by Liu Mingkang

HONG KONG – When the US investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed five years ago, emerging-market economies did not hold many of the toxic financial assets – mainly American subprime mortgages – that fueled the subsequent global financial crisis. But they were deeply affected by the drop in world trade, which recorded a peak-to-trough decline of at least 15%, with trade finance also contracting sharply, owing to a shortage of dollar liquidity. Have policymakers responded appropriately since then?

Illustration by Paul Lachine

Soon after the crisis erupted, the G-20 countries embraced massive stimulus packages, unconventional monetary policies in the advanced economies, and major institutional efforts, such as the Dodd-Frank financial-reform legislation in the United States and the Basel III initiative to strengthen banking standards. China’s ¥4 trillion stimulus package, unveiled in November 2008, restored confidence in global commodity markets. Led by strong Chinese growth, emerging markets stabilized.

Since 2009, quantitative easing (QE) by the US Federal Reserve has resulted in record-low interest rates around the world. But, while the resulting surge in capital flows to emerging markets stimulated economic growth, it also inflated asset bubbles.

Now, with the Fed publicly considering an end to its massive, open-ended purchases of long-term securities and foreign capital fleeing home from emerging markets, many fear that Asia’s economies could come crashing down, as they did in the late 1990’s. Leverage in some emerging markets’ household and corporate sectors has reached record levels. China’s annual economic growth has slowed to around 7.5%, while Indonesia and India – and, outside Asia, Brazil and South Africa – are experiencing sharp downward pressure on their exchange rates.

Moreover, there has been no major reform of the global financial architecture. China’s renminbi is internationalizing, but its share of global payments remains relatively small, with the dollar retaining its role as the world’s main reserve currency. And, while regulatory reform is progressing, its effectiveness in addressing the weaknesses exposed by the global financial crisis will depend not only on the new rules that emerge, but also on the consistency and quality of their implementation.

There has been commendable progress on the Basel 3 capital requirements for banks, with 25 of 27 Basel Committee members having issued final rules. Likewise, the impact of regulatory changes resulting from major legislation and policy directives in the United States, Europe, and the United Kingdom on banking, insurance, financial-transaction taxes, anti-money laundering, and cyber-space is likely to be substantial.

Although rules on shadow-banking have yet to be formulated, another problem exposed by the crisis has abated: America’s external deficit has shrunk to a much more manageable 2-3% of GDP, accompanied by drops in the surpluses run by Japan and China. Global trade rebalancing has arrived.

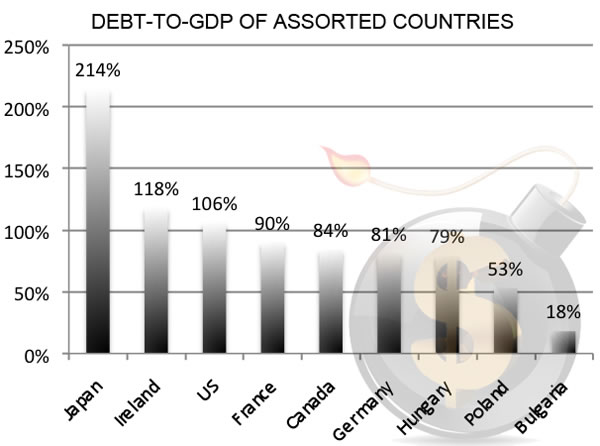

Still, fiscal conditions in the advanced economies remain unsustainable, with many OECD members’ debt levels hovering around 100% of GDP. Japan, which has one of the world’s highest debt/GDP ratios, currently well over 200%, is engaging in a risky experiment with further monetary stimulus to try to target 2% annual inflation. In many advanced economies, both monetary and fiscal policies have reached the limits of their effectiveness.

The key questions now are whether global economic growth is self-sustaining without QE, whether emerging markets’ output will continue to rise strongly, albeit at a slower pace, and whether current global financial-reform efforts will be sufficient to prevent another crisis in emerging markets.

Given the high degree of trade and financial globalization that now characterizes the world economy, there is no doubt that the slowdown in the advanced economies, which account for two-thirds of global GDP, will undermine emerging-country growth. Indeed, the threat to withdraw QE is already having an enormous impact on emerging economies’ asset markets. As real interest rates and risk premia begin to rise, the level of global trade and investment will decline.

In the coming years, emerging markets will most likely struggle with implementation of global financial regulatory standards, which apply mostly to more sophisticated financial markets. They will also confront a rapidly changing external environment and a growing need to manage capital flows more effectively, which will require much closer coordination between central banks and financial regulators.

Indeed, perhaps the most important lesson learned in the aftermath of the collapse of Lehman Brothers is that we can no longer afford to examine problems in terms of individual institutions and from regulatory “silos.” The global economy’s high degree of interconnectivity, interdependence, and complex feedback mechanisms imply that one weak hub can bring down the entire system.

In other words, the world needs a systemic approach to deal with systemic risks and system failures. Unfortunately, there may be little hope of strengthening global financial governance as long as implementation and enforcement of rules remain at the national level.

Like other emerging markets, China is committed to financial stability and playing its role in reforming the global financial system. China was one of the first countries to sign up to the Basel 3 standards, and further renminbi internationalization will be implemented in a prudent and pragmatic manner. Domestic financial reforms will focus on strengthening policy coordination and moving toward market-determined interest rates and exchange-rate flexibility.

All of these steps will contribute to sustainable domestic growth and a more stable global financial system. Other major emerging economies’ policymakers would be wise to act with the same purpose in mind.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

.jpg)