I am sure the Euro will oblige us to introduce a new set of economic policy

instruments. It is politically impossible to propose that now. But some day

there will be a crisis and new instruments will be created.”

- Romano

Prodi, EU Commission President, December 2001

Prodi and the other leaders who forged the

euro knew what they were doing. They knew a crisis would develop, as Milton

Friedman and many others had predicted. They accepted that as the price of

European unity. But now the payment is coming due, and it is far larger than

they probably thought.

This week we turn our eyes first to Europe

and then the US, and ask about the possibility of a yet another credit crisis

along the lines of late 2008. I then outline a few steps you might want to

consider now rather than waiting until the middle of a crisis. It is possible we

can avoid one but, as I admit, whether we do (and the extent of such a crisis)

depends on the political leaders of the developed world (the US, Europe, and

Japan) making the difficult choices and doing what is necessary. And in either

case, there are some areas of investing you clearly want to avoid. Finally, I

turn to that watering-hole favorite, the weather, and offer you a window into

the coming seasons. Can we catch a break here? There is a lot to cover, so we

will jump right in.

The

Consequences of Austerity

The markets are pricing in an almost 100%

certainty of a Greek default (OK, actually 91%), and the rumors in trading

circles of a default this weekend by Greece are rampant. Bloomberg (and everyone

else) reported that Germany is making contingency plans for the default. Of

course, Greece has issued three denials today that I can count. I am reminded of

that splendid quote from the British 80s sitcom, Yes, Prime Minister: Never believe anything until its

been officially denied.

Germany is assuming a 50% loss for their

banks and insurance companies. Sean Egan (head of very reliable bond-analyst

firm Egan-Jones) thinks the ultimate haircut will be closer to 90%. And that is

just for Greece. More on the contagion factor below.

The existence of a Plan B underscores

German concerns that Greeces failure to stick to budget-cutting targets

threatens European efforts to tame the debt crisis rattling the euro. German

lawmakers stepped up their criticism of Greece this week, threatening to

withhold aid unless it meets the terms of its austerity package, after an

international mission to Athens suspended its report on the countrys

progress.

Greece is on a knifes edge, German

Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble told lawmakers at a closed-door meeting in

Berlin on Sept. 7, a report in parliaments bulletin showed yesterday. If the

government cant meet the aid terms, its up to Greece to figure out how to get

financing without the euro zones help, he later said in a speech to

parliament.

(There is an over/under betting pool in

Europe on whether Schaeuble remains as Finance Minister much longer after this

weekends G-7 meeting, given his clear disagreement with Merkel. I think I take

the under. Merkel is tough. Or maybe he decides to play nice. His press doesnt

make him sound like that type, though. They are playing high-level hardball in

Germany.)

Anyone reading my letter for the last

three years cannot be surprised that Greece will default. It is elementary

school arithmetic. The Greek debt-to-GDP is currently at 140%. It will be close

to 180% by years end (assuming someone gives them the money). The deficit is

north of 15%. They simply cannot afford to make the interest payments. True

market (not Eurozone-subsidized) interest rates on Greek short-term debt are

close to 100%, as I read the press. Their long-term debt simply cannot be

refinanced without Eurozone bailouts.

Was anyone surprised that the Greeks

announced a state fiscal deficit of 15.5 billion for the first six months of

2011, vs. 12.5 billion during the same period last year? What else would you

expect from increased austerity? If you reduce GDP by as much as Greece

attempted to do, OF COURSE you get less GDP and thus lower tax revenues. You

cant do it at 5% a year, as I have pointed out time and time again. These are

the consequences of allowing debt to get too high. It is the Endgame.

[Quick sidebar: If (when) the US goes into

recession, have you thought about what the result will be? A recession of course

means lower GDP, which will mean higher unemployment. That will increase costs

due to increased unemployment and other government aid, and of course lower

revenues as tax receipts (revenues) go down. Given the projections and path we

are currently on, that means even higher deficits than we have now. If Obama has

his plan enacted, and if we go into a recession, we will see record-level

deficits. Certainly over $1.5 trillion, and depending on the level of the

recession, we could scare $2 trillion. Think the Tea Party will like that?

Governments have less control than they think over these things. Ask Greece or

any other country in a debt crisis how well they predicted their budgets.]

The Greeks were off by over 25%. And they

are being asked to further cut their deficit by 4% or so every year for the next

3-4 years. That guarantees a full-blown depression. And it also means lower

revenues and higher deficits, even at the reduced budget levels, which means

they get further away from their goal, no matter how fast they run. They are now

in a debt death spiral. There is no way out, short of Europe simply bailing them

out for nothing, which is not likely.

Europe is going to deal with this Greek

crisis. The problem is that this is the beginning of a string of crises and not

the end. They do not appear, at least in public, to want to deal with the

systemic problem of too much debt in all the peripheral countries.

Without ECB support, the interest rates

that Italy and Spain would be paying would not be sustainable. I can see a path

for Italy (not a pretty one, but a path nonetheless) but Spain is more

difficult, given the weakness of its banks and massive private debt. These are

economies that matter.

How do they get out of this without a debt

crisis on the scale of 2008? By coming to grips with the problem. Germany is

apparently doing that this weekend, by preparing to use the money it was going

to pour into Greece to shore up its own banks. That is a much better plan. But

as a well-researched report (by Stephane Deo, Paul Donovan, and Larry Hathaway

in the London office – kudos, guys!) from UBS shows, solving the problem will be

very costly. The next few paragraphs are from their introduction.

Euro

Break-Up The Consequences

The

Euro should not exist (like this)

Under the current structure and with the

current membership, the Euro does not work. Either the current structure will

have to change, or the current membership will have to change.

Fiscal confederation, not break-up

Our base case with an overwhelming

probability is that the Euro moves slowly (and painfully) towards some kind of

fiscal integration. The risk case, of break-up, is considerably more costly and

close to zero probability. Countries cannot be expelled, but sovereign states

could choose to secede. However, popular discussion of the break-up option

considerably underestimates the consequences of such a move.

The

economic cost (part 1)

The cost of a weak country leaving the

Euro is significant. Consequences include sovereign default, corporate default,

collapse of the banking system and collapse of international trade. There is

little prospect of devaluation offering much assistance. We estimate that a weak

Euro country leaving the Euro would incur a cost of around 9,500 to 11,500 per

person in the exiting country during the first year. That cost would then

probably amount to 3,000 to 4,000 per person per year over subsequent years.

That equates to a range of 40% to 50% of GDP in the first year.

The

economic cost (part 2)

Were a stronger country such as Germany to

leave the Euro, the consequences would include corporate default,

recapitalization of the banking system and collapse of international trade. If

Germany were to leave, we believe the cost to be around 6,000 to 8,000 for

every German adult and child in the first year, and a range of 3,500 to 4,500

per person per year thereafter. That is the equivalent of 20% to 25% of GDP in

the first year. In comparison, the cost of bailing out Greece, Ireland and

Portugal entirely in the wake of the default of those countries would be a

little over 1,000 per person, in a single hit.

The

political cost

The economic cost is, in many ways, the

least of the concerns investors should have about a break-up. Fragmentation of

the Euro would incur political costs. Europes soft power influence

internationally would cease (as the concept of Europe as an integrated polity

becomes meaningless). It is also worth observing that almost no modern fiat

currency monetary unions have broken up without some form of authoritarian or

military government, or civil war.

Welcome to the Hotel California

Welcome to the Hotel California

Such a lovely place

Such a lovely face

They livin it up at the Hotel California

What a nice surprise, bring your alibis

Last thing I remember, I was running for

the door

I had to find the passage back to the place I was

beforeRelax, said the night man, We are programmed to

receive. You can check out any time you like, but you can

never leave!

- The Eagles, 1977

You can disagree with the UBS analysis in

various particulars, but what it shows is that there is no free lunch. It is not

a matter of pain or no pain, but of how much pain and how is it shared. And to

make it more difficult, breaking up may cost more than to stay and suffer, for

both weak and strong countries. There are no easy choices, no simple answers.

Like the Hotel California, you can check in but you cant leave! There are

simply no provisions for doing so, or even for expelling a member.

The costs of leaving for Greece would be

horrendous. But then so are the costs of staying. Choose wisely. Quoting again

from the UBS report:

the only way for a country to leave the

EMU in a legal manner is to negotiate an amendment of the treaty that creates an

opt-out clause. Having negotiated the right to exit, the Member State could

then, and only then, exercise its newly granted right. While this superficially

seems a viable exit process, there are in fact some major obstacles.

Negotiating an exit is likely to take an

extended period of time. Bear in mind the exiting country is not negotiating

with the Euro area, but with the entire European Union. All of the legislation

and treaties governing the Euro are European Union treaties (and, indeed, form

the constitution of the European Union). Several of the 27 countries that make

up the European Union require referenda to be held on treaty changes, and

several others may choose to hold a referendum. While enduring the protracted

process of negotiation, which may be vetoed by any single government or

electorate, the potential secessionist will experience most or all of the

problems we highlight in the next section (bank runs, sovereign default,

corporate default, and what may be euphemistically termed civil unrest).

Leaving abruptly would result in a lengthy

bank holiday and massive lawsuits and require the willingness to simply thumb

your nose in the face of any European court, as contracts of all sorts would

have to be voided. The Greek government would have to conveniently pass a law

that would require all Greek businesses to pay back euro contracts in the new

drachma, giving cover to their businesses, who simply could not find the euros

to repay. But then, what about business going forward?

Medical supplies? Food? the basics? You

have to find hard currencies for what you dont produce in the country. Greece

is not energy self-sufficient, importing more than 70% of its energy needs. They

have a massive trade deficit, which would almost disappear, as who outside of

Greece would want the new drachma? Banking? Parts for boats and business

equipment? The list goes on and on. Commerce would slump dramatically,

transportation would suffer, and unemployment would skyrocket.

If Germany were to leave, its export-driven

economy would be hit very hard. It is likely that the new mark would

appreciate in value, much like the Swiss Franc, making exports from Germany even

more costly. Not to mention potential trade barriers and the serious (and

probably lengthy) recession that many of their export and remaining Eurozone

trade partners would be thrown into. And German banks, which have loaned money

in euros, would have depreciating assets and would need massive government

support. (Just as they do now!)

Can a crisis be avoided? Yes. But that does

not mean there will be no pain. We can avoid a debt debacle in the US, but doing

so will mean reducing debt every year for 5-6 years in the teeth of a

slow-growth economy and high unemployment. It will require enormous political

will and mean many people will be unemployed longer and companies will be

lost.

Ray Dalio and his brilliant economics team

at Bridgewater have done a series of reports on a plan for Europe. Basically, it

involves deciding which institutions must be saved (and at what cost) and

letting the rest simply go their own way. If they are bankrupt, then so be it.

Use the capital of Europe to save the important institutions (not shareholders

or bondholders). Will they do it? Maybe.

The extraordinarily insightful and

brilliant John Hussman recently wrote on a similar theme. He is a must-read for

me. Quoting:

The global economy is at a crossroad that

demands a decision whom will our leaders defend? One choice is to defend

bondholders – existing owners of mismanaged banks, unserviceable peripheral

European debt, and lenders who misallocated capital by reaching for yield and

fees by making mortgage loans to anyone with a pulse. Defending bondholders will

require forced austerity in government spending of already depressed economies,

continued monetary distortions, and the use of public funds to recapitalize poor

stewards of capital. It will do nothing for job creation, foreclosure reduction,

or economic recovery.

The alternative is to defend the public by

focusing on the reduction of unserviceable debt burdens by restructuring

mortgages and peripheral sovereign debt, recognizing that most financial

institutions have more than enough shareholder capital and debt to their ownbondholders to absorb losses without

hurting customers or counterparties but also recognizing that properly

restructuring debt will wipe out many existing holders of mismanaged financials

and will require a transfer of ownership and recapitalization by better

stewards. That alternative also requires fiscal policy that couples the

willingness to accept larger deficits in the near term with significant changes

in the trajectory of long-term spending.

In game theory, there is a concept known

as Nash equilibrium (following the work of John Nash). The key feature is that

the strategy of each player is optimal, given the strategy chosen by the other

players. For example, I drive on the right / you drive on the right is a Nash

equilibrium, and so is I drive on the left / you drive on the left. Other

choices are fatal.

Presently, the global economy is in a

low-level Nash equilibrium where consumers are reluctant to spend because

corporations are reluctant to hire; while corporations are reluctant to hire

because consumers are reluctant to spend. Unfortunately, simply offering

consumers some tax relief, or trying to create hiring incentives in a vacuum,

will not change this equilibrium because it does not address the underlying

problem. Consumers are reluctant to spend because they continue to be

overburdened by debt, with a significant proportion of mortgages underwater,

fiscal policy that leans toward austerity, and monetary policy that distorts

financial markets in a way that encourages further misallocation of capital

while at the same time starving savers of any interest earnings at all.

We cannot simply shift to a high-level

equilibrium (consumers spend because employers hire, employers hire because

consumers spend) until the balance sheet problem is addressed. This requires

debt restructuring and mortgage restructuring. While there are certainly

strategies (such as property appreciation rights) that can coordinate

restructuring without public subsidies, large-scale restructuring will not be

painless, and may result in market turbulence and self-serving cries from the

financial sector about global financial meltdown. But keep in mind that the

global equity markets can lose $4-8 trillion of market value during a normal bear market. To

believe that bondholders simply cannot be allowed to sustain losses is an

absurdity. Debt restructuring is the best remaining option to treat a spreading

cancer. Other choices are fatal.

You think the worlds central banks and

main institutions are not worried? They are pulling back from bank debt in

Europe, as are US money-market funds. (Note: I would check and see what your

money-market funds are holding how much European bank debt and to whom? While

they are reportedly reducing their exposure, there is some $1.2 trillion still

in euro-area institutions that have PIIGS exposure.)

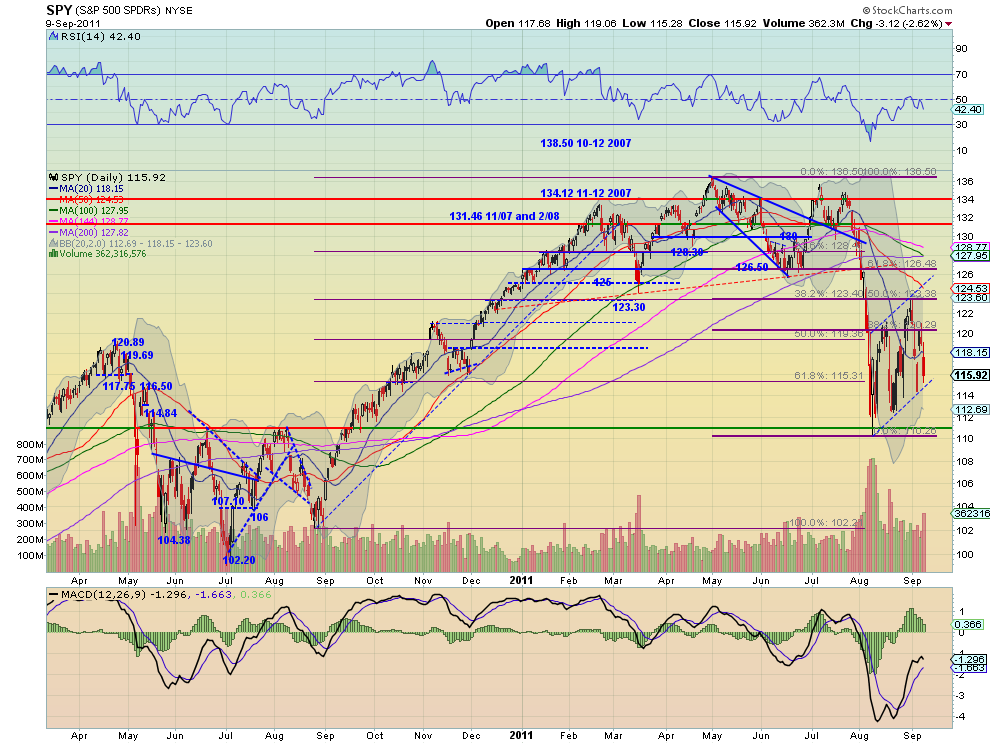

Look at the following graph from the St.

Louis Fed. It is the amount of deposits at the US Fed from foreign official and

international accounts, at rates that are next to nothing. It is higher now than

in 2008. What do they know that you dont?

The

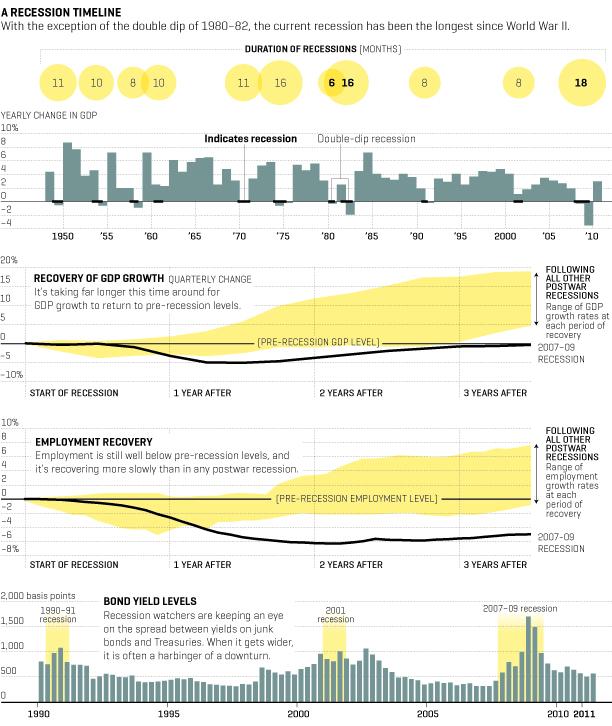

Slow March to Recession in the US

Until there is a real crisis in Europe, the

US will continue on its path of slower growth. Economists who base their

projections on past history will not see this coming. Analysts who base their

earnings estimates on recent performance are going to miss it (again.) Note:

analysts, as I have written numerous times in this letter, are so very, very bad

as a group at predicting future earnings that I am amazed people pay attention

to them; but they seemingly do. They consistently miss tops and bottoms. That is

the one thing they are very good at.

John Hussman, in the same report, offers

the chart below, which is a variant on themes I have highlighted in past issues,

but with his own personal twist. It is a combination of four Fed indices and

four ISM reports. And it has been reliable as a predictor of recessions – one of

which it strongly suggests we are either in or heading into.

And recent revisions to economic data

suggest that companies are going to have even more trouble making those

powerhouse earnings that are being estimated. As Albert Edwards of Societe

Generale reports this week:

at the start of 2011, productivity

trends took a remarkable turn for the worse especially compared to what was

initially reported. An initial estimate that Q1 productivity grew by 1.8% was

transformed to show a decline of 0.6%. A slight 0.7% rise in Q1 ULC (unit labor

costs) was transformed to show a staggering surge of 4.8%! In addition to that

4.8% rise, ULC rose a further 2.2% in Q2. But the news gets even worse Last week

the BLS revised the ULC rise in Q2 up from 2.2% to 3.3% QoQ. US non-farm

business unit labor costs are now rising by 2% yoy. That is very bad news for

profits. Bad news for equities. And because the pace of ULC is a key driver of

inflation (upwards in this instance), it is bad news for an increasingly

criticized and divided Fed.

Preparing for a Credit Crisis

There is so much that could push us into

another 2008 Lehman-type credit crisis. As I say, it is not a given, but the

possibility should be on your radar screen. Lehman may have been the straw that

broke the camel’s back, but there were a lot of other problems. Prior to 2008,

we had seen several large companies in the financial world simply disappear.

REFCO comes to mind. Not a whimper in the markets. But Lehman was one of a dozen

problems all over the world resulting from the larger subprime crisis. Howard

Marks of Oaktree writes about simultaneous problems in the markets and what

happens:

Markets usually do a pretty good job of

coping with problems one at a time. When one arises, analysts analyze and

investors reach conclusions and calmly adjust their portfolios. But when theres

a confluence of negative events, the markets can become overwhelmed and lose

their cool. Things that might be tolerable

individually combine into an unfathomable mess whose extent and ramifications

seem beyond analysis. Market crises are chaotic, not orderly, and the

multiplicity and simultaneity of contributing causes play a big part in making

them so.

I did an interview with good friends David

Galland and Doug Casey of Casey Research yesterday. They are decidedly more

bearish than I am, so wanted an optimist to sit on their panel. But they

forced me to admit that some of my optimism depends on the probability of US

political leaders doing the right thing. Depending on your opinion about that,

you are more or less prone to think there is a crisis in our future. And while I

like to think it is not me showing a home-town bias, I think Europe has worse

problems and a tougher situation than the US. A crisis there is more likely, I

think.

But whether you want to make it 50-50 to

70-30 or (pick a number), there is a reasonable prospect of another credit

crisis. So what should you do?

First, think back to 2008. Were you liquid

enough? Did you have enough cash? If not, then think about raising that cash

now. When the crisis hits, you have to sell what you can for what you can get,

not what you want for reasonable prices.

I am personally raising more cash in my

business. I usually invest money as soon as I can. Now, I am still investing,

and you too should still put money to work in places that you think have the

potential to do well in a crisis. Go back and see what worked in 2008 and buy

more of it! Long-only funds did not work. Those that were more nimble did.

In the next crisis, opportunities to buy

assets on the cheap will grow, so having some cash will make it easier to buy

things you want to own for the next 10-20 years, whether income-producing or

just something you want for fun.

Think through your portfolio. In 2008 I

watched investors liquidate solid funds, or sell off assets at fire-sale prices,

because that was the only way they could raise cash, when that was the time to

invest more, not redeem. Make sure you are the strong hand.

Understand, I am not saying sell your

conviction stocks. I have some and am buying more. But no index funds, no

long-only, unhedged funds. I make very specific choices when it comes to

long-only investments that I am looking to hold over and beyond a ten-year

horizon. And those are risks I want to take (at least today).

I do not want to own anything that looks

like an index fund or long-only mutual fund. Think 2008. I want funds and

managers that have an edge and have a hedge, preferably both.

I would not be long money-center bank

stocks or bonds, not in the US and especially not in Europe. I have had private

off-the-record conversations with Republican leaders. There is simply no

willingness to do another TARP-like bailout of bondholders and shareholders. I

believe them. As Hussman suggested, this time bondholders will lose. I just

dont know which ones will be ready, and there are lots of other places to

deploy assets. If you feel you have some special insight, then be my guest; but

I just see too much risk for the potential reward, especially in large bank

bonds that pay so little. That is not to say they are all equally bad

certainly not the regionals with less exposure to Europe. But do your

homework.

(Caveat: I do think even the GOP leaders

will have to cave in and allow the government to be debtor-in-possession of

the too-big-to-fail banks we allowed to exist under the really bad financial

bill called Dodd-Frank, which needs to be repealed and replaced. We have to

preserve the system, but not shareholders and bondholders, who will lose this

time.)

Think through your business. Banking

relationships are not what they used to be. Spend time now getting commitments.

Remember the odd spike in 2008 in bank lending? It was from credit lines being

drawn down. But no one got new lines at the time. What can you do if sales get

tough? What can you do to increase market share when your competitors start to

pull back? The winners in 2008-09 were the companies that increased innovation

and did not pull back (according to a Boston Consulting Group survey).

If you plan correctly, the next crisis will

be an opportunity for you and not a personal crisis. And you will be better able

to help those who need it.

A special note. In a few weeks I will be

sending out an email that will contain a link to a totally free treasure trove

of business and marketing ideas you can use to keep your business at the cutting

edge, whether you are established are just starting out. It is one of those

things I can do that costs me very little, but that sometime may mean a lot to

you. I am just glad to be in the position to help a little.

I know I sound rather stark at times, but I

really dont want you to dig a hole and get in and cover yourself up. I do not.

While we are perhaps somewhat more cautious, we are also looking for ways to

grow and be more aggressive here at my business. I will keep repeating: look for

the opportunities. They are there. Just gauge your risk appropriately.