By Paul Brodsky

“All the signs are right this time

You don’t have to try so very hard

If you live in this world

You’re feeling the change of the guard” 1

- Steely Dan

Since we hung up our bond trading shoes in 2006 we have invested with a deeply contrarian macroeconomic view: irreconcilable debt would force the current global monetary system, formally in place since 1973, to fail.

Those that followed our logic and investment rationale have inevitably asked one question: “when?” We have shied away from answering because monetary systems are inherently political arrangements staunchly defended by powerful institutions. Official responses to deteriorating fundamentals can be enormously powerful, especially when ever more monetary easing, fiscal gimmicks and political suasion are foisted upon a marketplace conditioned to accept the established medium in exchange for goods, service and assets.

While we would be foolish to invest under the assumption that we know exactly when the long-term becomes the short term, (or even when it becomes the now), we are confident the global economy is much further down the timeline than just a year ago to rampant hyperinflation and/or a formally-structured monetary devaluation. The Greek bailout and the US debt ceiling impasse are merely different publicly visible manifestations of the same problem: there can be no political solution for extinguishing debt other than formal currency devaluation via asset monetization that would collateralize systemic debt.

The collision between the fraying establishment supported by “reasonable” centrist policy makers and the ulterior natural incentives of the global marketplace is upon us. Public and private sector debt is irreconcilable across all major established economies without more money manufactured to repay it, a process that diminishes the value of currencies and savings. Current events confirm that anticipating a-cyclical economic change is the prudent course for investors regardless of one’s preferred investment horizon.

This paper seeks to provide a roadmap for investing within an environment of paradigm monetary changes and suggests why investment and monetary assets are not currently providing fair warning of this shift.

Shift Happens

It has rarely been as clear as it is today that having a good handle on asset valuation requires connecting macro-economic dots, with an emphasis presently on the actions of policy makers and politicians. The Greek bailout and the debt ceiling impasse have made it obvious that governments have the authority to greatly enhance or diminish near-term asset values. It would seem then that a compelling pursuit for investors would be to try to handicap how policy makers will behave in response to such crises; compelling but pointless, in our view.

We would like to propose a different tact. While it is natural and understandable to take comfort in authoritative controls meant to protect us against adversity, we think that presently the power policy makers have over economies – if expressed through conventional means – is quite limited. The power of human incentives is beginning to overwhelm political authority and the results are not so subtle. The difference between authority and power is beginning to assert itself in the marketplace.

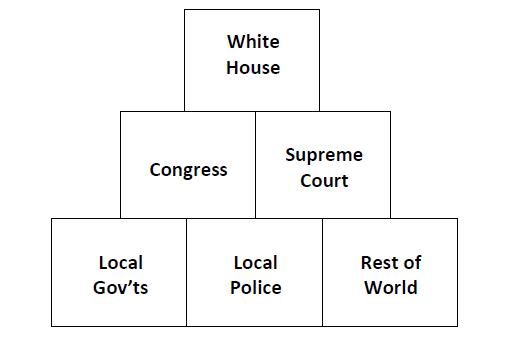

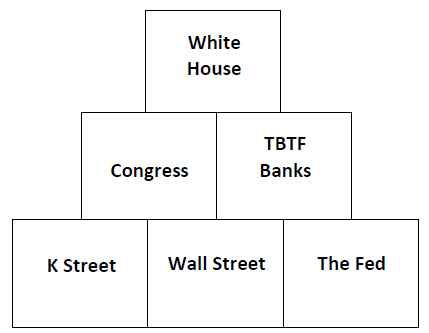

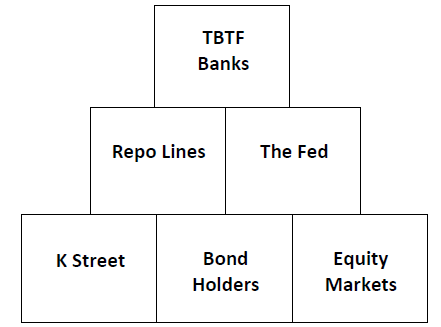

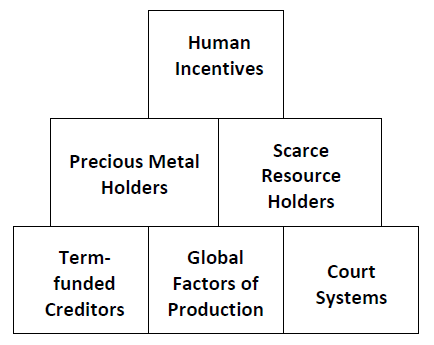

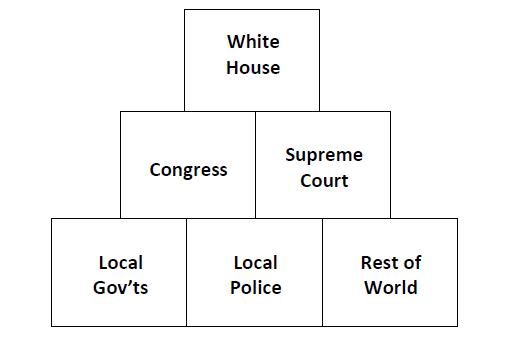

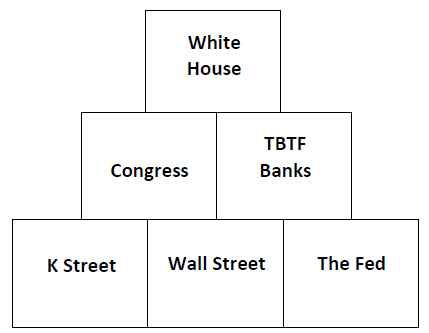

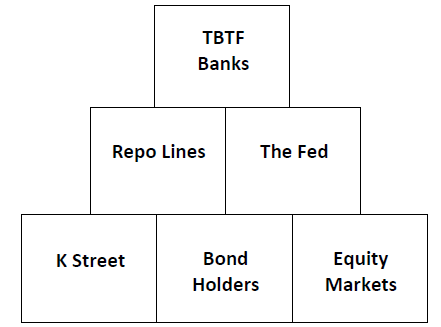

Authority shifts, inevitably and sometimes suddenly, not necessarily from innovation and evolution but sometimes as a direct result of the previous abuse of power leant to authoritative bodies. Some will naturally recognize shifting authority before others and, as history shows, oftentimes before institutionalized authorities themselves. Below, we diagram perceptions of power in the United States as we imagine those from various points of view may perceive them. We argue they are not power structures at all. They are perceived authoritative understandings.

Perception of Power: US School Children

Perception of Power: Washington

Perception of Power: Washington

Perception of Power: Wall Street

Perception of Power: Keynesian Economists

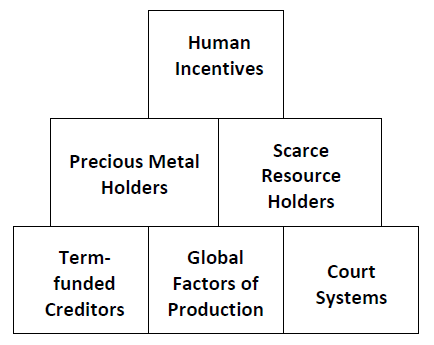

We have no insight beyond what we learned in civics class into which people or bodies may start wars, get legislation enacted, or change the fate of millions. Our point is that authority is dynamic but ultimate power is not. This further implies that current asset values backed by current authority may have asymmetrically negative risk characteristics, in direct contrast to sustainable value backed by sustainable power. Below, we conjure an ultimate power structure that we feel describes the rank of forces should contemporary systems break down. It reflects our view of the forces that would drive the formation and priority of value following structural economic changes:

Perception of Ultimate Power: QBAMCO

No doubt you will disagree with any or all of these diagrams and may choose to compose one yourself. The point of this exercise is that authority is designed to be forever but history repeatedly shows it is not.

We think that in the current environment it is most prudent to invest alongside power. In the end, pure economic principles trump fluctuating political imperatives, the pursuit of relative nominal returns, or even standing armies. When the going gets tough, power takes control. Wealth backed by current authority is dynamic while wealth backed by real power is sustainable.

The following sections provide specific identities that substantiate this view. We think these relationships explain clearly the critical issues behind the events occurring today in Brussels and Washington and, once internalized, allow one to see the inevitability of structural monetary system change and to develop a comprehensive strategy for maintaining and enhancing wealth.

Political Construct #1: Money & It’s Poseurs

We cannot seem to escape reading or listening to confused monetary and economic identities leading to errant investment conclusions. Below, we discuss proper monetary identities and their practical implications:

In the current global monetary system there is only one form of money that matters in the end – base money (M0, or currency in circulation plus bank reserves held at the Fed). Broader measures of “money” (i.e. M1, M2 and M32) are merely claims on the stock of base money — claims that cannot be satisfied because they cannot be withdrawn from the banking system unless more base money is created. When we combine all US dollar “monetary aggregates” (commonly yet incorrectly referred to as “the money stock”), base money (M0) is presently 18.7% while M1, M2, M3 is 81.3% of the total. Thus, 81% of dollar-denominated savings (bank deposits, CDs, money market funds, etc.) is literally and functionally systemic debt, which further implies that the US dollar is, as Walter E. Spahr wrote in 1976, an “irredeemable currency”.3

On top of this uncollateralized debt money sits more credit denominated in it. Base money is multiplied by the commercial banking system and distributed throughout the system. These electronic credits are used commercially (as money) by economic participants for working capital, consumption and wages, and are also used (as money) by economic participants to purchase property, such as resources, businesses, real estate, corporate shares, and bonds. Thus, in the current monetary regime, what is generally perceived as “money” is in reality claims on money and the real value of property is subject to the ratio of systemic claims on base money to base money.

Theoretically, base money and its credit derivatives should be thought of as follows:

1. Base Money – M0, in terms of dollars or gold (an entirely independent debate): Only base money can extinguish debts denominated in it, including the electronic credits comprising all other aggregates.

2. Reserved Credit – base money that is leant: Say Bob lends Tim $100. Aggregate systemic credit would increase by $100, as would aggregate indebtedness. The net result would be zero. There would be no more or less “money” in circulation. Credit today is not reserved in the US or anywhere else.

3. Unreserved (Bank) Credit – leveraged claims on base money: Say Bob deposits $100 in ABC Bank. Through the fractional-reserve lending process, that $100 grows to $1,000 on ABC’s balance sheet. While the base money stock is unchanged, there is an illusion of $900 more base money in circulation when in fact claims on that base money were created. In the end, this illusion must be reconciled either by an overt expansion of the base money stock in the amount of $900 or, alternatively, a discount/write-down of existing bank deposits by 90%. This describes the global credit system today.

Practical Impacts: The operations of a contemporary economy and its financial system depend upon the fractionally-reserved “lending” practices of the commercial banking system. Given the extraordinarily high degree of leverage (unreserved credit) in the banking system presently (26:1), deleveraging must occur via an expansion of the base money stock or else the banking system would fail (Exhibit A: political priorities from 2008 through the current period). Ultimately, the banking system demands more base money, which its central bank can create on demand at no true economic cost to itself.

Base money expansion, (i.e. “inflation”), is secular or, as history shows, permanent in nature. A doubling of the base money stock (either by central bank decree or a newly-discovered gold bonanza) would not be systemically disruptive. In such a case one would expect a commensurate doubling of the general price level, all else equal. There would clearly be wealth transfers from savers to debtors in such an event, but the economy would remain perpetually reconciled. Monetary Base expansion would be transparent and quantifiable in real time whereas in the current system unreserved bank credit expansion is not.

We would argue a system built upon unreserved bank credit expansion is inequitable, regressive, opaque, the source of asset boom/bust cycles and the root of virtually all the financial, economic and political chaos we are experiencing today. We assume this is in the process of being more widely intuited by global societies. Those that understand monetary identities are best prepared to shift wealth in advance of the necessary de-leveraging that must take place to restore equilibrium.

Political Construct #2: Public/Private Economic Partnership

The US government traditionally funds itself on the back of its private sector; directly from its citizens through taxation and by using the banking system as an intermediary to borrow. Very recently, however, Treasury has used the banking system to broker a good portion of the government’s debt issuance to the Fed. The Fed sits atop the banking system and has been granted monopoly status by Congress to create base money. Very recently it has begun creating new base money to pay for Treasury’s new debt, (“monetizing debt”). Theoretically, the Fed can create base money to purchase equity owned by the Untied States, such as productive resources, land or gold. This would be “monetizing equity”. Ultimately, we believe this is the way out: the Fed will formally devalue dollars vis-à-vis gold by tendering for private sector gold at substantially higher prices and remarking Treasury’s gold.

Political Construct #3: Debt Ceiling & the Debt Ceiling Drama

The debt ceiling debate was not a fundamentally big deal. The Fed holds more than $1 trillion in US government obligations. If it chose to do so, it could have forgiven the Treasury of its obligations, which would have created substantial room for more Treasury borrowing and would have eliminated the need to raise the debt ceiling. Or, as Jack Balkin, a law professor at Yale, pointed out, Treasury is legally entitled to issue platinum coins in any denomination. He suggested Treasury could have minted a coin, stamped $1 trillion on it and then deposited it at the Fed. Voila. (Maybe Treasury could even mint 10 of them?) Obviously these two ideas would be enormously inflationary, but so is raising the debt ceiling. The point here is that everything about money is politically subjective in a fiat currency system (and all global currencies are now fiat and baseless).

Political Construct #4: Don’t Fight the Fed

The earliest recollection we have of the term “don’t fight the Fed” was from a Marty Zweig appearance on Louis Rukeyser’s “Wall Street Week” in the mid-seventies. His point was that stocks fall when the Fed is tightening credit and rise when the Fed eases. Zweig’s advice is as valid today as it was then, but with one big caveat: once incremental systemic credit ceases to produce incremental real wealth and capital, most stocks do not produce positive real returns regardless of whether the Fed eases and regardless of nominal equity returns (See “False Signals” below).

To be sure, the Fed remains a powerful force, but not in the conventional sense. Why? Because it, too, is a victim of its own generosity and now has a massively leveraged balance sheet. This has greatly diminished its ability to protect the banking system against broader economic adversity using conventional means. According to Benn Steil, Director of International Economics at the Council on Foreign Relations: “the 2011-model Fed sports a 55-1 leverage ratio, and is so exposed to interest rate risk that a roughly 40 basis point rise in long-term yields would wipe out its capital. It too could be in line for a Treasury bailout. Given that the Fed is currently the world’s leading consumer of Treasury debt, this would be the ultimate monetary irony.” 4

With leverage of 55:1, it would seem the markets may exit the Fed before the Fed can exit the markets (but don’t bet on it). With interest rates already nil, two rounds of quantitative easing already in the books, its balance sheet already bloated, and its credibility in Congress fading fast, the Fed must choose now between saving itself and the banking system for which it advocates, (and maybe saving the US Treasury to boot), or saving the currency unit it underwrites. We do not think the Fed will destroy the banking system or itself TBTF bank shareholders). Rather, it will ultimately choose to destroy the currency. Central bankers have proven repeatedly that always and everywhere they have one imperative – to nurture and sustain the growth of unreserved debt. That is the trough from which banks feed. Conveniently for the banks, monetary inflation is also a political imperative — protection against cascading financial instability. Don’t fight the Fed!

Political Construct #5: Output & Animal Spirits

The more money and credit manufactured in an economy, the higher its nominal output. Curiously, most economic and market observers still do not seem to recognize this connection as the most fundamentally reliable leading indicator of nominal asset performance. Instead most observers still equate rising output solely with increasing demand for goods and services. In a fractionally-reserved, baseless monetary system, nominal GDP can increase even if production and demand for goods and services decline. All it takes is higher nominal prices, which are directly linked to the quantity of money and credit – the higher money and credit growth, the more money and credit chase goods and services, the higher prices rise, the higher nominal output growth.

Thus, money and credit growth equal nominal output growth, all things equal, even if unit growth stagnates or declines (e.g. US economy thus far in 2011). But money and credit growth do not equal real growth. The US economy has experienced unreserved credit growth over the last thirty years that finally overwhelmed the system. As we are seeing, this has now actually led to contractionary pressures. The demands to deleverage the economy brought about by overwhelming unreserved credit growth has made production fall and unemployment rise.

So nominal GDP growth is a derivative of money and credit growth, not the other way around, and both are not necessarily signals of an economy’s real production, productivity or even viability. The amount of brain cells devoted over the years to figuring out whether to buy, sell or hold assets by speculating on the future of “animal spirits” may represent the biggest waste of human potential since World War II. Animal spirits do not matter if there is a baseless money system and a willing monetary monopolist…until the system fails.

Political Construct #6: Fear of Rising Debt-to-GDP Ratios

Economists and politicians are currently wringing their hands about rising Debt-to-GDP ratios throughout established economies. Hmm. Debts are claims on currency, not GDP. It is not the Debt-to-GDP ratio that matters, but rather the debt to the base-money stock. As we have discussed, only base money can extinguish debt — widgets cannot. While it is conceivable that people would think GDP growth makes it easier to service outstanding debt, such a notion is theoretically and practically inaccurate.

If you create more unreserved debt to create more nominal growth, systemic leverage is increased! It defeats the purpose of the entire exercise, unless of course the purpose is to delay facing reconciliation. Clearly, policy makers and banks have preferred creating unreserved debt rather than base money, perhaps because unreserved debt targets asset price increases (and concentrates wealth) rather than targets goods and services pricing (which spreads the burden of higher prices across the population)? Where “money” in a system is mostly unreserved credit (not base money) and output is exchanged for this “money”, output must be encumbered. Where output is encumbered, it is not real. So trying to figure out whether output will grow enough to service outstanding debt (ostensibly by reducing the Debt-to-GDP ratio) is a wayward pursuit. It cannot.

Let us assume both Mr. Smith and Mr. Jones are indebted. In an economy with a fixed stock of base money, if Mr. Smith were to increase his income due to productive activity, then that would leave less income for Mr. Jones to service his debt. The enhanced creditworthiness of Mr. Smith thus occurs only at the expense of Mr. Jones’ creditworthiness.

Now let us introduce the modern central bank and fiat currency system. The central bank, as the lone supplier of base money to the aggregate economy, is also the lone determinant of the creditworthiness of the aggregate financial system. GDP growth does not produce base money nor does its contraction dissolve it. While incremental contributions to GDP growth by Mr. Smith most certainly improve his particular creditworthiness, Mr. Jones still suffers. Ultimately it remains a zero-sum game. Thus, the creditworthiness of any financial system is entirely a function of the debt-to-base money ratio, not the Debt-to-GDP ratio.

So when Rogoff and Reinhart, brilliant as they truly are, warn us that we should not let debt rise to 90% of GDP or else history shows the game will be over, we should both heed their advice and then ask ourselves: “so what actually creates the debt in that ratio?” The answer for the most part is the extension of unreserved credit. Finally, ask yourself this: if higher GDP makes a nation more creditworthy, then why do weak economic reports cause the Treasury market to rally? Treasuries cannot default with the Fed around (more on this below).

False Signals in Stocks & Bonds

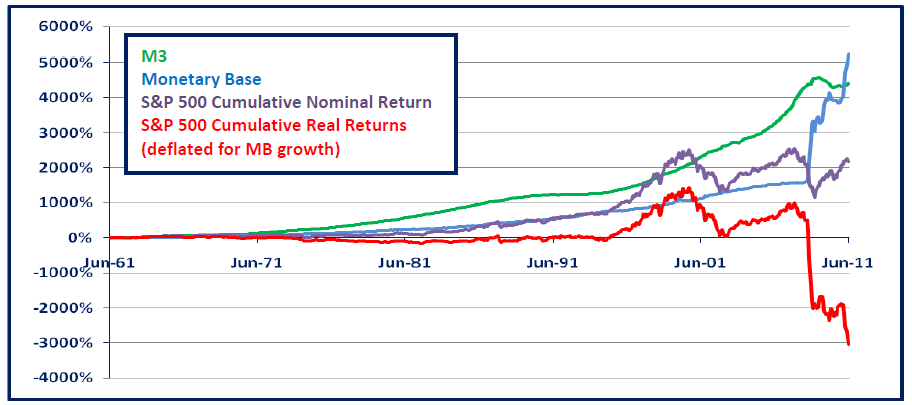

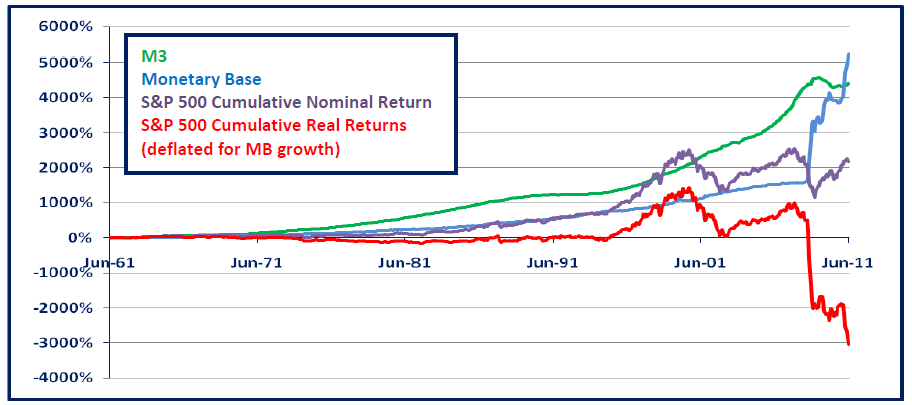

We think the markets are grossly mispriced vis-à-vis the likeliest economic outcome — the necessary contraction of the debt-to-base money ratio (currently 26:1). Below we review stock and bond in the US and show how they are sending false economic signals. The graph below illustrates how investors in the US stock market are having their real wealth destroyed and why most have not realized it yet. It shows the nominal and real cumulative returns of the US stock market since 1960.

As we can see, the nominal return of the S&P 500 (purple line) has fluctuated since the mid-nineties in what seems to be a cyclical pattern. Meanwhile, the currency in which it is denominated (US dollars – blue line) has recently been greatly diluted, making the real returns of the index greatly negative (red line). Again, base money (blue line) is M0 or high powered money – the stuff policy makers presume will be multiplied many times in the banking system to produce more credit (e.g. M3, green line).

While unreserved credit expansion may provide higher nominal GDP growth, more consumption of the underlying goods and services produced by the companies that comprise the S&P 500, and more sponsorship among investors who may buy more shares, it would also produce decreasing purchasing power of each share upon its redemption. This would mean negative real returns. It is a game of mirrors — raise the share price, destroy the currency (through the eventual necessity for base money inflation) or save the currency, trash the share price (as previous unreserved credit expansion deflates).

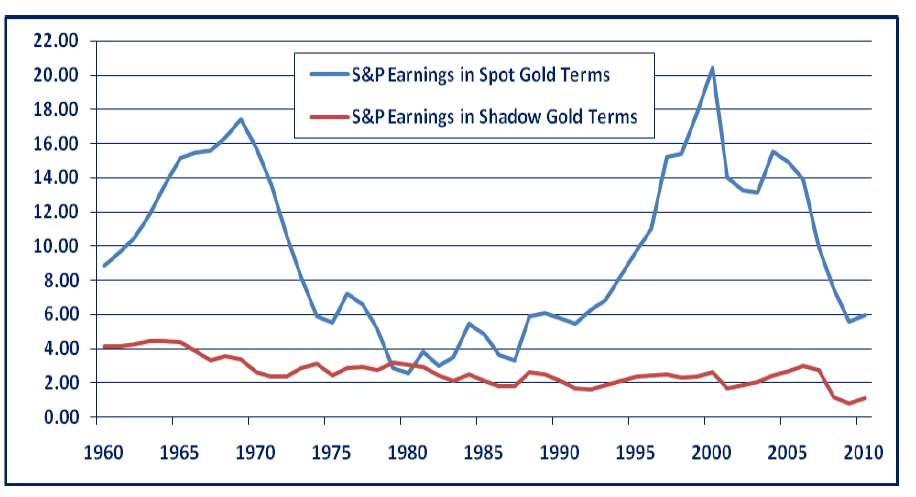

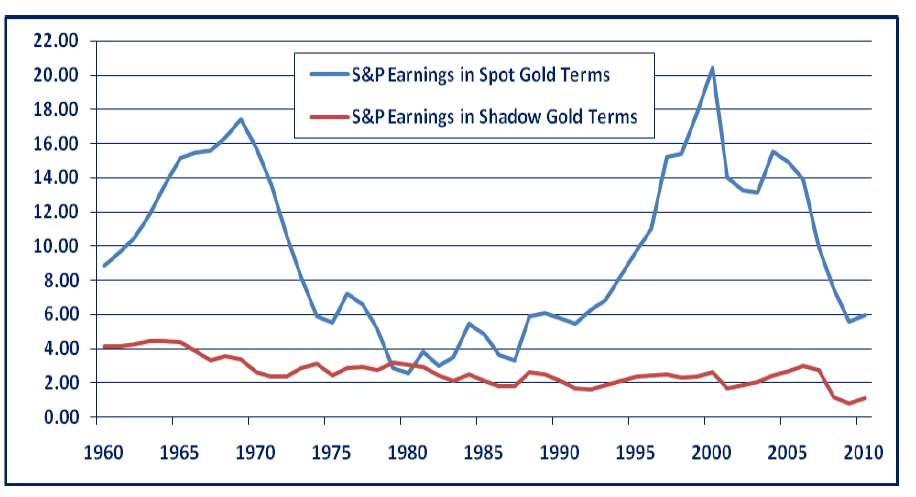

One argument for the stock market recently has been rising corporate profitability. Regrettably this valuation metric provides no solace for the investor seeking positive real returns because earnings are also denominated in diluting US dollars. The graph below shows earnings in what we would regard as real terms. They are adjusted for the spot gold price and for our Shadow Gold Price (SGP).5 The graph shows real earnings are nothing to write home about, and in fact have declined over a long stretch of time.

Is it fair to deflate earnings by gold? After all, you may argue, spot gold and the SGP have grown more than earnings so adjusting earnings for them unfairly punishes earnings. We would argue in response that this is a legitimate methodology for finding real earnings because gold has always been the fallback currency when fiat currencies fail. (See “Neon Gold Swan” below.) And the record of failure for fiat currencies is perfect.

So, despite seemingly healthy nominal earnings, companies that comprise the S&P 500 are collectively producing very little in the way of realistically calculated real earnings. Simply, inflation is a monetary phenomenon and money growth (and unreserved credit growth that necessitates future money growth) has vastly outpaced earnings growth.

What about bonds? Are they providing investors with positive real returns? The answer is that it depends on the investor, their strategy and their time horizon. With US benchmark and tertiary yields across investment grade bond markets ranging from 0% to 7%, and with base money having just grown over 200% from $850 billion to $2.7 trillion in three years, we would argue that the fixed income markets offer deeply negative unlevered yields. However, leveraged investors have been able to generate positive real returns, at least in terms of current income.

The current 10-year Treasury note (3.125% of 5/21) recently traded to yield 2.74% ($103.28). Presuming a reasonable expectation of a 1% real yield, and assuming true price inflation is closer to the SGS Alternative CPI-U Equivalent Year-over-Year Index of 11.13% in June6 , we would argue the current 10-year note should be priced today to yield about 12.13% ($49.20). Are we mad? How can there be such a wide disparity and why on Earth would levered investors think they could generate positive real returns today at sub 3% yields given such a disparity?

Well, unlike most leveraged investors in the equity market, who may borrow two times their equity, the majority of bond investors driving marginal pricing such as primary dealers, hedge funds and central banks are quite a bit more leveraged. We would argue the Note is not trading at 49 because levered investors have incentive to collect 25% or more in current income (2.74% x 10 or 20) while awaiting their annual bonus or performance fee (or, in the case of the Fed, propping up the economy). Neither do leveraged arbitrageurs long Treasuries and short other fixed-income products care about absolute yields or positive real yields. Nor apparently do global investors from parts of the world where concern for the nominal creditworthiness of their sovereign debt is openly in question.

Are these levered market participants taking significant risk by owning duration? Ultimately yes, quite a bit of it, but it seems there may still be time before they have to worry about rising rates. Given its already precarious balance sheet, it would be reasonable to expect the Fed to cap longer duration Treasury yields. This would involve more direct purchases of Treasury paper or the ongoing threat of doing so. We could envision commercial banks using excess reserves to buy Treasuries, doing the Fed’s job for it, and perhaps even strengthening balance sheets in the process by swapping their dubiously-marked bonds (to the Fed) for Treasuries (from Treasury). The Fed would become “the bad bank” for its shareholder banks. Of course this would greatly impair the Fed’s solvency. No problem. The Fed could then buy something guaranteed to appreciate on the other side as it inflates the monetary base (maybe something shiny?) that would then be marked higher.

We could also imagine fiscal policy makers to get in on the act to provide incentives for more public sponsorship of Treasury debt. As Alan Abelson relayed Stephanie Pomboy’s thoughts:

“…one proposal Stephanie envisions is to require 401(k)s to hold a certain percentage of their assets in Treasuries at the risk of losing tax-free status. Another is encouraging public pension funds to fatten up the share of their portfolios given over to Treasuries. Still another is enticing companies to put a chunk of the nearly $1.9 trillion in cash “burning a hole in their pockets” into Uncle Sam’s obligations, possibly as part of a deal for a tax holiday to bring home the huge cache of foreign profits sequestered abroad.”7

As we discussed recently, (“Brace Yourself”), cynical gimmicks conjured by Washington are coming fast and furious (e.g. the random release of surplus crude oil and congress re-calculating the CPI). Why not expect Congress and the White House to recruit the investor class to fund an insolvent government? (Of course, such de facto capital controls would not be a true solution. They would threaten the equity and real estate markets by crowding out investment. If unreserved debt pressures crave x amount of base money, then taking money out of mattresses and putting it back into circulation is functionally equivalent to quantitative easing.)

Economically-speaking, whether money printing, fiscal measures or both create demand for more Treasuries, the net result must be higher goods and service prices that lock-in deeply negative real returns for unlevered bond investors and, eventually, capital losses for leveraged ones. But shorting Treasuries may remain a mug’s game a while longer. The workings of the modern central bank machine virtually guarantee increasing consumer prices, yet benchmark interest rates will not send this signal until it is too late.

In summary, financial asset markets are not being accurately priced for real rates of return and so they are not sending accurate economic signals. Focusing on nominal returns and assuming assets provide accurate economic signals is a cruel joke on most investors, economists, and policy makers. Negative real returns is death by a thousand cuts to the naïve pensioner, fixed annuity holder, retiree, and anyone else seeking to fund future obligations through asset performance.

To the Truly Independent, the Spoils

Are the markets irrational? No, they are perfectly rational but the majority of investors that comprise them are incentivized to invest without regard for accurately calculated positive real returns. So we think while the markets are comprised of rational investors, market pricing is not rational. There are some glimmers of hope, however, that the institutionalized investment mindset is being forced to confront reality.

Jason Zweig, who writes the aptly named “Intelligent Investor” column in the Wall Street Journal, broached a topic on July 23-24 that few have dared. He asked what if there was “an event that is unthinkably rare, immensely important and blindingly obvious?” Zweig was referring to the debt ceiling impasse and the doe-in-the-headlight mentality being broadly demonstrated among professional investors. He noted “many investors seem to be coping with what seems to be an obvious risk simply by closing their eyes.”8 Zweig was on to something. Why would investors rationally do this?

Well, consider that investors across markets and domains are effectively funded with 30-day money. Even if their investment lock-ups or horizons are thought to be longer, portfolio managers still have to report performance monthly to their outside investors or their investment boards. They are under constant pressure to produce short-term returns or face investor scrutiny (or public shame) that threatens their capital base, further capital gathering or even their careers. As a result, the time horizon to be right about long-term asset mispricing is very condensed, forcing rational investors in the business of asset management to migrate towards being reactive performance chasers and closet index huggers rather than independent, anticipatory investors.

Mismatched or potentially mismatched funding has made the business of investment management very different from rational, value-based investing.

Whether or not they know it, term-funded or self-funded investors (of any size) willing to anticipate secular changes that would lead to significant asset re-pricing have a great advantage. Looking across the valley allows the investor to accept a random path to more definable outcomes, (such as the ones we argue), while those beholden to momentum and current trends churn themselves silly (and distort near-term prices that well-funded independent investors may exploit in the process). We think this explains why most investors do not see turns in the market or are not positioned for turns in the economy. Markets do not send proper economic signals repeatedly because investors are stupid; it is because the fiduciary investment process is corrupt.

As the saying goes, all of life may not be 5:2 odds but that’s how you bet. That silly sentiment is driving market pricing. Most investment capital is managed by “prudent” bodies, and as good fiduciaries and business people they must be positioned with the crowd, right up to the point where they are gravely wrong. As a strategic matter, trying to define outcomes based on the incentive structures of all concerned seems the best approach to investing in the current environment. We feel the prudent course presently is to position for substantial change, and no amount of tortured logic or asset mispricing will shake us out of our positions.

Extend, Pretend, Emend & Defend

The EU policy of Extend, Pretend, Emend & Defend (EPED) moves intrepidly on. Under the terms of the Greek bailout, banks are expected to buy back €50 billion of Greek debt over three years (we shall see) and the Greek government is supposed to use the bailout money to buy back debt at a discount (again, we shall see). The pledge of €109 billion that the EU has agreed to channel Greece’s way will ostensibly allow Greece to avoid sovereign default through 2014, that is unless Italy, Spain or some other EU sovereign faces a challenging coupon payment in the interim, which would require an emergency bailout and deplete the €440 billion funding the European Financial Stability Facility.

We felt the need to add “Emend & Defend” (ED) to the well-worn “Extend & Pretend” (EP) strategy for avoiding creditor (and oh yeah, debtor) defaults. Emend & Defend allows policy makers to appear to perform at a critical time but not to be contractually obligated to satisfy the beneficiary (much the same way the other ED is treated J). So we think Greece has not been bailed out through 2014, as EU authorities proclaim — only until the next troubled debt payment arises anywhere in the confederation.

Tick-Tock

Meanwhile, the ridiculous public display of vim, vigor, ignorance and pettiness surrounding the US debt ceiling shows nothing less than the true failure of representative government, one in which the public/private economic partnership supposed to define liberal democracies no longer represents the long-term best interests of its societies. Republicans showed they will not raise taxes and Democrats showed they will not cut spending. Congratulations, you both won and your economy lost (and with it the future hegemony of the US dollar). If any observers and investors retained hope that a political solution would set a new course to US solvency, this circus no doubt dashed such hopes. We must admit our outrage is feigned. This had to happen.

There issue that should be gurgling up to the public consciousness is this: there can be no political solution to US debt and deficits because politics and policy cannot represent both current and future generations (nor debtors and savers) at once. We take the outcome of the debt ceiling debate as confirmation that there will have to be a crisis before a political solution is found, and that the solution ultimately used will be what we have argued: currency devaluation through Treasury/Fed asset monetization (i.e. gold).

We are seeing signs that such a crazy scheme might soon seep into public consciousness. When asked directly if gold was money in his July congressional testimony, Ben Bernanke proclaimed it was not. When asked why the Fed still had it on its balance sheet, he could only mumble “tradition”. Gold has always been money and will become generally perceived as money again, once all other avenues are exhausted. We assume Chairman Bernanke will not be the last to know.

The current problems in the EU and US may be traced back to the exact same source – overwhelming, irreconcilable systemic debt that cannot be extinguished without great monetary inflation or great credit deterioration. We should expect a political solution that would constitute “a tail event”, such as monetizing assets. We’ll borrow from Marty Zweig and agree; “don’t fight the Fed”, and from Jason Zweig and call it “a neon swan”.

The Neon Gold Swan

The principle we believe has begun to assert its will on the West is this: accumulated capital, (not balance sheets filled with debt and levered assets), is ultimately sovereign over all other economic and political constructs. We argue global capital, in whatever form it takes and wherever it is, has begun migrating and congealing around the pursuit of storage rather than the pursuit of production denominated in fiat currencies.

Proof is everywhere. Price increases of precious metals and scarce resources are highest over the last decade in currencies with the greatest money growth. Wealth holders are converting their paper holdings to scarcity. Why?

1. Scarcity and desirability = value

2. Money is freely exchanged for other elements of value

3. Therefore, money = value = scarcity and desirability.

4. Baseless currency can be supplied infinitely and subjectively and therefore is not money

5. Thus, gold = money.

The likely reason most people cannot get their heads around the concept of gold-as-money may be because leveraged paper claims on gold (i.e. gold futures) fluctuate daily on commodities exchanges. Gold may seem to most people to be an investment, in the same speculative way pork bellies or tech stocks are investments. Like the wayward incentives creating mispricing and sending false signals to stock and bond holders presently, tortured logic is also skewing the perception of gold.

Futures on gold or anything else are levered paper bets made mostly by levered financial asset investors. Monthly (sometimes weekly) volume in precious metals futures contracts greatly exceeds their above-ground quantities. Unlike other futures contracts, gold futures do not reflect the reality that gold bullion is a scarce and incorruptible monetary asset that is not consumed.

We believe holding physical gold or shares in companies that own and mine physical gold will enhance one’s wealth by giving him or her more relative purchasing power than others in society who do not own it. (The same may not be said for futures or other derivative gold instruments such as non- or partially-backed ETFs or swap agreements that may not be settled for actual bullion.)

The concept of increasing one’s wealth by stabilizing or improving one’s purchasing power, via currency conversion of baseless money into gold, has been lost on most Americans for three or four generations. In fact, the prudential and appropriate strategy for currency conversion is even lost presently among most Europeans who have a far more sophisticated sense of dynamic currency values. Flocking to Swiss Francs or Canadian Dollars is fine in relative terms but we feel it will prove wholly insufficient for protecting one’s purchasing power. All paper currencies will be devalued to the one scarce currency that expresses itself when the nominal deleveraging process destroys debt money across all domains — gold.

The Practicality of Gold as a Currency

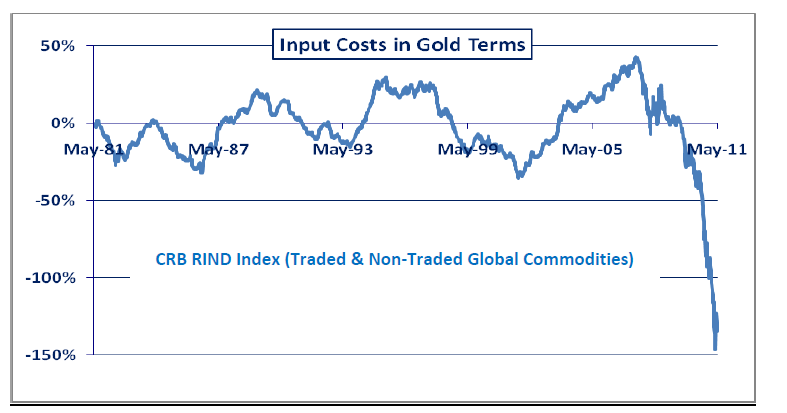

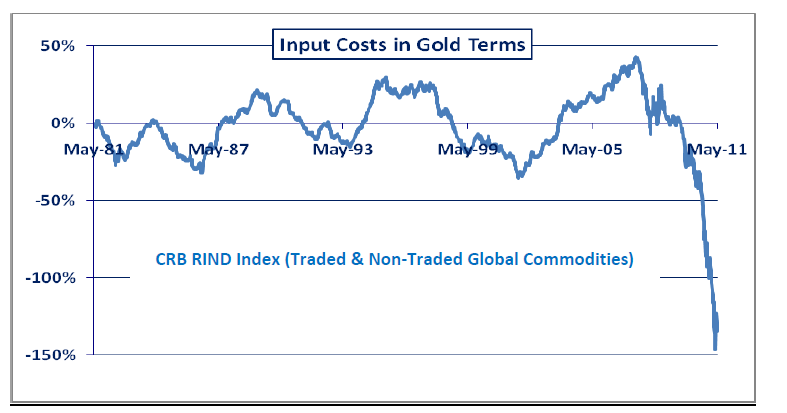

The graph below is a proxy for the ongoing cumulative change of global input costs over 30 years in terms of US dollars. It simply shows the change of an index of traded and non-traded global commodities that we consume daily and that go into finished goods. There is nothing remarkable about it, other than it shows in graphic terms significant price increases associated with USD monetary inflation.

Given our assertion that gold will be the surviving currency, however, it seems to us that the proper way to judge the change in the value of goods and services would be to deflate their nominal prices in gold. The graph below is the ongoing cumulative change of global input costs over the same time period deflated for stabilized wealth (i.e. deflated for gold, which maintains scarcity over paper currencies). So the graph above shows the change in input costs for dollar holders and the graph below shows the change in input costs for gold holders.

These graphs illustrate the commercial importance of picking the right currency. They also imply broader economic and social benefits few consider. In many modern finance-based economies such as the US we have been conditioned to think that input costs for goods are relatively insignificant in the broader scheme of things because our manufacturing bases have become smaller relative to our service sectors; however, as we are discovering presently, the general price level – as well as overall consumption — relies upon global input costs. Very few people know they should care about the graph immediately above because very few people, businesses or governments have owned or have funded their consumption or operations with gold.

The rejoinder to this discussion would be: “Big deal! Everyone knows gold has risen in US dollar terms and so owning it would naturally cheapen everything else for its holders! What if gold drops in the future? The opposite would happen!”

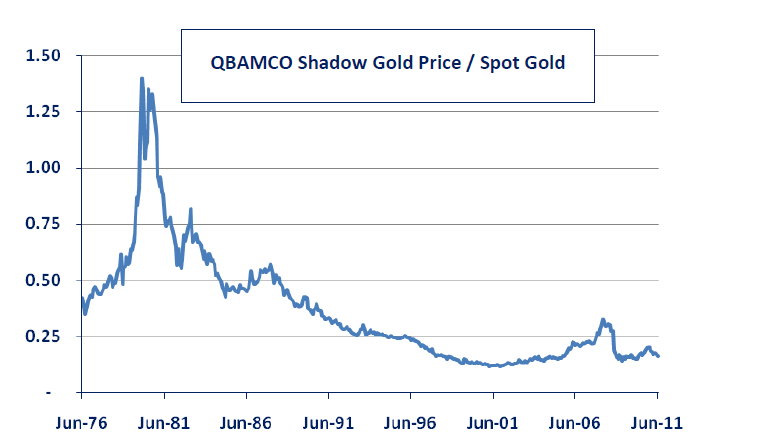

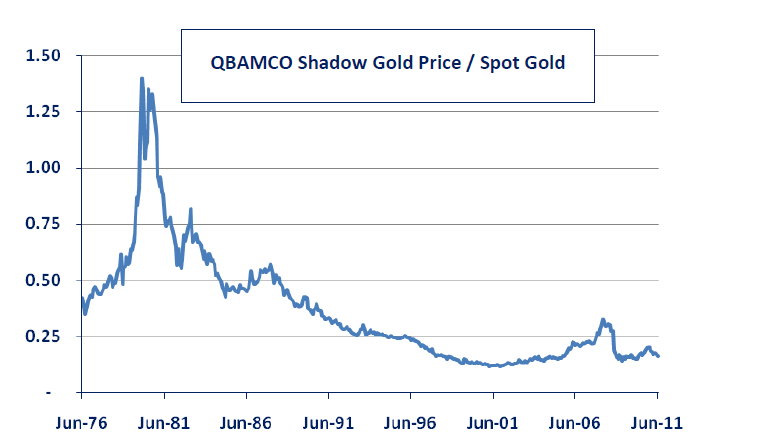

To refute such an assertion we would again note our Shadow Gold Price. Based on precedent and proper identities, (monetary base divided by official gold holdings), the SGP shows that gold is currently very cheap by a multiple of almost five times given the amount of monetary inflation already undertaken in the US by the Fed:

And the graph below is the Shadow Gold price divided by the Spot Gold Price:

Clearly, the intrinsic price of gold in US dollar terms is at its lows vis-à-vis the spot price. Principles, fundamentals and technicals matter, and they all seem to point toward gold becoming more valuable in terms of other currencies. And if central banks continue to manufacture more currency, gold would become that much more valuable.

Change for a Dollar

If the economic manner in which the US is operating is not in the sustainable best interest of its owners — Americans increasingly becoming poorer and unproductive in real terms — then it seems logical there will be forced change. As just proven, the political dimension in the United States and around the world has the legal authority but not the political will to act preemptively to re-balance global economic equilibria by reinstating monetary discipline. Only the power of popular dissention can force authorities to pull the ripcord on the current system.

We do not think there will be a political coup d’état or that Western democracy and capitalism will be threatened. We do believe the “revolution” that must occur, (if it is indeed a “revolution” at all), will be only monetary in nature. The most likely path is that an event will force global monetary and financial market seizure. This seizure would force a recapitalization of nominal asset prices to reflect their real values. People, businesses and nations in possession of durable assets and resources, like primary homes, cars, inventory and scarce resources, will continue to own them while a new system of quantifying their value is worked out.

We think precious metals will increase their purchasing power vis-à-vis all baseless currencies. We also think consumable natural resources with inelastic demand properties will, at a minimum, retain their purchasing power (which is to say enjoy substantial price appreciation in fiat money terms – far more than financial assets relying on existing leverage or future systemic leverage growth).

Tipping Point

So when will financial markets better reflect sustainable economics than a series of dubious political constructs that have placed valuations in a constant state of disequilibrium? Well, how about this: when the milk to Dow Jones Industrial Average ratio widens to the point where only equity holders are oblivious to milk prices?

Imagine an island with ten people on it and each person has $100 and a $200 equity portfolio consisting only of shares in the island’s coconut milk farm. The people on the island consume 20 coconuts-worth of milk a day. The island’s milk output and wealth cannot be increased with the addition of money, only with the addition of consumer demand. Now imagine that 9 out of 10 people on the island do not own shares in the coconut farm. The 1 owner of the farm can sell shares in it and increase his cash position with which he can then…well, buy more milk. But how much more milk could he want to buy when he can only consume 2 coconut’s worth a day?

Applied to the contemporary global economy, the frenzy around nominal growth, valuations and budget deficits misses the fundamental point of finance-based economics: money and credit can grow in leaps and bounds while consumer demand can only grow linearly. The increase in money and credit supply may drive up the apparent valuations of dairy farms, but no amount of new money and credit supply can increase the global demand for milk beyond its natural growth rate. A billionaire does not buy 1,000 times more milk, computers or medical care than a millionaire, who in turn does not buy a million times more of these items than a pauper (or the government on behalf of the pauper).

We repeat: the “debt problem” is a currency problem and the currency must and will collapse. The global monetary system exists at the pleasure of the Fed, which legally exists at the pleasure of Congress, which as we have learned only has the political will to control the Fed at the pleasure of the Fed’s shareholder banks. It is the Fed and nothing else that determines the solvency of Treasury. Analogously, it is the Fed that ensures the ultimate solvency of the fractionally-reserved banking system – the system that shorts dollars via perceived “lending” today and covers those dollars once devalued as the Fed creates them tomorrow. Ultimately, Congress, the Fed and Wall Street will have to answer to the masses that buy milk and pay and staff its military.

There is a light at the end of the tunnel that is both another train and, leaving emotions aside, an investment opportunity for the willing and able. This is change we can all believe in, and it seems closer than most think.

1 Walter Becker and Donald Fagen; Steely Dan; “Change of the Guard”; Can’t Buy A Thrill; 1972 MCA Music Publishing

2 M3 provided by John Williams

3 Walter E. Spahr, G.C. Weigand, Editor; “Our Irredeemable Currency System”; Committee for Monetary Research and Education Inc.; Monetary Tract number 15; June 1976

4 Financial News; July 11, 2011; “Central Banks Can’t Paper Over the Economy”; Benn Steil, Manuel Hinds, Paul Swartz;

5 We calculate the Shadow Gold Price by dividing the US Monetary Base by US official gold holdings, as was done during the Bretton Woods regime from 1945 to 1973. Presently, the Monetary Base approximates $2.66 trillion and official gold holdings approximate 261 million troy ounces, meaning the SGP would be about $9,250/ounce.

6 Courtesy of ShadowStats.com;

7 Barron’s; July 18, 2011; Alan Abelson quoting Stephanie Pomboy of MacroMavens.

8 Jason Zweig; Wall Street Journal; July 23-24, 2011