"I'll Be Waiting"

He broke your heart

He took your soul You hurt inside 'Cause there's a hole You need some time To be alone Then you will find What you've always known I'm the one who really loves you baby I've been knocking at your door As long as I'm living I'll be waiting As long as I'm breathing I'll be there Whenever you call me I'll be waiting Whenever you need me I'll be there I've seen you cry Into the night I feel your pain Can I make it right I realize there's no end in sight Yet still I wait For you to see the light I'm the one who really loves you baby I can't take it anymore As long as I'm living I'll be waiting As long as I'm breathing I'll be there Whenever you call me I'll be waiting Whenever you need me I'll be there You are the only one I've ever known That makes me feel this way Girl you are my own I want to be with you Until we're old You've got the love you need right in front of you Please come home As long as I'm living I'll be waiting As long as I'm breathing I'll be there Whenever you call me I'll be waiting Whenever you need me I'll be there... |

Saturday, April 12, 2014

Lenny Kravitz - I'll Be Waiting

Control your risk with simple and winning rules – SuperStocks trading signals for 14 April

| Super Stocks Trading Signals Report | |

| Latest Free Trading Alerts for 14 April | Download Historical Results |

| Open position value at 11 April $ 2,528.22 | 2014 P/L +3.35% |

| Mixed long/short open position | In true signal service, attachments reports are sent to customers also via email, in the evening after the markets close. Those who wish to receive them during the demo, please send me their email address. |

| We are happy to offer free signal service for Super Stocks until the end of March | Please send me your email address so I can invite you on my server to do the demo. Mail me to take the offer and start the free service until the end of March michele.giardina@quantusnews.com |

| Material in this post does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation and do not constitute solicitation to public savings. Operate with any financial instrument is safe, even higher if working on derivatives. Be sure to operate only with capital that you can lose. Past performance of the methods described on this blog do not constitute any guarantee for future earnings. The reader should be held responsible for the risks of their investments and for making use of the information contained in the pages of this blog. Trading Weeks should not be considered in any way responsible for any financial losses suffered by the user of the information contained on this blog. |

All Hail The Draghi Put: The Global Bond Market Is Now Well And Truly Broken

| The evil of modern central banking can nowhere better be seen than in this week’s mad stampede into $4 billion of Greek bonds. The fact is, Greece is not credit-worthy at nearly any coupon yield, but most certainly not at the 4.75% sticker that was attached to the offering. After a 20% contraction, the Greek economy has been literally eviscerated—with not much left except tourism, yogurt plants and a 27% unemployment rate. It has an impossible debt-to-GDP ratio of 170 percent and, worse still, almost all of that debt is owned by EC institutions and the IMF. That is, this week’s “winners” stand in line behind the “bail-you-in-first-brigade” that will find some way to crush private investors—-English law indentures or not—when repayment of their own tower of loans comes into question. And the claim that Greece’s fiscal affairs have turned for the better is really preposterous. Like Italy and some of the other PIGS, the Greek government has discovered the trick of off-balance sheet financing by stiffing its vendors. The backlog of “payables” to pharmacies, hospitals, doctors, garbage haulers, road maintenance vendors and countless more, along with deep arrearages in payments to pensioners and other transfer payment beneficiaries, has been manipulated by the finance ministry and their Brussels overseers to a fare-thee-well, and now totals in the tens of billions. This has created the impression, of course, that Greece’s budget is on the mend; its actually on the road to yet another political crisis owing to the parched liquidity among vendors and the precarious finances of beneficiaries. And that’s to say nothing of the absolute fracturing of the Greek body politic, where its current lame government survives by kicking enough recalcitrants out of the Parliament, as may be needed, to clear the next Brussels demanded action with one vote to spare. In short, Greek sovereign risk cannot be even calculated by the market because it essentially has no functioning sovereign. But none of this matters, of course, because the howling pack of money managers who scooped up the Greek debt at an oversubscribed rate of 5X were not pricing the non-credit of the former Greek state, but the promises of Mario Draghi—-the Goldman Sachs plenipotentiary temporarily seconded to Frankfurt. Even the New York Times figured out that this week’s ballyhooed “return to the market” was a complete farce:

They even found one of the remaining sane spokesman for the EC apparatus to clear the air and verify that the offering had nothing to do with “price discovery”—-the ostensible purpose of capital markets:

Besides vast mis-pricing and mis-allocation of capital, central bank puts also drastically impair even the daily vocabulary and discourse in the markets—rudiments that are essential to effective and honest price discovery. After noting what is the sheer lunacy of the “Draghi put”, and that the herd of fast money traders which chase it have driven the yield on Spanish 5-year debt below that of US Treasuries, the NYT found one money manager who wasn’t drinking the Kool-Aid. Fadi Zaher, the head of bonds and currencies at Kleinwort Benson, said his group had stayed on the sidelines due to “lingering concerns about the country’s poor economic health and its mountain of debt”. Still, after noting that “there is euphoria right now over the Euro area” and that the euphoria is spilling over to Greece, Mr.Zaher concluded by saying: “We are cautiously optimistic about the story, but looking over the longer term we are very, very cautious about it.” Well, that is the equivalent of an analyst “hold” rating, but the vocabulary speaks for itself. The crush of momentum trading and the herd kiting of central banks is so overwhelming that even a professional skeptic could only muster a “very, very cautious” utterance. In truth, the better utterance would have been a “sell, sell. sell”. Yet the very worst evil of monetary central planning is that it enables clueless politicians to believe in their own fiscal fairy tales, and to persist in the ritual can-kicking that is the scourge of central bank intoxicated politicians everywhere. In the context of its shattered economy, the Greek budget is a house of cards. Still, its current leaders, whose tenure is precarious by the day, get their turn in the spotlight to issue utterly specious pettifoggery:

|

This Is Not A “Healthy Correction”: The Mother Of All Financial Bubbles Is Beginning To Crack

| Wolf Richter is one of the most astute observers of our bubble-ridden/central bank perverted financial scene around. His blog called Testosterone Pit is a daily “must read” and more than that: its posts are succinct, spritely, fact-based, conclusionary and cover the global map with special insight on those debt ridden houses of cards on the other side of the Pacific—-Japan and China. Wolf today issued a timely warning. Next week we will be told by Wall Street stock peddlers that what are just having a healthy correction and that it will soon be time to “buy the dip”. Don’t believe them. We are perched precariously at the top of one of the greatest financial bubbles ever because it is global—-the handiwork of world-wide central bank driven credit expansion and drastic interest rate repression. Just recall some of the numbers. At the turn of the century, the US had about $25 trillion of credit market debt outstanding; now it is pushing $60 trillion. About 14 years ago, China had debt of $1 trillion; now its nearly $25 trillion. And similar credit explosions occurred in much of the rest of the world. It was all central bank enabled, and it caused world wide investment booms and asset inflations which defy every law of sound money and economics, and which cannot be sustained indefinitely. The bottom line of those destructive policies is that “cap rates” are artificially low and so their reciprocal, asset values, are enormously inflated. Likewise, nearly zero money market interest rates in virtually every major economy of the world have fueled the most fantastic expansion of “carry trades” ever imagined. As I have frequently pointed out, the short-term market for repo and other wholesale funding represents the cost of goods (COGS) for financial gamblers; its what they use to fund their speculations in higher yielding currencies, corporate debt, equities, and every manner of derivatives and OTC concoctions that Wall Street trading desks can engineer. So when the central banks drive the money market rates to just 5-50 bps, they are offering ZERO-COGS to speculators. This is a massive incentive to bid up the price of anything that has a yield north of 50 basis points or a short-run appreciation prospect of the same—in order to capture the spread. This is what has turned the so-called capital markets of the world into dangerous casinos. This is what led speculators this week to gorge on $4 billion in Greek debt carrying the lunatic coupon of just 4.75%. The latter is not even a remotely plausible pricing of the risk of a government with a 170% debt to GDP ratio—- sitting atop an eviscerated economy that has shrunk by more than 20% and has nothing much left except tourism, yogurt plants and a 27% unemployment rate. Instead, it evidences the fast money traders who swooped in to buy a 475 bp coupon funded by free money from the central banks, and who did so in the confidence that the ECB will do “whatever it takes” to prop up the price of member country sovereign debt. Needless to say, the minute that the millions of gamblers who have been enabled by the ZERO-COGS gift of central banks loose confidence in their ability to prop up asset values, the panic will set in. Then a great dumping stampede will start. It will be the mother of all margin calls—-a repeat of the dumping panic on Wall Street that occurred in September 2008 when toxic mortgage securities which had been funded by overnight repo were forced into fire sales by wholesale lenders refusing to roll their repo. Only this one will be much grander because the carry trades have gone more global then ever before. Even pig farmers in China have their sties loaded with copper because through a roundabout trade it can be repo’d for cash. Indeed, the global financial system is land-mined with time-bombs–some hidden and others transparent. But what is certain is that when huge distortions like the newly booming market for dollar-denominated junk bonds being issued by EM companies increasingly parched for cash craters, there will be a ricocheting chain reaction that will spread far and wide. As they might have said back in the day on Hill Street Blues “don’t go out there, its too dangerous”. Below, Wolf Richter reminds us of why. By Wolf Richter At The Testosterone Pit

|

SPY Trends and Influencers April 12, 2014

by Greg Harmon

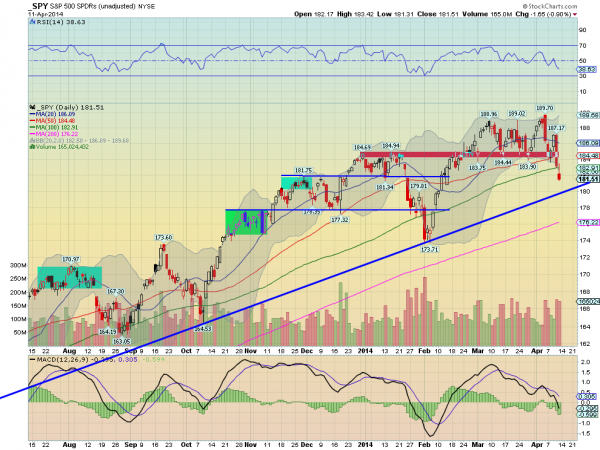

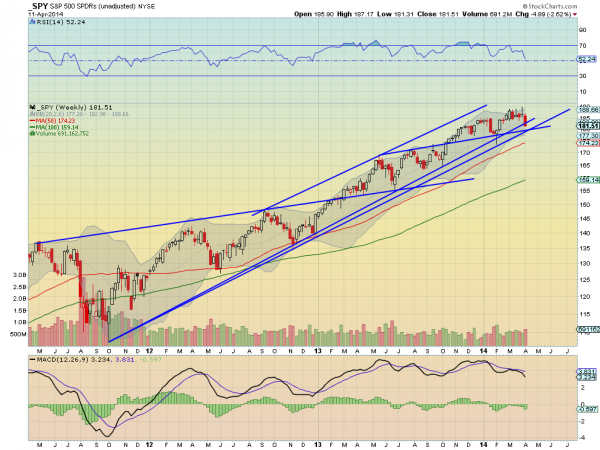

| Last week’s review of the macro market indicators suggested, moving into the next week that equity markets continued to look weak. Elsewhere looked for Gold ($GLD) to move higher with Crude Oil ($USO) in the short term. The US Dollar Index ($UUP) and US Treasuries ($TLT) were also biased to the upside with a chance that Treasuries just churn their wheels sideways. The Shanghai Composite ($SSEC) was poised to consolidate in the downtrend while Emerging Markets ($EEM) were biased to the downside in the short run after a strong move higher. Volatility ($VIX) looked to remain subdued keeping the bias higher for the equity index ETF’s $SPY, $IWM and $QQQ, despite the moves lower last week. Their charts did not share the upside optimism in the short run with the SPY the strongest pulling back near support, the IWM next at support but weak and the QQQ looking lower in the short run. The longer view was similar with the SPY the strongest and consolidating while the IWM was at support and the QQQ moving lower. The week played out with Gold continuing higher as Crude Oil moved up as well. The US Dollar moved lower all week before a small bounce Friday while Treasuries marched higher to the previous long tail. The Shanghai Composite moved higher out of consolidation while Emerging Markets finally met some resistance and consolidated. Volatility picked up a bit and closed the week with a wild range Friday. The Equity Index ETF’s all ended lower on the week with Spinning Top indecision candles, and the SPY below the 100 day Simple Moving Average (SMA)for the first time in two months and the IWM a hair from the 200 day SMA a place it has not visited since November 2013. What does this mean for the coming week? Lets look at some charts. As always you can see details of individual charts and more on my StockTwits feed and on chartly.) SPY Daily, $SPY  The SPY started the week falling to support where it had bounced twice before but with the added support of the 50 day SMA. It did bounce again but only for 2 days before resuming the move lower through the 100 day SMA and finishing at 2 month lows. The daily chart shows that there is rising trend support nearby around 180 and with it out of the Bollinger bands some volatility players may start to buy. The RSI though on the daily chart continues to move lower along with the MACD. The weekly chart shows a strong move lower from consolidation through one rising trend line and approaching the cross of two others. It may be time to erase the higher long term trend line. The RSI is falling and near the mid line, so still in the bullish range while the MACD is heading lower. Both support more downside. Support lower comes at 180.25 and 117.75 followed by 174.25 and 174. Below that and the long term uptrend is in jeopardy. Resistance higher stands at 181.80 and 184 followed by 186.75. Continued Downside in the Long Term Uptrend. Heading into the shortened Passover and pre-Easter week the equity markets look to continue lower. Elsewhere look for Gold and Crude Oil to continue their moves higher. The US Dollar Index looks weak and headed lower, but with support nearby while US Treasuries may be ready to break the long consolidation to the upside. The Shanghai Composite and Emerging Markets look strong with a chance that Emerging Markets consolidate for a bit. Volatility looks to remain subdued keeping the bias higher for the equity index ETF’s SPY, IWM and QQQ, but it is biased to the upside and under watch. The equity index ETF’s themselves show no signs of a reversal higher, only a continuation lower. They all still have room to major trend reversal levels but it appears the short term direction is firmly lower. Use this information as you prepare for the coming week and trad’em well. |

Buy these dips and breakouts from depressed prices?

by Chris Kimble

| CLICK ON CHART TO ENLARGE Do you believe in buying the dips? Do you believe in buying breakouts above resistance lines? Do you believe in buying when an asset breaks above a moving average? If the answer is yes to any of these, the above 3-pack might be interest to you. Remember the 3-pack above is inverted... |

Every Central Bank for Itself

By John Mauldin

| Every Central Bank for Itself “Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face.” – Mike Tyson For the last 25 days I’ve been traveling in Argentina and South Africa, two countries whose economies can only be described as fragile, though for very different reasons. Emerging-market countries face a significantly different set of challenges than the developed world does. These challenges are compounded by the rather indifferent policies of developed-world central banks, which are (even if somewhat understandably) entirely self-centered. Argentina has brought its problems upon itself, but South Africa can somewhat justifiably express frustration at the developed world, which, as one emerging-market central bank leader suggests, is engaged in a covert currency war, one where the casualties are the result of unintended consequences. But the effects are nonetheless real if you’re an emerging-market country. While I will write a little more about my experience in South Africa at the end of this letter, first I want to cover the entire emerging-market landscape to give us some context. Full and fair disclosure requires that I give a great deal of credit to my rather brilliant young associate, Worth Wray, who’s helped me pull together a great deal of this letter while I am on the road in a very busy speaking tour here in South Africa for Glacier, a local platform intermediary. They have afforded me the opportunity to meet with a significant number of financial industry participants and local businessman, at all levels of society. It has been a very serious learning experience for me. But more on that later; let’s think now about the problems facing emerging markets in general. Before going into battle, every general has a plan, which immediately begins to change upon contact with the enemy. Everyone has a plan until they get hit… and emerging markets have already taken a couple of punches since May 2013, when Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke first signaled his intent to “taper” his quantitative easing program and thereby incrementally wean the markets off of their steady drip of easy money. It was not too long after that Ben also suggested that he was not responsible for the problems of emerging-market central banks – or any other central bank, for that matter. As my friend Ben Hunt wrote back in late January, Chairman Bernanke turned a single data point into a line during his last months in office, when he decided to taper by exactly $10 billion per month. He established the trend, and now the markets are reacting as if the Fed's exit strategy has officially begun. Whether the FOMC can actually turn the taper into a true exit strategy ultimately depends on how much longer households and businesses must deleverage and how sharply our old-age dependency ratio rises, but markets seem to believe this is the beginning of the end. For now, that’s what matters most. Under Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s leadership, the Fed continues to send a clear message to the rest of the world: Now it really is every central bank for itself. The QE-Induced Bubble Boom in Emerging Markets By trying to shore up their rich-world economies with unconventional policies such as ultra-low rate targets, outright balance sheet expansion, and aggressive forward guidance, major central banks have distorted international real interest rate differentials and forced savers to seek out higher (and far riskier) returns for more than five years. This initiative has fueled enormous overinvestment and capital misallocation – and not just in advanced economies like the United States. As it turns out, the biggest QE-induced imbalances may be in emerging markets, where, even in the face of deteriorating fundamentals, accumulated capital inflows (excluding China) have nearly DOUBLED, from roughly $5 trillion in 2009 to nearly $10 trillion today. After such a dramatic rise in developed-world portfolio allocations and direct lending to emerging markets, developed-world investors now hold roughly one-third of all emerging-market stocks by market capitalization and also about one-third of all outstanding emerging-market bonds. The Fed might as well have aimed its big bazooka right at the emerging world. That’s where a lot of the easy money ran blindly in search of more attractive real interest rates, bolstered by a broadly accepted growth story. The conventional wisdom – a particularly powerful narrative that became commonplace in the media – suggested that emerging markets were, for the first time in a long time, less risky than developed markets, despite their having displayed much higher volatility throughout the past several decades. As a general rule, people believed emerging markets had much lower levels of government debt, much stronger prospects for consumption-led growth, and far more favorable demographics. (They overlooked the fact that crises in the 1980s and 1990s still limited EM borrowing limits until 2009 and ignored the fact that EM consumption is a derivative of demand and investment from the developed world.) Instead of holding traditional safe-haven bonds like US treasuries or German bunds, some strategists (who shall not be named) even suggested that emerging-market government bonds could be the new safe haven in the event of major sovereign debt crises in the developed world. And better yet, it was suggested that denominating these investments in local currencies would provide extra returns over time as EM currencies appreciated against their developed-market peers. Sadly, the conventional wisdom about emerging markets and their currencies was dead wrong. Herd money (typically momentum-based, yield-chasing investors) usually chases growth that has already happened and almost always overstays its welcome. This is the same disappointing boom/bust dynamic that happened in Latin America in the early 1980s and Southeast Asia in the mid-1990s. And this time, it seems the spillover from extreme monetary accommodation in advanced countries has allowed public and private borrowers to leverage well past their natural carrying capacity. Anatomy of a “Balance of Payments” Crisis The lesson is always the same, and it is hard to avoid. Economic miracles are almost always too good to be true. Whether we’re talking about the Italian miracle of the ’50s, the Latin American miracle of the ’80s, the Asian Tiger miracles of the ’90s, or the housing boom in the developed world (the US, Ireland, Spain, et al.) in the ’00s, they all have two things in common: construction (building booms, etc.) and excessive leverage. As a quick aside, does that remind you of anything happening in China these days? Just saying… Broad-based, debt-fueled overinvestment may appear to kick economic growth into overdrive for a while; but eventually disappointing returns and consequent selling lead to investment losses, defaults, and banking panics. And in cases where foreign capital seeking strong growth in already highly valued assets drives the investment boom, the miracle often ends with capital flight and currency collapse. Economists call that dynamic of inflow-induced booms followed by outflow-induced currency crises a “balance of payments cycle,” and it tends to occur in three distinct phases. In the first phase, an economic boom attracts foreign capital, which generally flows toward productive uses and reaps attractive returns from an appreciating currency and rising asset prices. In turn, those profits fuel a self-reinforcing cycle of foreign capital inflows, rising asset prices, and a strengthening currency. In the second phase, the allure of promising recent returns morphs into a growth story and attracts ever-stronger capital inflows – even as the boom begins to fade and the strong currency starts to drag on competitiveness. Capital piles into unproductive uses and fuels overinvestment, overconsumption, or both; so that ever more inefficient economic growth increasingly depends on foreign capital inflows. Eventually, the system becomes so unstable that anything from signs of weak earnings growth to an unanticipated rate hike somewhere else in the world can trigger a shift in sentiment and precipitous capital flight. In the third and final phase, capital flight drives a self-reinforcing cycle of falling asset prices, deteriorating fundamentals, and currency depreciation… which invites more even more capital flight. If this stage is allowed to play out naturally, the currency can fall well below the level required to regain competitiveness, sparking run-away inflation and wrecking the economy as asset prices crash. (To those of you who’ve been reading me for a while, this may sound suspiciously similar to the Minsky cycle we often use to describe the leverage process. If you caught that, you get extra credit.) In order to avoid that worst-case scenario, central bankers often choose to spend their FX reserves or to substantially raise domestic interest rates to defend the currency. Although it comes at great cost to domestic growth, this kind of intervention often helps to stem the outflows… but it cannot correct the core imbalances. The same destructive cycle of capital flight, falling asset prices, falling growth, and currency depreciation can restart without warning and trigger – even years after a close call – an outright currency collapse if the central bank runs out of policy tools. The Taper Reveals What QE Was Hiding That worst case is the looming risk for many emerging markets today, particularly in the externally leveraged “Fragile Five”: Brazil, India, Turkey, Indonesia, and South Africa (where I am as I finish this letter). Together they account for more than $3.3 trillion of the total $10 trillion of developed-country assets currently invested in emerging markets. Not only have those countries amassed a disproportionate share of total inflows to emerging markets, each has its own insidious combination of structural and political obstacles to long-term growth. And their own central banks are seriously constrained in the run-up to national elections between now and October 2014. After a brief reprieve from taper-induced capital flight, the most externally leveraged emerging economies have had some time to breathe easy; but the crisis is far from over. This one, as all such booms and busts do, will end in tears. Although countries like India and Indonesia have taken positive steps toward reducing their external imbalances, real reforms take time; and balance-of-payments episodes will recur until the core imbalances have been resolved. A sudden rise in real interest rates abroad – which could arise purely from a miscue in FOMC forward guidance – could slam a long list of emerging markets simply by reducing the real risk premium over “safe” assets. Even a 200-basis-point move in US rates could create a strong incentive for less productive capital in compromised or overvalued markets to rush for the exits in headlong capital flight. It may sound like an extreme case, but even a moderate rise in real interest rates abroad would be enough to trigger disorderly and destructive currency adjustments across the emerging world. A little over two months ago, I argued that Reserve Bank of India Governor Raghuram Rajan was stepping forward as the unofficial spokesman for an entire group of emerging-market central bankers struggling to manage what he calls “capital-flow-induced fragility.” (I spent several days on a speaking tour with Rajan, and he is a very serious academic and critical thinker. As a central banker, he will be a force to be reckoned with. I wonder how often that marvelously sly sense of humor that I saw will be allowed to come out during the crisis that is brewing in India. I haven’t seen much of it in his last interviews and speeches. This is a man who understands the seriousness of his situation.) Developed-market observers like to criticize emerging-market policymakers first for complaining about excessive capital inflows into their economies and then for throwing a “tantrum” when supposedly unwanted flows slow or start to reverse… but Rajan took that tendency to task in a January 30, 2014, interview with Bloomberg’s Vivek Law. (You can watch Governor Rajan’s January appeal to rich-world investors here. Even if you have already seen it several times, I encourage you to watch it again… and this time play close attention to his body language.) In the real world, Rajan explained, FX volatility can be downright traumatic for emerging markets. We complain when it goes out for the same reason when it goes in. It distorts our economies. And the money coming in made it more difficult for us to do the adjustment which would lead to sustainable growth and prepare for the money going out. You see, the nostrum amongst economists here is "Let the prices adjust and things will be fine. Let the exchange rate move; let the money flow out; and you will figure it out. That is often a reasonable prescription for an economy that has its fundamentals, as well as its institutions, well-anchored. But when those aren't anchored, what happens is the volatility feeds on itself. Exchange rates fall. Stop loss limits are hit. More selling takes place. Then some firms get into difficulty because they have unhedged exposures. Government budgets get hit because they're not hedged against currency fluctuations. There are also second- and third-round effects which happen in a country which is not as advanced or industrialized. This week Governor Rajan upped the ante by presenting an explosive and controversial paper at the Brookings Institution – literally right in front of former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke – entitled, “Competitive Monetary Easing: Is it yesterday once more?” (Please note that this is the same Ben Bernanke who basically told emerging-market central banks that the US was not responsible for their problems, not all that long ago when he was chairman of the Fed. This was the central banker’s equivalent of saying, “Go pound sand!”) In his paper and oral presentation, Rajan worries openly about the consequences for the rest of the world as advanced-economy interest rates start to normalize. His comments offer us critical insights into the coming climax and resolution of the global debt drama (emphasis mine). Ultra accommodative monetary policy [in advanced economies] created enormously powerful incentive distortions whose consequences are typically understood only after the fact. The consequences of exit, however, are not just to be felt domestically, they could be experienced internationally. Perhaps most vulnerable to the increased risk-taking in this integrated world are countries across the border. When monetary policy in large countries is unconventionally accommodative, capital flows into recipient countries tend to increase local leverage; this is not just due to the direct effect of cross-border banking flows, but also the indirect effect, as the appreciating exchange rate and rising asset prices, especially in real estate, make it seem that borrowers have more equity than they really have… Recipient countries should adjust, of course, but credit and flows mask the magnitude and timing of needed adjustment. For instance, higher collections from property taxes on new houses, sales taxes on new sales, capital gains taxes on financial asset sales, and income taxes on a more prosperous financial sector may all suggest that a country’s fiscal house is in order, even while low risk premia on sovereign debt add to the sense of calm. At the same time, an appreciating nominal exchange rate may also keep down inflation. The difficulty of distinguishing the cyclical from the structural is exacerbated in some emerging markets where policy commitment is weaker, and the willingness to succumb to the siren calls of populist policy greater… Ideally, recipient countries would wish for stable capital inflows, and not flows pushed in by unconventional policy…. But when source countries move to exit unconventional policies, some recipient countries are leveraged, imbalanced, and vulnerable to capital outflows. Given that investment managers anticipate the consequences of the future policy path, even a measured pace of exit may cause severe market turbulence and collateral damage. Indeed the more transparent and well-communicated the exit is, the more certain the foreign investment managers may be of changed conditions, and the more rapid their exit from risky positions. So, Rajan is clearly lining out a framework for understanding the QE-induced bubble boom and the balance of payments crises that could follow in overexposed countries. Unconventional monetary policy pushes far more capital into emerging markets than would naturally flow there in a normalized rate environment, and the easy money tends to lull elected officials into inaction. Following the classic balance-of-payments boom/bust cycle, capital overflows appear to boost growth for a while as leverage grows and policymakers have an increasingly difficult time distinguishing between cyclical and structural forces in the economic data – making it virtually impossible to intervene at the appropriate time. The bubble builds up until the “source country” decides to exit its unconventional policies, wrecking asset prices globally and damaging overexposed “recipient countries.” The problem for emerging markets is that there are no conventional tools for blocking this kind of knock-out punch… except for much-reviled exchange rate interventions and capital controls. Considering the available options, it is very clear that Rajan intends to do whatever it takes to defend the Indian rupee; but he would obviously like to avoid trade sanctions in the process. That’s why he argues so forcefully that emerging markets find themselves pushed up against a new kind of constraint equivalent to the zero bound. Emerging economies have to work to reduce vulnerabilities in their economies, to get to the point where, like Australia, they can allow exchange rate flexibility to do much of the adjustment for them to capital inflows. But the needed institutions take time to develop. In the meantime, the difficulty for emerging markets in absorbing large amounts of capital quickly and in a stable way should be seen as a constraint, much like the zero lower bound, rather than something that can be altered quickly. Expanding on that argument, Governor Rajan argues that there are essentially two kind of unconventional policy: “policies that hold rates at near zero for long” and “balance sheet policies such as quantitative easing or exchange intervention, that involve altering central bank balance sheets in order to affect certain market prices.” In other words, Rajan is arguing that quantitative easing, which aims to lower real rates at the zero bound, is essentially identical to exchange-rate intervention, which aims to explicitly target an exchange rate to maintain or regain competiveness. And that “our attitudes towards [either approach] should be conditioned by the size of their spillover effects rather than by any innate legitimacy of either form of intervention.” For better or worse, Governor Rajan is clearly broadcasting his intent to employ explicit exchange-rate intervention (probably some form of currency peg) or outright capital controls to protect the Indian rupee. I think a lot of emerging-market central banks will follow suit, and harder currency pegs will follow. Otherwise, as Rajan says, The lesson some emerging markets will take away from the recent episode of turmoil is (1) don’t expand domestic demand and run large deficits, (2) maintain a competitive exchange rate, and (3) build up large reserves, because when trouble comes, you are on your own. Notice in the chart below that the currency exchange-rate regimes for countries change all the time. I would expect that volatility to increase in the next few years as emerging markets respond to what is in effect a developed-market currency war, currently led by Japan, though I expect it to heat up everywhere within a few years.

One of the significant differences I’ve noticed this time in South Africa is just how remarkably cheap (for the traveler) everything seems to be that has no, or very little, international component in its makeup – things like food and wine. The rand has depreciated significantly since I was last here; and while that is good for tourists, it is hard on the locals. I had more than a few South African financial industry participants tell me they wished they could come to our conference in San Diego but that the rand had fallen too much to make it affordable. I joked about how I feel the same about travel in Europe, but that was hollow consolation. I spoke some eight times in four days here, plus media interviews, and at each of the venues there was a considerable question-and-answer period. The most difficult questions centered around how South Africa should respond to the actions of the developed-world central banks and especially the US Federal Reserve and what South Africa should do to improve its own current situation? These difficulties are compounded by the fact that a general election will be held here in less than a month. The ruling party, the African National Congress, is beset by serious charges of corruption and an economy that is clearly not hitting on all cylinders, yet it appears the ANC will still get at least 60% of the vote. South Africans are quite passionate about their country and their desire to see it do better. They genuinely wanted to hear some answers from me, but that didn’t make coming up with them any easier. The problem is that there is not much South Africa can do about the policies of central banks other than their own. As I described above, it truly is every central bank for itself. But the South African central bank has local problems that compound its problems. Unemployment is roughly where it was 4-5 years ago, at 24%. Inflation is high and seemingly rising, and the rand is weakening (see chart below).

The South African inflation rate has been relatively stable the last few years at around 6%, after rising to almost 11% in late 2008 and dropping to well below 4% in late 2010.

Treasury bill yields are somewhat lower than the current inflation rate, just as they are in much of the world. But clearly the central bank felt it needed to raise rates in a world where the rand was suffering.

From my friends at moneyweb.com, based here in South Africa: Record low interest rates in the U.S., Europe, and Japan, along with the U.S. Federal Reserve’s multi-trillion dollar quantitative easing programs, caused $4 trillion of speculative “hot money” to flow into emerging market investments over the last several years. A global carry trade arose in which investors borrowed cheaply from the U.S. and Japan, invested the funds in high-yielding emerging market assets, and earned the interest rate differential or spread. Soaring demand for emerging market investments led to a bond bubble and ultra-low borrowing costs, which resulted in government-driven infrastructure booms, dangerously rapid credit growth, and property bubbles in countless developing nations across the globe. The emerging markets bond bubble helped to push South Africa’s 10-year government bond yield down to a record low of 5.77 percent after the global financial crisis:

South Africa’s external debt now totals $136.6 billion or 38.2 percent of the country’s GDP – the highest level since the mid-1980s – due in large part to the emerging markets bond bubble that boosted foreign demand for the country’s bonds. South Africa’s external debt-to-GDP ratio was 25.1 percent just five years ago. $60.6 billion of South Africa’s external debt is denominated in foreign currencies, which exposes borrowers to the risk of rising debt burdens if the South African rand currency depreciates significantly, such as the currency’s 15 percent decline against the U.S. dollar in the past year. To make matters worse, over 150 percent worth of South Africa’s foreign exchange reserves are required to roll over its external debt that matures in 2014. Unsecured loans, or consumer and small business loans that are not backed by assets, are the fastest growing segment of South Africa’s credit market and are essentially the country’s own version of subprime loans. Unsecured loans have grown at a 30 percent annual compounded rate since their introduction in 2007, when the National Credit Act was signed into law. Unsecured lending has become popular with banks because they are able to charge up to 31 annual interest rates, making these riskier loans far more profitable than mortgage and car loans in the low interest rate environment of the past half-decade. The unsecured credit bubble is estimated to have boosted South Africa’s GDP by 219 billion rand or U.S. $20.45 billion from 2009 to mid-2013. Like U.S. subprime lenders from 2002 to 2006, South Africa’s unsecured lenders target working class borrowers who have limited financial literacy, which has contributed to the country’s growing household and personal debt problem. A 2012/2013 report from the National Credit Regulator showed that South Africa’s 20 million citizens carried an alarming 1.44 trillion rand or U.S. $140 billion worth of personal debt – equivalent to 36.4 percent of the GDP. In addition, household debt now accounts for three-quarters of South Africans’ disposable incomes. What’s a central bank to do when faced with such a situation? There is very little else it can do other than try to mitigate the damage if there are significant currency outflows. The rest – the heavy lifting – will have to be done by the government. Which is somewhat problematical, given that the government under current president Zuma has essentially done very little for the last five years. Seven years ago I wrote a very optimistic piece about South Africa called Out Of Africa. Many of the reasons for that optimism remain, including the basic spirit and willingness of South Africans to work and the significant financial-community expertise that is available. But the similarities between then and now end there. Now the South African equity markets are rather fully valued. And the government, which I had hoped would cut through the red tape hindering business, has in fact added to it. Admittedly, there have been some positive changes, and an encouraging document outlining a decade-long economic plan has been developed, but there has been no implementation whatsoever. The policy recommendations I outlined to Zuma in our meetings a number of years ago remain the same. The country must be structured for higher exports and the production that makes them possible. This will require significant labor reform or at least the introduction of commercial business loans with labor-law terms that will allow foreign direct investment to feel comfortable in coming to South Africa. South Africa must realize that it’s competing with every other country in the world when it seeks foreign direct investment. And with regard to manufacturing for the African continent, while the scope of the competition might narrow to other countries in Africa, the competitive principle remains the same. One of the remarkable things I notice as I travel around the world is the business acumen of the South African diaspora. South African expatriates always seem to be running businesses and conducting entrepreneurial activities. Their skills are highly sought after. Those same entrepreneurial skills and desires are found in abundance in South Africa, and that, not gold or platinum or diamonds, is the greatest resource of this country. A restructuring of the rules surrounding the formation of businesses would unleash a South African renaissance in less time than you might think, given the predatory activities of major central bankers fighting currency wars. Free-trade zones, a completely revamped education system that is freely available and teaches skills based upon needs of the future rather than upon academic training suited to the past, and a thorough cleansing of the climate of corruption in the country would also help. This last real problem requires the creation of institutions free from the manipulation of the ruling government that can tackle the problems of corruption. The rule of law must be upheld. Political corruption and crony capitalism must both be done away with, root and branch. (And that goes double for the United States!) On a personal note, South Africa remains one of my very favorite countries to visit. I find the people friendly and engaging; the scenery varies from exotic to breathtakingly beautiful (Cape Town gets my vote for most beautiful city in the world); and the culture is most pleasant. I have high hopes for the country and hope to be invited back often. Perhaps after this upcoming election the leadership will find the courage to take on the entrenched powers and move the country forward. Amsterdam, Brussels, Geneva, and San Diego I will be flying back to Dallas via London in a few hours. It is a long trip, and I must admit that after 25 days on the road I will be glad to be home. I will try to limit travel for a little over two weeks before heading to Europe on another speaking tour. I will be in Amsterdam, then Brussels, and on to Geneva. Then I am back home for a few days before hopping over to San Diego for my Strategic Investment Conference, where you really should join me! And at some point in the next few weeks, I have to begin making plans to return to Italy for the first few weeks of June. I think that rather than making my normal personal comments, I will just go ahead and hit the send button, as I need to shower and check out of the hotel and make my way to the airport. In addition to trying to work through my once-again massive backlog of emails, I think I will take the opportunity on this flight to round up a little science fiction on my iPad. After the last few weeks I need a little break. Have a great week. I look forward to your comments and thank you for taking the time to make me part of your life. Your ready to relax and enjoy the plane ride analyst, |

Shifting bottlenecks in US energy markets

| With the startup of TransCanada's Cushing Marketlink pipeline and increased rail shipping of crude directly to the US Gulf Coast (bypassing Cushing, Oklahoma), a new dynamic in the US energy markets is taking shape. The glut of crude at Cushing (see post form 2012) that used to put downward pressure on WTI is over. With the transport backlog to the Gulf Coast diminishing, crude supplies at Cushing (the delivery point for WTI futures) fell significantly, once again contributing to tighter Brent-WTI spread. Lower supplies at Cushing raised WTI prices while Libya resuming crude exports lowered Brent prices. Brent-WTI spread (source: Ycharts) This development however created another bottleneck. The oversupply of crude has shifted from Oklahoma to the US Gulf Coast. Source: EIA Bloomberg: - Houston and the rest of the U.S. Gulf Coast have more crude oil than the region can handle. Stockpiles in the region centered on Houston and stretching to New Mexico in the west and Alabama in the east rose to 202 million barrels in the week ended April 4, the most on record, Energy Information Administration data released yesterday show.One of the key issues is the US crude oil export restriction. Back in the 70s, the US Congress made it illegal to export domestically produced crude oil without a permit. And permits are tough to get these days, given how unpopular the notion of US oil exports seems to be. The Jones Act which restricts shipping among US ports is also adding to the bottleneck. Bloomberg: - Storage tanks are filling as new pipelines carry light, sweet oil found in shale formations to the coast and U.S. law keeps companies from moving it out. Most crude exports are banned and the 13 ships that can legally move oil between U.S. ports are booked solid. The federal Jones Act restricts domestic seaborne trade to vessels owned, flagged and built in the U.S. and crewed by citizens.Now it's the refineries who will need to clear this inventory and ultimately export the excess product. And that's exactly what is taking place currently, as idle US refining capacity hits a multi-year low. Source: EIA |

The Week Ahead: Another Scare Like 2010, 2011, and 2012?

by Tom Aspray

| It was another rough week for the markets as the heavy selling came as the average investor was trying to digest the significance of the market rigging headline that I discussed last time. The selling hit panic levels on Thursday, but it is too early yet to conclude that the decline is already close to being over. The technical picture last Wednesday allowed for two scenarios and, as of Friday, there is not enough evidence to be confident whether the large-cap Spyder Trust (SPY) and SPDR Dow Industrials (DIA) are going to join the Powershares QQQ Trust (QQQ) on the downside. The plunge in the technology and biotechnology stocks is being tied to the perception that the economy is not strong enough to support the current high stock prices. This view is not really supported by the current numbers, as past market declines in this bull market have come in conjunction with much softer numbers than we are seeing now. The current environment does remind me of the panic sell-offs that occurred in 2010, 2011, and 2012. I have circled these periods on the weekly close only chart of the S&P. For example, on August 27, 2010, there was this Bloomberg headline “El-Erian Says `Alarming’ Data Show U.S. Economy Slowing.” The S&P 500 had actually made its low in early July 2010, but had a secondary low at 1039, the day this article was published. Below the chart of the S&P 5000 is a chart of the S&P 500 Advance/Decline line which reveals that it had made a new high the prior April (point 1) . By February of 2011, the S&P 500 had risen to 1344. In the summer of 2011, there was the massive decline that began in late July that was followed by heavy selling in early August in reaction to the budget impasse and downgrade of US debt. By September, the fear of a double dip recession was being widely discussed. On September 7, a CNBC headline read “US Economy Is Basically ‘Still In Recession’: Fed’s Evans.” The S&P 500 dropped to a low of 1074 on October 4, before reversing to the upside. The A/D line had made a new high in early July (point 2). A week after the low, there was strong technical evidence that the lows were in place, leading to my article “Be Bold, Be Fearless.Buy the Dip.” By April 2012, the S&P 500 was trading well above 1400. The A/D line made a new high that April, but by the end of the month, it had moved into the corrective mode. By May, the concern was over the troubles in the Eurozone with this headline on May 27 from the telegraph “Lloyd’s of London preparing for euro collapse.” The S&P 500, which had traded as high as 1422 at the start of April, dropped to a low of 1266 on June 4, just five days after the article was published. The Euro dropped to a low of 1.2042 the next month and has been moving higher ever since. At the June lows, there were also strong technical signs that the correction was over, as I noted on June 6. In the middle of September 2012, the A/D line made another new high (point 4), which is hard to tell from the chart. By the end of October, concerns over the economy and the outcome of the presidential election resulted in significant selling. The S&P 500 had reached a high of 1474 in September and, by the time this headline appeared on November 7, it was down to 1394. The S&P bottomed on November 16 at 1343 and then rallied to close the year at 1426, despite a year end decline in reaction to the “fiscal cliff.” As the S&P 500 chart indicates, the A/D line has made a series of higher highs in 2013 and early 2014 (line 5) as its most recent high was on April 4. It does not yet show a new downtrend, which would be consistent with a deeper correction in the S&P 500 and NYSE Composite. The bond market does seem to be a bit more worried as the yield on the 10 – Year T-Note looks ready to close at 2.63% as it has dropped below the lows of the past six weeks. The next strong support is in the 2.44-2.50% area and the weekly starc- band. The MACD shows no sign yet of bottoming as it is still in a downtrend, line c. The economic calendar was quite light last week, though the mid-month reading from the University of Michigan on consumer sentiment beat estimates on Friday as it came in at 82.6. This is the highest reading since last July. It is consistent with my view that the consumer will return with a vengeance as the weather warms up. This week we get Retail Sales and the same store sales data was better than expected last week. Also, on Monday, we get Business Inventories. The Consumer Price Index is out on Tuesday, along with the Empire Manufacturing Survey and the Housing Market Index (HMI). Long time readers will recall that it was the HMI that helped confirm the low in the housing market. In 2012, the HMI completed its bottom formation, line c, when it started a new uptrend at point b. On a technical basis, the HMI reached resistance at line a, but shows no signs yet that the uptrend is over. Housing Starts will be released on Wednesday, and also Industrial Production. Thursday we get the weekly jobless claims and the Philadelphia Fed Survey. The markets are closed on Friday for Good Friday but the Leading Indicators will be released. What to Watch The extent of the decline has many wondering if, or when, the NYSE Composite, Spyder Trust (SPY) and SPDR Dow Industrials (DIA) will follow. The NYSE is the broadest measure, and therefore, the most important. The five-day MA of the percentage of Nasdaq 100 stocks above their 50-day MAs has dropped down to 37.96%, which is the lowest level since November of 2012. The three year chart shows that it did hit 15% in June of 2012 and was below 10% in the fall of 2011. For the S&P 500, the 5-day MA is at 62%, which is the mean. In early February, it had a low just above 30%, so this does have further room to fall. According to AAII, the individual investors have become more bearish, dropping to 28.4%, down from 35.4% the prior week. It hit a high of 55% at the end of 2013. The number of bears has also increased to 34%. The NYSE Composite looks ready to close the week just above the quarterly pivot at 10,270. If this level is decisively broken, there is next good support in the 9,900-10,000 area. In early February, the low was 9,732. The McClellan oscillator closed below support, at line c, on Thursday, suggesting that it will move to truly oversold levels below -300 that were last seen in August of 2013. It looks as though the break of the downtrend, line b, at the end of March, was a fake out. The daily NYSE Advance/Decline is getting closer to its trend line support at line d. A close below the low made on March 27 would be more negative. The market internals were about 2-1 negative on Friday. It is important to remember that both the weekly and daily NYSE A/D lines have made a new high recently. Therefore, though the market is acting vulnerable right now, the bull market is not over. S&P 500 The daily starc- band is at $180.58 with the weekly at $177.56. The 38.2% Fibonacci retracement support from the June 2013 low is at $176.67, which is just below the quarterly projected pivot support at $176.97. The daily OBV continues to show a pattern of lower highs and is getting close to stronger support at line c. The weekly OBV (not shown) is still above its WMA, but not by much, and could drop below it this week with another lower weekly close. There is first resistance now at $183.60 with further in the $184.40-$185 area. The daily S&P 500 A/D line now dropped below the most recent low and is testing the more important support at line d. A close below the late March low will confirm a new downtrend. Therefore, any rally will need to be watched closely. Dow Industrials The rising 20-day EMA at $163.40 should provide first support with further in the $162 area. There is more important support in the $160.52 area with the quarterly pivot at $160.88, as well as the support at $160.52. There is next chart support now at $156.95 with the quarterly projected pivot support at $156.25. In February, DIA had a low of $152.44. The daily on-balance volume (OBV) is still acting weak as it has made lower highs, line g, and looks ready to test the February lows. The daily Dow Industrials A/D line, after confirming the upside breakout, has reversed sharply and is back below its WMA. There is next important support at the mid-March lows and the early January high, line h. As I noted in Friday’s column, the comparative analysis of the DIA versus the QQQ suggests it is becoming a leader after lagging for some time. I had noted previously that it was also starting to outperform the SPY. Nasdaq-100 The relative performance has been negative for several weeks as it broke support, line b, and its WMA. The RS line is now back to the late 2013 lows. The weekly OBV will close the week below its uptrend, line c, and its still rising WMA. The daily OBV (not shown) is acting weaker than prices as it has dropped below the early October lows. The Nasdaq 100 A/D has dropped below the lows of the past two months but is actually acting stronger than prices. Its WMA is now declining. There is initial resistance now at $85-$86 with the 20-day EMA at $87.45. Russell 2000 The weekly relative performance will break its long-term uptrend, line f, this week. The upside breakout in March was a false one. The daily RS line still looks very weak as it is well below its WMA. The weekly OBV looks ready to close just below its WMA, so the multiple time frame OBV analysis is still negative. The OBV has further support at the uptrend, line g. The Russell 2000 A/D Line (not shown) is now in a clear downtrend. There is minor resistance now for IWM at $112.50-$113 with stronger at last week’s high of $115.25. |

Twitter shares four years from today — down 45%?

By Mark Hulbert

| A gauge that tracks sales growth suggests there’s more pain ahead

Twitter and Facebook have taken a beating, with their shares down 45% and 19% from recent highs. They could be in for more punishment. That, at least, is the conclusion of a common valuation formula that uses projected sales growth to estimate where newly public stocks will be trading five years after their initial public offerings. Focusing on sales is important because both Twitter /quotes/zigman/23556538/delayed/quotes/nls/twtr TWTR -3.12% and Facebook /quotes/zigman/9962609/delayed/quotes/nls/fb FB -1.06% — like most young firms — are sacrificing earnings to invest in future growth. As a result, earnings-based valuation measures may paint a distorted picture. The sales-based formula discussed here is based on two key assumptions: how fast a company’s revenue will grow over its first five years as a public company, and what its price/sales ratio will be. (The price/sales ratio is calculated by dividing stock price by sales per share.) We know how fast sales have grown at newly public companies in the past because of research conducted by Jay Ritter, a finance professor at the University of Florida who studies IPOs, and two colleagues at the University of California, Davis — Martin Kenney and Donald Patton, a professor and research associate, respectively. They studied 1,700 U.S. companies whose stocks began trading between 1996 and 2007. They found that these companies’ sales on average grew 212%, in inflation-adjusted terms, over their first five years. That is far faster than the growth experienced recently by companies overall. For the S&P 500, inflation-adjusted sales have actually fallen over the past five years. What about the typical young company’s price/sales ratio? According to FactSet, the median ratio for stocks in the Dow Jones U.S. Internet Index on their fifth birthdays was 5.87. The current price/sales ratio for the S&P 500 is 1.64. Using Ritter’s data, forecasting Twitter’s stock in November 2018 — five years after its IPO — becomes a matter of simple math: Multiply its sales per share in the 12 months before going public by 212%, and multiply that by the price/sales ratio of 5.87. Those calculations suggest its stock will be 45% lower than where the messaging service trades today. That is above and beyond the loss the stock has already suffered. A Twitter spokesman declined to comment. The picture at Facebook potential is even less pretty: The social network’s price in May 2017 — five years after its IPO — will be 50% lower than where it is today. A Facebook spokeswoman declined to comment. How can Twitter and Facebook escape these awful fates? Either their sales will have to rise faster than average, or their price/sales ratio will have to be higher. Either is certainly possible, of course. “For companies that operate in ‘winner take all’ markets, the profit potential is enormous,” Ritter says. “This is why Facebook was willing to pay $19 billion for WhatsApp,” referring to the smartphone-messaging app that Facebook acquired in February. Ritter hastens to add, however, that the Achilles’ heel of these winner-take-all markets “is that a company’s niche can evaporate almost overnight.” Investors willing to tolerate that risk may want to instead bet on high-tech companies with more reasonable valuations. Only three such stocks in the Dow Jones U.S. Internet Index are recommended currently by even two of the 42 advisers on the Hulbert Financial Digest’s monitored list who have beaten the Wilshire 5000 index over the past 15 years. (That is a long enough period to largely eliminate the role luck may otherwise play in a good track record.) They are Google, operator of the world’s largest search engine; Yandex, its Russian counterpart; and Qihoo 360 Technology, the Chinese Internet company. When focusing on trailing 12-month sales, all three stocks trade at lower price/sales ratios than either Twitter’s (36.8, according to FactSet) or Facebook’s (19.7). Google’s is the lowest, at 3.1, Yandex’s is 7.6, and Qihoo’s is 11. While these valuations may make these stocks less vulnerable than either Facebook or Twitter to a slowdown in sales growth, bear in mind that the Internet sector still is a lot more volatile than the overall stock market. The Dow Jones Internet Index has historically declined 23% further than the S&P 500 during broad market declines. |