it took to get to that point prevented the full recovery of Europe, made Germany itself the most conspicuous victim of the Great Depression, and bred widespread resentment, with dire political consequences. German Chancellor Angela Merkel would do well to ponder that history.

These are essentially refinancing mechanisms. Heavily indebted eurozone members can apply to borrow from them at less than the commercial rate, conditional on their committing to ever more drastic fiscal austerity. Principal and interest on outstanding debt have been left intact. Thus, creditors – mainly German and French banks – are not expected to suffer losses on their existing loans, while borrowers gain more time to “put their houses in order.” That, at least, is the theory.

So far, three countries – Greece, Ireland, and Portugal – have availed themselves of this facility. In mid-July 2011, Greece’s sovereign debt stood at €350 billion (160% of GDP). The Greek government currently must pay 25% for its ten-year bonds, which are trading at a 50% discount in the secondary market.

In other words, investors are expecting to receive only about half of what they are owed. The hope is that the reduction in borrowing costs on new loans, plus the austerity programs promised by governments, will enable bond prices to recover to par without the need for the creditor banks to take a hit.

This is pie in the sky. Unless a large part of its debt is forgiven, Greece will not regain creditworthiness. (Indeed, by most accounts, it is about to default.) And the same is true, albeit to a lesser degree, for other heavily indebted sovereigns.

Any credible bailout plan must require creditor banks to accept that they will lose at least half of their money. In the United States’ successful Brady Bond plan in 1989, the debtors – Mexico, Argentina, and Brazil – agreed to pay what they could. The banks that had loaned them the money replaced the old debt with new bonds at par value, which averaged 50% of the old bonds, and the US government provided some sweeteners.

It was write-offs and devaluations, not austerity programs, that allowed bond prices to recover. In the Greek case, creditors have yet to accept the need for write-offs, and European governments have provided them with no incentives to do so.

Germany’s opposition to debt forgiveness is thus bad economics, bad politics (except at home), and bad history. The Germans should remember the reparations fiasco of the 1920’s. In the Treaty of Versailles, the victorious Allies insisted that Germany should pay for “the cost of the war.” They added up the figures, and in 1921 they presented the bill: Germany “owed” the victors £6.6 billion (85% of its GDP), payable in 30 annual installments. This amounted to transferring annually 8-10% of Germany’s national income, or 65-76% of its exports.

Within a year, Germany had asked for, and obtained, a moratorium. New bond issues, following a big debt write-down in 1924 (the Dawes Plan), enabled Germany to borrow the money to resume payments. There then followed a crazy system: Germany borrowed money from the US in order to repay Britain, France, and Belgium, while France and Belgium used a bit of it to pay back Britain, and Britain used more of it to pay back the US.

This whole tangle of debts was finally de facto written off in 1932 in the middle of the global slump. But, until 1980, Germany continued repaying the loans that it had incurred to pay the reparations.

From the start, the economist John Maynard Keynes had been a fierce critic of the reparations policy imposed on Germany. He made three main points: Germany didn’t have the capacity to pay were it to regain anything like a normal standard of living; any attempt to force it to reduce its standard of living would produce revolution; and to the extent that Germany was able to increase its exports to pay reparations, this would be at the expense of the recipients’ exports. What was needed was cancelation of reparations and inter-Allied war debts as a whole, together with a big reconstruction loan to put the shattered European economies back on their feet.

In 1919, Keynes produced a grand plan for comprehensive debt cancellation, plus a new bond issue, guaranteed by the Allied powers, whose proceeds would go to victors and vanquished alike. The Americans, who would have had to provide most of the money, vetoed the plan.

The point to which Keynes kept returning was that the attempt to extract debt payments over many years would have disastrous social consequences. “The policy of reducing Germany to servitude for a generation, of degrading the lives of millions of human beings, and of depriving a whole nation of happiness should be abhorrent and detestable,” he wrote, “even if it does not sow the decay of the whole civilized life of Europe.”

History never repeats itself exactly, but there are lessons to be learned from that episode. Germans today would say that, unlike reparations, the Greek and Mediterranean debts were voluntarily incurred, not coerced. This raises the question of justice, but not the economic consequences of insisting on payment. Moreover, there is a fallacy of composition: if there are too many debt collectors, they will impoverish the very people on whom their own prosperity depends.

In the 1920’s, Germany ended up having to pay only a small fraction of its reparation bill, but the long time it took to get to that point prevented the full recovery of Europe, made Germany itself the most conspicuous victim of the Great Depression, and bred widespread resentment, with dire political consequences. German Chancellor Angela Merkel would do well to ponder that history.

Robert Skidelsky, a member of the British House of

Lords, is Professor Emeritus of Political Economy at Warwick University.

Decision Time for the Eurozone

Germany’s arguments against introducing Eurobonds, expanding the eurozone’s

bailout fund, and instituting a comprehensive system of economic governance are

transparent and easy to understand. But are they right?

The Germans fear that such innovations would lead to a rise in domestic borrowing costs, and to direct and indirect fiscal transfers to poorer countries. Moreover, they warn of the moral hazard generated by relieving over-indebted countries from the pressure to put their public finances in order. Third, they cite treaty-related and constitutional difficulties in establishing rules and procedures that would simulate a “fiscal union.” Finally, the need to move ahead with European unification in order to legitimize the inevitable infringement of over-indebted countries’ sovereignty might eventually infringe upon German sovereignty as well.

On the other hand, refusing to accept the growing consensus that fiscal union is the key to resolving the debt crisis exposes the eurozone, and Germany, to serious risks. Sticking to half-measures exacerbates markets’ impatience and provokes increasingly determined speculative attacks, not only on the weaker peripheral countries, but also on core AAA-rated countries – like France and, eventually, Germany itself – whose banking sectors hold large volumes of peripheral countries’ debt.

Indeed, weakening banking conditions are emerging as a major threat to the eurozone’s recovery and stability. In the event of sovereign defaults, moreover, the cost of bailing out the banks may far exceed the cost of issuing Eurobonds or instituting a reasonable transfer regime. Investors need to be reassured that debt-service costs are under control, and that debt volumes and deficit limits are firmly monitored in order to minimize default risks and strengthen banks’ ability to lay the groundwork for sustainable growth.

In fact, the emerging systemic risk concerning the sustainability of the eurozone produces a vicious circle. Systemic risk raises doubts about the solvency of over-indebted countries, which means that these countries’ efforts to consolidate their fiscal position and promote reform do not lead to improvement in financial conditions, which is essential for overcoming the crisis and promoting recovery. As a result, fiscal consolidation becomes increasingly difficult to achieve, inviting renewed speculative attacks.

Moreover, viewed from a wider perspective, economic and social turbulence on Europe’s southern periphery will constitute a geopolitical risk. That risk would be exacerbated by the eruption of a major default-related crisis within the eurozone, which might not be contained and, through a Lehman-like domino sequence, could jeopardize the entire edifice.

The eurozone’s dilemmas, and the pros and cons of proposed solutions, can be debated endlessly. It could be argued, for example, that Eurobonds would allow eurozone members to pool their financial strength and, by enhancing the attractiveness of the euro as a reserve currency, hold down borrowing costs to such an extent that AAA-rated countries are not overburdened. Legal problems could also be overcome in the short term by designing Eurobonds to include credit guarantees, repayment priorities, and the use of specific tax streams as collateral.

Proposals to limit moral hazard, meanwhile, would do so by limiting Eurobonds to 60% of GDP – the eurozone’s current ceiling for member states’ public debt. A more substantial constraint would be to establish a tougher disciplinary regime on fiscally profligate countries as part of a reinforced institutional framework.

Political problems, however they are addressed, should be weighed against the vulnerability of European banks. Germany’s banks today are the most highly leveraged of any of the major advanced economies, while at the start of the crisis they held close to one-third of all loans made to the public and private sectors of Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Italy. So long as the eurozone’s systemic risk is not addressed, sovereign defaults are not unlikely, leading to extended bank bailouts that could carry unacceptable costs. In that case, a full-blown banking crisis could bring about a depression in the eurozone and, perhaps, globally.

Europe-wide bank recapitalization is essential in the short term to contain the cost arising from possible sovereign defaults. However, addressing the eurozone’s deeper defects cannot be postponed endlessly. Of course, in the midst of so much uncertainty, it is remarkable that the over-indebted countries’ consolidation efforts remain broadly on track; but the European Central Bank’s continued bond-buying and liquidity support is only a temporary palliative.

An impasse is inevitable, so playing for time is not a solution. By contrast, a combination of Eurobonds, a fully-fledged debt facility, enhanced powers for the ECB so that it can act as a lender of last resort, and solid economic governance would work. In the longer term, radical reforms in capital, product, and labor markets will also be needed, complemented by a stronger and more cohesive investment strategy at the European level, aimed at boosting competitiveness and restoring growth prospects.

European competitiveness does not have only a global dimension. Large discrepancies exist within the eurozone, reflected in structural trade imbalances between the core and the periphery that lie at the heart of the debt crisis. The eurozone’s cohesion and future growth depend critically on creating a framework – through grants and loans – for investment capital to flow to the poorer countries in order to close the competitiveness gap.

To borrow a phrase from the financial world, the euro is too big to fail. Decisions should be taken sooner rather than later, so that the eurozone itself shapes events, rather than being commanded by them.

The Germans fear that such innovations would lead to a rise in domestic borrowing costs, and to direct and indirect fiscal transfers to poorer countries. Moreover, they warn of the moral hazard generated by relieving over-indebted countries from the pressure to put their public finances in order. Third, they cite treaty-related and constitutional difficulties in establishing rules and procedures that would simulate a “fiscal union.” Finally, the need to move ahead with European unification in order to legitimize the inevitable infringement of over-indebted countries’ sovereignty might eventually infringe upon German sovereignty as well.

On the other hand, refusing to accept the growing consensus that fiscal union is the key to resolving the debt crisis exposes the eurozone, and Germany, to serious risks. Sticking to half-measures exacerbates markets’ impatience and provokes increasingly determined speculative attacks, not only on the weaker peripheral countries, but also on core AAA-rated countries – like France and, eventually, Germany itself – whose banking sectors hold large volumes of peripheral countries’ debt.

Indeed, weakening banking conditions are emerging as a major threat to the eurozone’s recovery and stability. In the event of sovereign defaults, moreover, the cost of bailing out the banks may far exceed the cost of issuing Eurobonds or instituting a reasonable transfer regime. Investors need to be reassured that debt-service costs are under control, and that debt volumes and deficit limits are firmly monitored in order to minimize default risks and strengthen banks’ ability to lay the groundwork for sustainable growth.

In fact, the emerging systemic risk concerning the sustainability of the eurozone produces a vicious circle. Systemic risk raises doubts about the solvency of over-indebted countries, which means that these countries’ efforts to consolidate their fiscal position and promote reform do not lead to improvement in financial conditions, which is essential for overcoming the crisis and promoting recovery. As a result, fiscal consolidation becomes increasingly difficult to achieve, inviting renewed speculative attacks.

Moreover, viewed from a wider perspective, economic and social turbulence on Europe’s southern periphery will constitute a geopolitical risk. That risk would be exacerbated by the eruption of a major default-related crisis within the eurozone, which might not be contained and, through a Lehman-like domino sequence, could jeopardize the entire edifice.

The eurozone’s dilemmas, and the pros and cons of proposed solutions, can be debated endlessly. It could be argued, for example, that Eurobonds would allow eurozone members to pool their financial strength and, by enhancing the attractiveness of the euro as a reserve currency, hold down borrowing costs to such an extent that AAA-rated countries are not overburdened. Legal problems could also be overcome in the short term by designing Eurobonds to include credit guarantees, repayment priorities, and the use of specific tax streams as collateral.

Proposals to limit moral hazard, meanwhile, would do so by limiting Eurobonds to 60% of GDP – the eurozone’s current ceiling for member states’ public debt. A more substantial constraint would be to establish a tougher disciplinary regime on fiscally profligate countries as part of a reinforced institutional framework.

Political problems, however they are addressed, should be weighed against the vulnerability of European banks. Germany’s banks today are the most highly leveraged of any of the major advanced economies, while at the start of the crisis they held close to one-third of all loans made to the public and private sectors of Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, and Italy. So long as the eurozone’s systemic risk is not addressed, sovereign defaults are not unlikely, leading to extended bank bailouts that could carry unacceptable costs. In that case, a full-blown banking crisis could bring about a depression in the eurozone and, perhaps, globally.

Europe-wide bank recapitalization is essential in the short term to contain the cost arising from possible sovereign defaults. However, addressing the eurozone’s deeper defects cannot be postponed endlessly. Of course, in the midst of so much uncertainty, it is remarkable that the over-indebted countries’ consolidation efforts remain broadly on track; but the European Central Bank’s continued bond-buying and liquidity support is only a temporary palliative.

An impasse is inevitable, so playing for time is not a solution. By contrast, a combination of Eurobonds, a fully-fledged debt facility, enhanced powers for the ECB so that it can act as a lender of last resort, and solid economic governance would work. In the longer term, radical reforms in capital, product, and labor markets will also be needed, complemented by a stronger and more cohesive investment strategy at the European level, aimed at boosting competitiveness and restoring growth prospects.

European competitiveness does not have only a global dimension. Large discrepancies exist within the eurozone, reflected in structural trade imbalances between the core and the periphery that lie at the heart of the debt crisis. The eurozone’s cohesion and future growth depend critically on creating a framework – through grants and loans – for investment capital to flow to the poorer countries in order to close the competitiveness gap.

To borrow a phrase from the financial world, the euro is too big to fail. Decisions should be taken sooner rather than later, so that the eurozone itself shapes events, rather than being commanded by them.

Yannos Papantoniou was Economy and Finance Minister

of Greece from 1994 to 2001 and is currently President of the Center for

Progressive Policy Research, an independent think tank.

Six Things the Fed May Announce Tomorrow (But Likely Won't); Would Any of Them Matter? Gaming the Reaction

by Mike Shedlock

Courtesy Breakfast with Dave (via Zerohedge Forget Operation Twist: Rosenberg Says Bernanke Will Shock

Everyone With What Is About To Come), let's take a look at some ideas of

Dave Rosenberg and see how likely each one is, and whether any of them would

matter.

The consensus view that the Fed is going to stop at 'Operation Twist' may be in for a surprise. It may end up doing much, much more. And this may be one of the reasons why the stock market is starting to rally (a classic 50%+ retracement, which always occur after the first 20% down-leg in a cyclical bear market would imply a test of 1,250 on the S&P 500 at the very least). Hedge funds do not want to be short ahead of next week's FOMC meeting, and who can blame them?The above from Rosenberg at Gluskin Sheff, from "Breakfast with Dave", via ZeroHedge.

In other words, if Bernanke wants to juice the stock market, then he must do something to surprise the market. 'Operation Twist' is already baked in, which means he has to do that and a lot more to generate the positive surprise he clearly desires (this is exactly what he did on August 9th with the mid-2013 on- hold commitment). It seems that Bernanke, if he wants the market to rally, is going to have to come out with a surprise next Wednesday. If he doesn't, then expect a big selloff.

What he is likely to do is another story, but here are some options:

- Expand the balance sheet further and simply buy more bonds (at the longer end of the curve).

- Eliminate the interest paid to commercial banks on excess reserves (to try to spur lending).

- Announce an explicit ceiling on the 10-year note yield (say 1.5%), which the Fed has done in the distant past. Based on Bernanke's prior rhetoric, this would seem to be a preferred strategy (though the Fed relinquishes control of the balance sheet).

- Buy foreign securities (bail out Europe and weaken the U.S. dollar — talk about killing two birds with one policy stone).

- Announce an explicit higher inflation target or perhaps a lower unemployment rate target (i.e. reinforce the DUAL mandate).

- As Mr. Bernanke stated for the record in November 2002, the Fed does have broad powers to lend to the private sector indirectly via banks, through the discount window. It could offer fixed-term loans to banks at low or zero interest, with a wide range of private assets (including, among others, corporate bonds, commercial paper, bank loans, and mortgages) deemed eligible as collateral. For example, the Fed might make 90-day or 180-day zero-interest loans to banks, taking corporate commercial paper of the same maturity as collateral. Such a program could significantly reduce liquidity and term premiums on the assets used as collateral. Reductions in these premiums would lower the cost of capital both to banks and the nonbank private sector.

Note that this is all for a trade. As we saw back on August 9th, we had a huge rally but the market is no higher today than it was then. All we have seen since is a huge amount of volatility.

Mish Analysis of 6 Alternatives

- Buy the long end of the curve: What would it do? 10-Year yields are near all-time below 2%. Would another .5% lower to 1.5% accomplish anything? About the only thing I can think it might do is increase the Fed's exit problem down the road.

- Eliminate Interest on Excess Reserves: I think the Fed should eliminate interest on reserves because printing money then handing interest straight over to banks on that money is outrageous. However, banks are capital impaired. Paying interest on excess reserves is one way of slowly recapitalizing banks over time. It would be a huge policy error for the Fed (from their point of view, not mine), to eliminate interest on excess reserves.

- Announce an explicit ceiling on the 10-year note yield (say 1.5%): Rosenberg calls this the preferred scenario. It has three problems: It will not accomplish much, if anything, for the real economy. It would increase the exit problem of the Fed down the road. And worst of all it would increase the exit problem by an unknown amount. Defending an interest rate target, as Switzerland just did, means buying unlimited quantities of treasuries from any sellers.

- Buy foreign securities: This one is interesting, and little discussed. Moreover, the market is clearly focused on problems in Europe. Were the Fed to announce backstopping debt of Italy, it could easily start a huge market reaction (if a market reaction is the goal). However, there are obvious political problems of this policy and if the ECB will not do buy sovereign debt, why should the Fed? Note that once the EFSF is in place the ECB stops buying debt.

- Announce an explicit higher inflation target or perhaps a lower unemployment rate target: The goal of driving rates lower while announcing a higher interest rate target sure seems counterproductive, especially at the long-end of the yield curve. Should the Fed announce a lower unemployment target, members of Congress would pressure the Fed until that goal was reached. The Fed most assuredly will not want that pressure.

- Fixed-term loans to banks at low or zero interest: Banks will not lend for 10 years or even 2 years (remember they are capital impaired and have few good credit risks willing to borrow) if the Fed will only backstop the loan for 90 or 180 days. I am not sure the Fed would try this anyway, but if they did I fail to see how it would spur much lending. It does nothing to solve capital impairment.

Problems Everywhere

I see huge potential problems for all 6 of Rosenberg's alternative.

The most bang-for-the-buck (if the goal was to goose the markets), would come from bailing out Europe. Moreover, I suspect Treasury Secretary Geithner might even be pushing Bernanke in that direction with his TALF for Europe ideas.

However, bailing out Europe would be one of the more politically risky choices.

Would that stop Bernanke? Probably, at least for now, but perhaps not down the road when things become unglued in Europe.

Operation Twist Likely

My assessment of the situation is that Operation Twist (selling the short end of the curve and buying the long end to keep from expanding the Fed's balance sheet) will not do any good.

Yet, the Fed will not do much more than that, other than a little extra yapping about what they might do later. When it comes to "later" any of the six items above are fruitful grounds for hope, even though such hope is misplaced as noted by the discussion of problems above.

Gaming the Reaction

The market focus is clearly on Europe. Should good news come out tomorrow say 30 minutes after Bernanke makes his announcement, whatever Bernanke says may be meaningless, even in the short-term.

With that in mind, we just might see an announcement tomorrow afternoon by the EU and IMF that Greece was approved for the next tranche of loans

Thus, meaningless statements from Europe may easily (and temporarily) override meaningless statements from the Fed.

Perfect Storm For A Tsunami of Gold Demand

By Frank Holmes

Increases in demand from China and India have driven a 7.5 percent increase in demand for gold jewelry during the first half of the year despite a 25 percent increase in the price, according to a report released this week from GFMS. However, much of India’s potential gold demand remains untapped.

Toussaint highlighted an interesting fact: Of the roughly 800 tons of gold imported to India each year, only the top 40 percent of Indian households purchase all of the country’s gold, says Toussaint. The other 60 percent of Indians, who may have the same adoration for gold and celebrate Ramadan and Diwali, historically may not have had access to purchase gold. This large population represents a huge untapped market. To fulfill demand, the WGC has created a program with Indian post offices to distribute coins and small pieces of gold. Toussaint says right now there are 700 post offices in the rural areas servicing 90,000 customers and he expects that number to grow. This market is worth pursuing based on McKinsey’s research that a “huge wealth creation wave” is developing in India. As Toussaint puts it, “if purchase patterns continue, we will see from 2005 to 2025, a four times larger gold market in India.”

This is a fascinating idea because very few entities other than the post office have the network and infrastructure necessary to reach beneath the surface of the world’s largest gold market.

India may be the world’s largest gold market, but in China, gold buying has become so significant that the country has become the fastest-growing market for gold jewelry in the world. Not only are Chinese purchasing increasing amounts of gold, they prefer pure 24-carat gold. This high-quality gold is given to celebrate special occasions, such as birthdays, and purchased for a bride at her wedding. In 2010, 6.6 million brides will make gold a part of their ritual as the yellow metal signifies the importance of a long-term relationship, says the WGC website.

While jewelry represents a large percentage of gold purchases in the country, Chinese can also purchase gold at their local bank. WGC formed a partnership with the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC Bank), the largest bank by deposits in the world. They began offering a “Gold Accumulation Plan” that lets investors buy and accumulate small portions of gold over time. Similar to a bank account, people participating have access to the underlying gold or the cash value at any point. Since it was launched in December 2010 through this summer, the ICBC has an estimated 1.7 million accounts, with an accumulation of more than 12,000 kilograms of gold.

After India and China led the global demand for gold, accounting for 52 percent of 2010 tonnage, the GFMS says the two Asian countries have “continued impressive growth” this year. Gold buying in India jumped 38 percent during the second quarter alone. GFMS reported China’s gold purchases jumped 90 percent on a year-over-year basis through June. This is a follow up to the 75 percent increase in gold demand the country experienced last year.

This share tops all of North America, which accounts for 8 percent, Europe and Russia, which account for 13 percent, and even the Middle East and Turkey, which together account for 12 percent. North American gold demand fell 12 percent during the first half of 2011 due to the slumping U.S. economy and rising prices.

David Lamb, the WGC’s managing director for jewelry, recently told Reuters there is a “significant tidal shift to the Asian markets, to India and China in particular, and gold rising upwards and disappearing from the mass merchandising in the West.”

Central Banks Load Up on Gold

Demand for gold isn’t only coming from the residents of China and India. There’s been a huge sentiment shift among central banks as well. Toussaint noted how, after many years of selling, central banks have become net buyers of gold. He says, “Western Central banks have essentially shut the tap off, and the vast majority of the buying is coming from Eastern central banks.”

In just the first half of this year, official sector purchases are up three-fold over the 2010 total to 216 tons, accord to the GFMS report. GFMS says the rise is largely due to low sales levels from Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) signatories and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) completing its sales program at the end of 2010. In addition, other countries have gobbled up gold in an effort to diversify reserves away from the U.S. dollar. Scotia Capital estimates central banks’ total purchases of gold will reach 248 tons by year-end.

Some of the big buyers have been Mexico (whose central bank purchased roughly 100 tons of gold earlier this year), Korea (purchased 25 tons in June), Thailand (purchased nearly 19 tons in June) and Russia (which has purchased over 50 tons of gold from its domestic market year-to-date).

Toussaint says Eastern central banks are “catching up with the rest of the world” because their current allocation is tiny right now. However, whenever the WGC discusses these buying habits with the central banks of Korea, Taiwan and other Asian countries, they consistently say that they are interested in gold, and looking to hold it over the long-term. In other words, he says, this is not a “knee-jerk reaction to the direction of the dollar.”

GFMS also believes that this could be just the beginning. In a release announcing the report, Philip Klapwijk, Global Head of Metals Analytics at GFMS, said, “we are in essence in chapter three of the central bank story—we’ve left behind a period of heavy net sales, then a short period of neutrality and we’re now in a new environment of heavy buying.”

Etichette:

articles,

Economy article,

Finance article,

gold,

metals

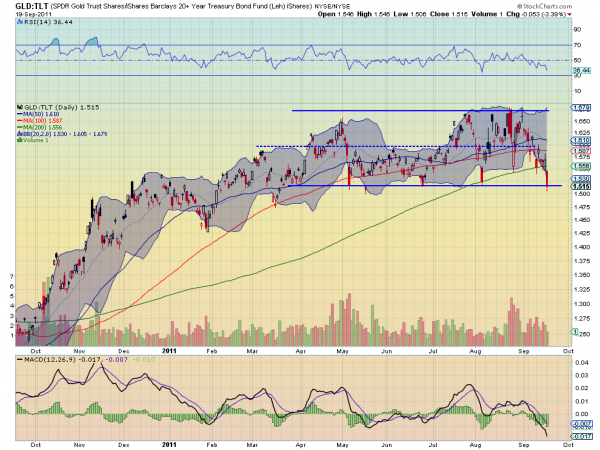

Gold and Treasuries Near a Trigger

by Greg Harmon

Gold has a technical relationship with many other market segments. Looking at

its relationship with US Treasuries it s now at a critical juncture. Below is a

ratio chart of the SPDR Gold Trust ($GLD)

against the iShares Barclays 20+ Year Treasury Bond Fund ($TLT).

Notice how this ratio has been in a range between 1.51 and 1.67 since April. A

pretty tight correlation for this period. But now as it

approaches the bottom rail of this channel there are signs that it may crack.

First the Relative Strength Index (RSI) has been trending lower, not a sharp

move like the last time it bottomed. Next the Moving Average Convergence

Divergence (MACD) indicator has been negative for most of the move down and is

just now becoming more negative again. The volume on this move lower is much

bigger than the last test as well. Finally it closed under the 200 day Simple

Moving Average (SMA) yesterday for the first time since September 30th, just 10

days after the S&P 500 broke out of its bottoming pattern to start the move

higher. It may hold the channel and and reverse back higher, but a breakdown,

indicating a flow from Gold into US Treasuries could cause a powerful change in

the market. Be mindful.

Etichette:

Analysis Technic,

analysis technic article,

articles,

gold,

metals

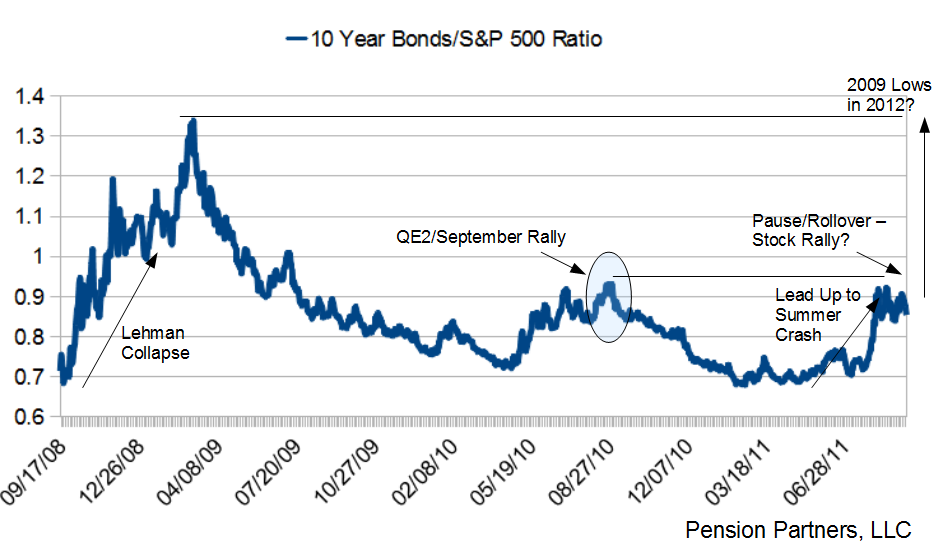

What Does the Ratio Between Bonds/Stock Suggest?

Click for larger chart

>

Michael Gayed of Pension Partners wonders if that the current Stock/Bond

ratio is suggesting a rally:

“The chart above shows the price ratio of the 7-10 Year Treasury ETF relative to the S&P 500. Prior to the Summer Crash of August, Treasuries began to slowly outperform equities before spiking as macro problems came into focus. Interestingly, notice that the relationship of bonds to stocks whereby bonds outperform stocks has been stuck in a holding pattern for the past few weeks. All this despite global news seemingly getting worse (no jobs in U.S., possible Recession, Greece, Italy, etc). This is indicative of a high probability rally in risk assets as investors begin to realize the bonds are no longer out-pacing stocks in the face of very negative macro news.

Investing is all about probabilities and the odds do suggest that for now, we could be in a very real risk-on moment (right when no one reading the news thinks we should be). Of course, should a Lehman-like event occur, all bets are off since the possibility does remain that bonds could spike once again and reach for the 2009 relative peak (March 2009 equities lows)…”

See the original article >>

Etichette:

articles,

Economy article,

Finance article,

financials,

T-Bond

Downleg in Crude Oil

By: Mike_Paulenoff

Nearby NYMEX crude oil finally proved the chart work correct as it plunged from

the upper portion of its September congestion pattern (89.00-90.00) to the lower

portion (86.00-84.00). The decline from last Thursday's lower recovery high at

90.15 into this morning's low at 84.93 has the look and structure of a completed

downleg.

If accurate, this means that a period of upside backing and filling towards

its key near-term breakdown area (86.50-87.50) could be in store in the upcoming

hours. It is for this reason we exited our inverse (short) position in the

ProShares UltraShort DJ-UBS Crude Oil (NYSE: SCO).

Apart from this shorter-term trading strategy and outlook, my longer-term work on NYMEX crude argues strongly that a counter-trend recovery period from the August 8 low at 75.71 ended at the September 13 high at 90.52 and that a new downleg has commenced that should revisit and likely break the August low. ETF traders may want to keep an eye on the U.S. Oil Fund ETF (USO).

Apart from this shorter-term trading strategy and outlook, my longer-term work on NYMEX crude argues strongly that a counter-trend recovery period from the August 8 low at 75.71 ended at the September 13 high at 90.52 and that a new downleg has commenced that should revisit and likely break the August low. ETF traders may want to keep an eye on the U.S. Oil Fund ETF (USO).

Etichette:

Analysis Technic,

analysis technic article,

articles,

crude oil,

energy,

oil

Another Warning Sign

I wrote these words back on June 24, 2011: “This is the first real technical warning sign that the market

is on the verge of breaking down and the economy is on the verge of a

recession.” I was referring to a monthly chart of the i-Shares MSCI

Emerging Market Index (symbol: EEM), which was displaying a pattern consistent

with past market tops.

Now 3 months later, we once again turn to EEM and say,

“be careful”. See figure 1, a weekly chart of EEM. The black and red dots are

key pivot points, which are the best areas of buying (support) and selling

(resistance). EEM is threatening to close (on a weekly basis) below the most

recent key pivot point or support area at 39.68. This would be bearish. In

particular, this could be very bearish. With investor sentiment so extreme, we

should have seen a bounce at these levels. Not only haven’t we seen the bounce

in EEM, but we are actually seeing prices (maybe) break through a support area.

This has a high likelihood of leading to a waterfall decline (if there is a

weekly close below 39.68).

Figure 1.

EEM/ weekly

The market action is becoming increasingly

narrow and as we discussed yesterday, it is concentrated in

the “go to” issues of the NASDAQ100. Copper, EEM, China, and Europe are

technically looking weak. However, any such proclamation that the world is

ending is on hold until after the Fed meeting on Wednesday. Who knows…maybe

they have a plan to bail out the world?

Etichette:

Analysis Technic,

analysis technic article,

articles,

Index

As The Shadow Banking System Imploded In Q2, Bernanke's Choice Has Been Made For Him

by Tyler Durden

With the FOMC meeting currently in full swing, speculation is rampant what

will be announced tomorrow at 2:15 pm, with the market exhibiting its now

traditional schizophrenic mood swings of either pricing in QE 6.66, or,

alternatively, the apocalypse, with furious speed. And while many are convinced

that at least the "Twist" is already guaranteed, as is an IOER cut, per

Goldman's "predictions" and possibly something bigger, as per David Rosenberg

who thinks that an effective announcement would have to truly shock the market

to the upside, the truth is that the Chairman's hands are very much tied.

Because, all rhetoric and political posturing aside, at the very bottom it is

and has always been a money problem. Specifically, one of

"credit money." Which brings us to the topic of this post. When

the Fed released its quarterly Z.1 statement

last week, the headlines predictably, as they always do, focused primarily

on the fluctuations in household net worth (which is nothing but a proxy for the

stock market now that housing is a constant drag to net worth) and to a lesser

extent, household credit. Yet the one item that is always

ignored, is what is by and far the most important data in the Z.1,

and what the Fed apparatchiks spend days poring over, namely the update on the

liabilities held in the all important shadow banking system. And with

the data confirming that the shadow banking system declined by $278 billion in

Q2, the most since Q2 2010, it is pretty clear that Bernanke's choice has

already been made for him. Because with D.C. in total fiscal stimulus

hiatus, in order to offset the continuing collapse in credit at the financial

level, the Fed will have no choice but to proceed with not only curve flattening

(to the detriment of America's TBTF banks whose stock prices certainly reflect

what a complete Twist-induced flattening of the 2s10s implies) but offsetting

the ongoing implosion in the all too critical, yet increasingly smaller, shadow

banking system. And without credit growth, at either the commercial bank, the

shadow bank or the sovereign level, one can kiss GDP growth,

and hence employment, and Obama's second term goodbye.

As the two charts below demonstrate, the economy's ongoing inability to

create any growth in the shadow banking system, primarily as a result of the

complete shut down of the securitization machine, has been and continues to be,

the biggest threat to the Fed. Specifically, after hitting an all time high of

$20.9 trillion in March of 2008, this all too critical source of "credit money"

has collapsed by a whopping 25%: since the peak $5.5 trillion of credit,

and not just any credit, but shadow, and thus non-regulated credit, has

evaporated! And as Q2 demonstrated, after almost bottoming in Q1

following a decline of just $57 billion, or the smallest Q/Q decline since Q2

2008, the drop has picked up again, with a one year high $278 billion plunge in

Q2.

Among the liability components of the Shadow Banking system's credit money

abstractions, we look at:

- Money Market Mutual Funds: at $2.6 trillion, a decline of $41.6 billion Q/Q

- GSE and Agency Paper: at $6.5 trillion, a decline of $73.8 billion Q/Q

- ABS Issuers At $2.2 trillion, a decline of $80.4 billion Q/Q

- Repos at $1.2 trillion, a decline of $49 billion Q/Q

- Open Market Paper at $1.1 trillion, a decline of $50 billion Q/Q

- and these declines were offset by a tiny increase of $17 billion to $726 billion at Funding Corporations

Altogether, added across this amounts to a massive $278 billion in the second

quarter, and explains why GDP, when the manipulation from the Census Bureau is

eliminated would have probably declined. What is worse is that should this

decline continue without an offset, there will be no economic

growth guaranteed.

So where can said offset come from? Well, just as there is a shadow banking

system, so there is a traditional commercial bank system with listed

liabilities. To be sure, for the duration of collapse in the shadow banking

system, this has been the only offset, although granted one that is not nearly

doing a good enough job. Specifically, total liabilities of Commercial

Banks in Q2 were $13.4 trillion, an increase of $238 billion in the

quarter. Alas, this is nowhere near enough to offset the decline in

Shadow Banking, having grown by "only" $2.6 trillion since Q2 2008, even as

shadow liabilities declined by double this amount. Yet there was a brief saving

grace came in Q1 when the spike in Traditional liabilities more than offset the

drop in Shadow, as the cumulative total rose by $337 billion, the most since

2008. Too bad, however, that adding across these two categories (second chart

below), we once again witnessed a decline in Q2, amounting to $40.1 billion.

This explains not only why QE2 could only do so much, but why GDP growth has

rolled over and is now almost certainly negative.

What is most important to keep in mind, is that Traditional Commercial Bank

assets only grow courtesy of QE. And with Shadow banking continuing to implode,

Commercial Banks have to pick up the slack or else... Which in turn means

Bernanke has to keep pumping reserves. Whether banks use these to lend out, or

to buy shares of Netflix is irrelevant: remember - America, and the entire

developed world, is a credit driven system. Take away credit growth and it is

game over.

Which explains why tomorrow's decision is a formality: Bernanke has no choice

but to continue offsetting the relentless contraction in shadow liabilities,

which as of Q2 collapsed at an annualized rate of over $1

trillion. Incidentally this, +$1, is the very minimum that Bernanke

will have to bring into reserve circulation to offset the relentless

deleveraging of the once biggest contributor to American growth, which

ironically is now the biggest adverse factor.

That reversion to the mean sure can be a bitch.

Overbought Dow Stocks with Good Yields

These four Dow stocks offer safe, steady yields as well as solid growth

potential, making any of them worthy buys on any pullback.

Stocks finished out last week surprisingly strong, and many of the strongest

stocks were some that offer attractive yields. My weekend scan of the stocks in

the Dow Jones Industrial Average shows that the ten most overbought stocks all

have attractive yields. That is not surprising given the current uncertain

investment environment and the high degree of pessimism about the stock

market.

I have listed the ten stocks whose weekly close was the nearest to their

weekly Starc+ bands. For example, The Coca Cola Co.

(KO) closed last week at $71.23, which was just 2.6% below the

weekly Starc+ band at $73.07.

Often times the proximity to the weekly

Starc + bands can provide a strong warning signal. NetFlix Inc.

(NFLX) came very close to its weekly Starc+ band in July at $305 and has since dropped over 50%. NFLX closed

last week below its weekly Starc- band, suggesting it is now a high-risk time to

sell. The weekend announcement that NFLX is planning to split up their business

may stem the stock’s slide.

Stocks are under pressure in early trading, suggesting we may see a pullback

before the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting on Wednesday. This

should lower the overbought status of some of these Dow stocks.

Chart Analysis:

The Coca Cola Co. (KO) closed last week near the three-week highs at $71.77. This

stock was noted in early September as one of the few Dow stocks that was higher

for the year.

- There is first support in the $70 area with more important at $67.40-$69. There is trend line support (line a) and the weekly Starc- band in the $63.76-$64.50 area

- The weekly relative performance, or RS analysis, moved through major resistance in July (line b) and has been in a clear uptrend since the 2010 lows

- Volume was higher last week and the weekly on-balance volume (OBV) has turned up after testing its weighted moving average (WMA)

- The daily OBV (not shown) is still clearly positive and is well above its rising weighted moving average

Microsoft Corp (MSFT) has rallied 14% from the August lows at $23.79 and the

weekly downtrend, line d, is now at $27.75. There is additional resistance at

$29.46 with the mid-2010 highs at $31.58.

- The two-year downtrend in the RS analysis, line f, was finally overcome in July, which is an encouraging sign. The RS is now at strong resistance, so the next month or so will be important

- The weekly OBV is still negative, and even though volume increased last week, it is still below its weighted moving average and the downtrend, line g

- The daily OBV (not shown) is positive but still below major resistance

- Initial support now stands at $26-$26.40 with further support at $25.20. There is key support, line e, in the $23.76-$24.25 area

Procter & Gamble

(PG) is a regular on most lists of “safe-haven” stocks, as it

is the ultimate consumer staples company. Of the top four overbought stocks, it

has the second-highest yield at 3.30%. PG closed strongly last week above the

prior three-week highs.

- There is strong resistance on the weekly chart in the $66.27-$67.80 area

- The RS was in a well-established downtrend, line e, from June 2010 until May 2011 when the downtrend, line a, was overcome

- The RS moved through resistance (line b) in the past month, which completes the bottom formation

- The weekly OBV is still negative, as it is slightly below its weighted moving average and further below its downtrend, line c

- The daily OBV (not shown) looks strong, but PG is very close to its daily Starc+ band

Intel Corp. (INTC) has rallied 14.6% from the early-September lows at

$19.16. The close was at the daily Starc+ band with the weekly Starc+ band at

$22.78. There is major chart resistance now in the $23.25-$24 area.

- The RS has just overcome year-long resistance, line e, which may be a sign that INTC is finally ready to break out of its trading range

- The weekly OBV has turned up from support at line g but is still below its weighted moving average

- There is now a band of good support in the $20.60-$21.20 area with major support in the $19-$19.20 area, line d

What It Means: These four Dow stocks all have higher yields

than the ten-year Treasury, which yields just over 2%. The yield of these

stocks, plus their growth potential, makes them much more appealing, even in

this difficult market.

The proximity to the weekly Starc+ bands does not favor chasing these stocks

at current levels, however. Instead, wait for a pullback or at least for some

consolidation before buying. The two technology stocks, MSFT and INTC, appear

the most attractive.

How to Profit: For Microsoft Corp. (MSFT), buy at $25.78 with a stop at $23.42 (risk of approx.

9.1%). On a move above $28.50, raise the stop to $24.76.

For Intel Corp. (INTC), buy at $20.68 with a stop at $18.72 (risk of approx.

9.1%). On a move above $23.45, raise the stop to $19.80.

Etichette:

Analysis Technic,

analysis technic article,

articles,

Stocks

Res Politica versus Res Economica

By John Mauldin

Today’s Outside the Box is the latest chapter in my ongoing discussion with

Dr. Woody Brock on the rationale of the politics of economics. In this essay,

Woody explains how political science has taken a back seat to economics, and how

to redress the imbalance we find today between what he terms “Res Politica” (the

rule of politics) and “Res Economica” (the rule of economics or money). Where

the rubber meets the road here is that our important economic decisions are

increasingly being made by politicians (who are not particularly well-schooled

in either economics or political science), with consequences that are likely to

be dangerous. You will have to put on your thinking cap, but this will provide

you with some real insights and food for thought.

Woody is one of the best “big-picture” economic theoreticians of our time,

and that’s why I treasure the times we get to talk (or rather I get to “sit in

“school” and learn), and have invited him to speak at our annual conference. He

has already committed for next year, so save the dates: May 2-4 in La Jolla. In

the meantime, you can find more of Woody’s thinking at his company’s site, Strategic Economic Decisions.

(For the record, this is the first OTB I have sent from my iPad.)

Your hoping the politicians are listening analyst,

John Mauldin, Editor

Outside the Box

Outside the Box

RES POLITICA versus RES ECONOMICA

Why Economics Must Yield to

Politics as the Paradigm of Tomorrow

By: Horace W. Brock, Ph.D. President Strategic Economic Decisions, Inc., http://www.SEDinc.com

Author’s Note: We are living in the age of

economists, the Age of Larry Summers as it were. But economists have less and

less to say about the important issues of our time. This is because these issues

are political – indeed political philosophical – in nature, not economic. Yet

“political science” is rightly regarded as a second rate discipline, and

political philosophy has morphed into the History of Political Thought.

This essay explains why political science became irrelevant, and how to

redress today’s imbalance between Res Politica and Res Economica.

A. Economics Imperialism and its Origins

The phrase “economics imperialism” has circulated for nearly three decades.

It refers to the reality that, of all the social sciences, economics has emerged

as the most relevant, most useful, and most rigorous discipline. Its perspective

on social behavior and its analytic methods have invaded every facet of

sociology, political science, and social psychology. The success of such books

as “Freakonomics” is proof of precisely this point, as has been trumpeted by its

author Steven Levitt. Finally, if any further proof of economics hegemony is

needed, just consider the surging enrollments in economics and finance courses

at major universities worldwide, a surge that is well known to have caught

university administrators off guard.

The same phenomenon is true in public policy analysis. There was a time when

the cabinet of the US president was dominated by lawyers, or political

scientists and theorists, but that is no longer the case. We are living in an

age when economists such as Martin Feldstein or Lawrence Summers or Alan

Greenspan dominate policy discussions. With their well-honed analytical skills

(lacking in other fields), they sound off with credibility on any number of

topics, and often have the last word.

There are four reasons why all this has happened. First, the

discipline of economics is indeed highly analytical and rigorous, and this

imparts credibility to it. It can explain phenomena, and also (to some extent)

abet forecasting the future.

Second, the analytics of economics are not mere abstractions, but

are transformed into testable models via the linkage between economics and

econometrics. In an age when the “objectivity” of analysis is prized (and indeed

required by the press), it sure helps a policy maker to trot out extensive

statistical back-up for his case. The fact that most people confronting

econometric evidence have no way of knowing whether the underlying statistical

methodology is valid does not change this reality.

Third, economics was the first discipline to put central emphasis on

the concept of “incentives.” When they make decisions, consumers, producers, and

investors respond to given incentives. This point is extremely important for two

reasons: (i) the concept of “incentive structure compatibility”

is arguably the most important concept ever set forth in the history of

analytical social science; and (ii) incentives can be changed

by government policy. This second point has permitted economics to be linked to

public policy in a very compelling manner: By knowing the consequences of

changing incentives, a politician can much better predict the outcome of a

change in policy, and thus identify a better policy.

Fourth, beginning students of economics are presented with a

timeless and powerful analytical model that is as compelling to economics as is

the Law of Gravity to physics: The Law of Supply and Demand. Imagine economics

without this model! Moreover, no matter how far students progress in their

studies, they never deviate far from the model of market equilibration via the

price system.

The Contrasting Failure of Political Science: Now contrast

this plethora of selling points to the dismal state of political science today.

To begin with, there is no organizing paradigm or “model” of any kind. The field

is often described as “mush.” At its best, the discipline serves up rules of

thumb about alternative voting procedures and their relative desirability.

Issues of incentives and incentive structure incompatibility are suppressed,

even though they are as important in politics as in economics. Worse yet, the

fundamental paradigm of politics is largely side‐stepped, namely “Politics: Who

gets What, When, How,” as set forth in 1935 by Harold Laswell. That is, the

all-important paradigm of politics as multilateral bargaining between

interest groups is absent from the pages of most political science

textbooks.

For reasons we are about to see, these deficiencies of contemporary political

science must be remedied. In particular, we need a hard-core analytical model as

compelling to Res Politica as the Law of Supply and Demand is to

Res Economica.

B. Why the Paradigm of Economics No Longer Suffices

It is time to take a leaf from Aristotle, who correctly recognized that

political science is the master discipline—not economics. Here are

several reasons why:

First, by reviewing the meaning of “true capitalism” it is clear

that our cherished paradigm of free market economics is completely dependent

upon the assumptions of the rule of law, of unbribable judges, of sanctity of

contract, and of transparency. Put bluntly: Proper political institutions are a

necessary condition for the virtues of a free market system to deliver

the outcome society wants. They come first. They are not an after-thought.

Second, the ability of a free market capitalist system to deliver

the goods requires much more than the basic institutional set-up just described.

Specifically, whenever issues of “public goods,” “externalities,” or “imperfect

competition” arise, impacted interest groups must determine via multilateral

bargaining exactly what gets provided, and who is to pay how much of the

bill in the process. Moreover, in a global context, issues of how to cope with

misaligned currencies, vast trade deficits, and theft of intellectual property

rights will only be resolved politically via multilateral bargaining

between myriad interest groups. This is part and parcel of a

well-functioning capitalist system.

Third, we are living in a world where the price, quantity, and

allocation of important commodities like oil were once determined by a free

market. But they no longer are. We are now witnessing the ongoing and dangerous

“politicization” of the oil, gas, copper, and other markets. The same is true in

the case of multilateral bargaining over “intellectual property

rights.”

Fourth and more broadly, most of the important issues that could

stymie future world growth and precipitate war remain quintessentially political

in nature. For starters: Who gets how much water at what price? Who will pay how

much for global warming? How much will tomorrow’s youth be taxed to pay for the

elderly? Which nations will be “allowed” to go nuclear? And how will rival

claims in the Middle East eventually get sorted out?

In short, our future depends upon success in politics—that is, in the quality

of future “governance” to utilize a preferable term. But what do we mean by

“success in governance?” Is there a yardstick equivalent in politics to

“resource allocation efficiency” in economics? More broadly, is there an

organizing paradigm or model that could prove as useful to res politica

in the future as the Law of Supply and Demand has proven useful to res

economica in the past? Happily, there is. Yet this model is completely

unknown to most political scientists and philosophers. This must change.

C. The Possibility of the Hegemony of Political Science

– The

Nash-Harsanyi-Selten Pluralistic Bargaining Model –

The model in question is known as the Nash-Harsanyi-Selten (NHS) model of

multilateral bargaining. It is one of the accomplishments that earned all three

game theorists the only triple Nobel Prize awarded in economics (1994).

Moreover, this model is one of the analytical marvels in the history of

analytical science, and indeed of all science. (The fundamental paper in this

regard is “A Simplified Bargaining Model for the n-Person

Cooperative Game,” by John C. Harsanyi, International Economic Review,

4, pp. 194-220, 1963. This paper synthesizes and unifies the different theories

of Nash, Selten, and Shapley into a coherent whole.) Before its development

during the period of 1950–1965, concepts like “democratic pluralism,”

“bargaining equilibrium,” “balance of power,” and “power” itself were

problematically elastic concepts that lacked precise meaning. Additionally,

without this model, the notion of relative bargaining ability could not be

defined. For absent a model predicting an optimal bargaining equilibrium between

symmetrically rational players, the degree to which one player bargained

better than another could not be determined. By extension, it was

impossible to assess the relative competence of different governments in

striking bargains on behalf of their citizens without the yardstick such a model

made possible.

The Building Blocks of the Model: The building blocks of the

logic are starkly simple: (i) a set of n

individual players; (ii) the set of

2n–2 possible coalitions that could form and oppose

one another (e.g., the environmentalist lobby versus the lumber industry);

(iii) the set of all n(n‐1)/2 possible pairs

of players that could come face to face with each other in any number of

coalitions that might include them both; and (iv) the different

resources of each individual player and each coalition—including resources each

could use to threaten the others.

The Bargaining Logic Utilized to Arrive at a Rational Compromise:

In Stage 1 of the two-stage bargaining game, the various coalitions

form and determine their best threat strategies to be utilized against their

complementary coalitions in the event that no compromise ends up being reached,

and the players fall back on playing their threat strategies (e.g., labor goes

out on strike and/or management eliminates their jobs). In Stage 2, the

all-player coalition of all n members forms, and its members

determine how to allocate the gains to each player (above his threat

payoff) that mutual cooperation makes possible.

The basic point is that, since everyone (with suitable side‐payments) can end

up better off by compromising rather than receiving their non-cooperative threat

payoff, they have an incentive to reach a compromise. This is, of

course, the hallmark of all social life as we know it. In the NHS model, the

compromise that rational players arrive at will be that agreement that equalizes

the “risk limits” of every player, as John Harsanyi first pointed out. The

interested reader is referred to a footnote that explains this remarkable result

in more depth. (During the process of bargaining, each player starts off

demanding more than he knows he will end up getting. As the game goes on, each

player thus makes compromises so as to reduce the risk that others players say,

“Screw you—we shall play our threat strategy against you!” Where does this

process stop? What is the “sticking point” beyond which rational players will

not make further concessions? It occurs at the point when the utility

losses from making a further concession exactly equal the utility value of the

reduction in risk that results from making the concession. [Mathematically, this

point happens to be the outcome with the property that it maximizes the

arithmetic product of the utility gains of the players above their threat

payoffs. The product—not the sum!])

Market-based economic exchange is a very simple form of a bargaining game in

which a consumer’s only threat strategy is simply not to buy a given product at

the price offered. In more general political contexts, threats must be

determined on the basis of how much damage a given coalition S

(or single player) can do to its opposing coalition R

net of the cost to itself S from carrying out

its threat—relative to the damage the opposing coalition R can

do to it S net of the cost to itself R

from carrying out its threat. The logic is subtle: What

matters is relative threat power.

The Remarkable Power of this Framework: There are four ways

in which the NHS model is extremely powerful:

1. It Offers a Simple Graphical

Representation of Politics: As stressed above, political science

will never be a “science,” much less a successor to economics as a dominant

paradigm without an intuitively appealing graphical model, such as that of

intersecting supply and demand curves in economics. Happily, there does exist an

analogous diagrammatic representation of bargaining. It is shown in the Appendix

to this essay below.

2. It Incorporates the Right Mix of “Cooperative”

and “Non‐Cooperative” Game Theory: In searching for the right paradigm

with which to make sense of strategic interaction, game theorists during past

decades believed that they needed to choose between two very different kinds of

games: non-cooperative versus cooperative games. In the former case, emphasis is

placed on the requirement that every player individually adopts a

strategy that is optimal against every other individual’s strategy. This

requirement must hold symmetrically for every player. Moreover, there are no

coalitions in non-cooperative games.

In this paradigm, cooperation between people of the kind that arises in

multilateral bargaining is oddly absent. The best, and indeed most celebrated,

example of such a game is the Prisoner’s Dilemma in which, since neither

prisoner can get together with the other and make a binding agreement not to

tattle on the other, no gains from cooperation are possible. In this

pathological case, the solution of the game (the non-cooperative Nash

equilibrium) is for each prisoner in isolation to tattle on the other. The

result: Each serves a much longer term in prison than would have been the case

could they have communicated and agreed not to tattle.

Regrettably, this non-cooperative paradigm has dominated game theory

for the past two decades. Previously, the cooperative paradigm had been

dominant. In this latter case, the perspective is one in which players enter

into groups for the purposes of adopting coordinated strategies that end up

leaving everyone better off. In other words, they utilize outright bargaining to

arrive at an optimal division of the spoils resulting from cooperation.

Cooperation is central. The problem with most of these models was that they gave

no play to the phenomenon whereby players adopt credible threats against one

another as a prelude to the “final settlement.” In short, if classical

non-cooperative game theory suffered from ignoring the gains from cooperation,

classical cooperative theory failed to incorporate the non-cooperative aspects

of human relations (threat-making in particular) in a proper manner.

It is one of the great virtues of the NHS model that it fully integrates

both aspects of politics into a coherent model: The non-cooperative

posturing (“If I don’t get my way, I’ll see that you pay dearly”) is integrated

with the cooperative process of arriving at a final distribution of the proceeds

from cooperation. It was John Harsanyi, who in 1963 provided a complete

unification along these lines in games with n>2 players, and

demonstrated mathematically how the two principal dimensions of bargaining (the

threat game versus the cooperative game) are logically interdependent:

One cannot be solved without solving the other. (Specifically, the equations

characterizing the bargaining equilibrium are a set of simultaneous nonlinear

equations, as is true of the general model of supply and demand in economics

(Arrow-Debreu general equilibrium theory), and in many models within physics and

biology.)

3. It Provides of a Yardstick for Measuring Bargaining Ability and

thus Political Competence: As we suggested above, in the absence of a

compelling definition of a rational bargaining outcome, it is difficult to say

whether a given party bargained “competently” or “incompetently.” By extension,

with no yardstick in hand, there can be little accountability by government to

its citizenry regarding the quality of bargains it strikes, whether implicitly

or explicitly. Happily, the NHS model provides precisely the missing yardstick.

We will demonstrate this qualitatively in Section D just below where we apply

bargaining logic to the difficult problem of negotiating with China.

4. It Offers a Unifying Framework for the Moral Tripos of

Politics, Economics, and Ethics: We have already cited several of the

reasons for the primacy of politics over economics (e.g., the importance of the

rule of law as a precursor of market economies, as well as the bargaining that

arises in dealing with market externalities, with public goods, with imperfect

competition, and with trade and currency values). But when the NHS perspective

is introduced, the potential hegemony of politics far transcends these issues of

economics.

The physicist Mendel Sachs has recently identified a single truly unified

field theory in physics from which all manifestations of matter

(quantum phenomena, gravity, and electromagnetism) can be derived—just as

Einstein always predicted would be the case (Sachs, M. Quantum Mechanics and

Gravity, Springer Verlag, 2004). Analogously, and remarkably, it turns out

that the NHS bargaining model can provide a unified framework for several

disciplines within social science. In particular, the model can be “extended” in

many different directions to re-derive the most serious theories now existing of

interest group politics and of unbiased political representation

and of perfectly competitive market economies and of the moral

philosophical theory of Distributive Justice (astonishingly, “To Each according

to His Contribution” and “To Each According to his Needs” can both be

derived from the NHS model). The author is now writing a book on this

subject.

D. An Application of the NHS Bargaining Model

– Case Study of How to

Redress China’s Role in Global Imbalances –

The Consensus: In recent years and especially during recent

months, the economics establishment has come down hard against those who believe

it is time to retaliate against China—a view increasingly proposed by Democratic

legislators and candidates for the US presidency. Whether it be Paul Krugman,

Martin Wolf, David Hale, the editors of the New York Times or the

Wall Street Journal or the Financial Times, the consensus of

the intelligentsia is: “Neither the US nor the West, more broadly, should fall

for the populist trap of protectionism. China needs time to develop, and must be

encouraged to undertake a gradual approach to currency revaluation and reform in

general.”

Other commentators go further and suggest that both parties are

gaining from today’s status quo: “The US obtains cheap financing of its current

account deficit, as well as products whose low Wal-Mart prices have kept

inflation in check, whereas China obtains the huge market that it needs for its

export machine.” This seductive argument runs afoul of the “no Free Lunch”

theorem in economics. In the present case, this translates into the reality that

the US will end up $4 trillion in debt to China for all these goodies—a debt we

will pass on to our children, in addition to trillions of domestic debt.

The Fallacious Reasoning Underlying the Consensus View:

Given China’s clearly undervalued currency and skyrocketing global

trade surplus, what is the origin of the view that we must not fall prey to

protectionism? Its origin is very interesting, and is central to the change of

paradigm that we are proposing in this essay. The principal justification of the

consensus is that, should we retaliate against Chinese policies via the

imposition of tariffs, a trade war would result. For example, as a lead New

York Times editorial of August 13, 2007 stated: “We have consistently

argued against such punitive legislation, which could harm America’s economy by

unleashing a trade war.”

An Alternative and More Constructive Perspective:

But is this, in fact, the case? Need US legislation unleash a

trade war? The answer to both questions is “No,” once a proper bargaining

perspective is adopted. More specifically, today’s consensus is based upon the

widespread assumption that resolving trade frictions constitutes a

non-cooperative game. The logic that, if we do anything to upset China,

they should and will retaliate, is taken from the logic of non-cooperative games

like the Prisoner’s Dilemma. But this is not the correct logic, especially since

the very concept of economic exchange is cooperative in nature. When I

sell to you and you buy from me, we must both be gaining or else the trade would

not have occurred. Thus, we need to adopt a cooperative game perspective—but one

in which the role of mutual threats and recriminations assume their proper toll.

This is exactly where the NHS perspective rises to the fore.

Here is what this perspective says regarding bargaining with China at

present:

First, recognize that the concept of retaliation as being

“protectionist” is nonsensical when China (and Asia, more broadly) admits to

having been mercantilist for decades. We reiterate a point made in previous

reports: Under true capitalism, there could not exist a $2 trillion cumulative

US trade deficit with China, much less a cumulative $4 trillion deficit with

Asia as a whole. For under true capitalism (no mercantilism, open