by Economist

By engulfing Italy, the euro crisis has entered a perilous new phase—with the single currency itself now at risk

FOR more than a year the euro zone’s debt drama has lurched from one nail-biting scene to another. First Greece took centre stage; then Ireland; then Portugal; then Greece again. Each time European policymakers reacted similarly: with denial and dithering, followed at the eleventh hour with a half-baked rescue plan to buy time.

This week the shortcomings of this muddling-through were laid bare (see

article). Financial markets turned on Italy, the euro zone’s third-biggest economy, with alarming speed. Yields on ten-year Italian bonds jumped by almost a percentage point in two trading days: on July 12th they breached 6%, their highest since the euro was created. The Milan stockmarket slumped to its lowest in two years. Though bond yields subsequently fell back, the debt crisis has clearly entered a new phase. No longer confined to the small peripheral economies of Greece, Ireland and Portugal, it has hurdled over Spain, supposedly next in line, and reached one of the euro zone’s giants. All its members, but especially Germany, face a stark choice.

Consider the stakes. Italy has the biggest sovereign-debt market in Europe and the third-biggest in the world. It has €1.9 trillion ($2.6 trillion) of sovereign debt outstanding, 120% of its GDP, three times as much as Greece, Ireland and Portugal combined—and far more than the €250 billion or so left in the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), the currency club’s rescue kitty. Default would have calamitous consequences for the euro and the world economy. Even if the more likely immediate prospect is sustained stress in the Italian bond market, that will surely prompt investors to flee European assets, making the continent’s recovery ever harder. Meanwhile in the background there is the absurd pantomime of Barack Obama and congressional Republicans feuding over how to raise the federal government’s debt ceiling to stave off an American “default” (see

article). That may have distracted American investors briefly; once they realise how much is at stake in Italy, it will not help.

From Rome to Brussels, Frankfurt and Berlin

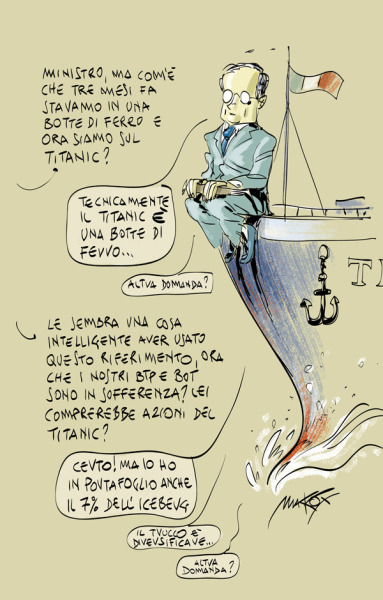

The proximate cause of this week’s scare lies in Italian politics, and a row in which Silvio Berlusconi, the prime minister, hurled playground insults at Giulio Tremonti, the finance minister, over a new austerity budget. Add in the underlying concerns about the Italian economy’s feeble growth rate, and investors are understandably worried about the Italian government’s ability to shoulder its huge debt.

In theory, these concerns should be easy for a grown-up government to address. After all, Italy, for all its faults, is not a big Greece. Its debt burden has been high but stable for years. Its primary budget (ie, before interest payments) is in surplus. It has a record of cutting spending and raising taxes if it needs to do so: in 1997, when it was trying to get into the euro, its primary surplus was 6% of GDP. By European standards its banks are decently capitalised. High private saving means that much sovereign borrowing is funded at home.

In practice, though, there is seldom a clear line between illiquidity and insolvency: if the price Italy must pay to borrow rises high enough for long enough, its debt will eventually spiral out of control. And Italy’s prospects are being overwhelmed by the contradictions and uncertainties in Brussels, Frankfurt and Berlin, where respectively the Eurocrats, the European Central Bank (ECB) and Germany’s chancellor, Angela Merkel, have all vainly tried to follow two contradictory goals—namely, avoiding any formal default on Greek debt, while also avoiding an open-ended transfer from richer European countries to the insolvent periphery (see

article).

To be fair to Mrs Merkel and Europe’s other leaders, they have not chosen to muddle through merely out of cowardice, though there has been plenty of that, but because the euro-zone countries are profoundly divided. They cannot agree on who should bear the cost of today’s crisis: should it be creditors (through a write-down), debtors (through austerity) or the Germans (through transfers to the south)? And they have not decided whether the long-term answer is a fiscal union, or not. Investors are thus unclear about how badly they may be hit. With Europeans in such a muddle over little Greece, no wonder investors are so terrified by big Italy.

Cometh the hour, cometh the Eurobond

What is to be done? This newspaper has long argued that muddling-through must be replaced by a comprehensive strategy based on three components: debt reduction for plainly insolvent countries; a recapitalisation of the European banks that will suffer from that restructuring; and the building of a firewall between the insolvent and the rest.

Debt reduction must begin with Greece, the country that is most obviously bust. However the restructuring is pitched, Greece will be in default, so a plan to recapitalise banks hit badly by this, starting with Greece’s own, will be needed too. The results of stress tests, due on July 15th, should show how much more help is required. There may have to be a similar restructuring for Portugal and Ireland.

Explore our interactive guide to Europe's troubled economies

Explore our interactive guide to Europe's troubled economies

The task of building a firewall around the solvent core, including Spain and Italy, has to be shared between the countries at risk and the euro zone as a whole. Italy needs to pass its budget speedily—and also push through long overdue structural reforms. Its challenges are not only, or even mainly, about fiscal austerity, but about making the economy grow. As for the euro zone, short-term help may have to come from the ECB buying Italian bonds (difficult politically because the next head of the ECB will be Mario Draghi, the boss of Italy’s central bank). Soon though the euro zone may well have to expand the EFSF and allow it to issue jointly guaranteed “Eurobonds”.

That is a huge political leap—especially for Mrs Merkel. Germany is firmly opposed to any solution that could imply open-ended transfers to feckless southerners; so are several other northern European countries, not least because guaranteeing others may raise their own borrowing costs. It is not a pleasant option. But the alternative could be the end of the euro. That is the horrible lesson of this week.