By: Andrew_McKillop

SYRIAN OIL

The role of Syria's disastrous civil war as a “tailwind” helping maintain oil prices at artificially high levels is easy to show. Claims by oil analysts that this civil war “will spillover and deflagrate the entire Middle East” bump up prices. The same applies to Egypt, the Arab world's biggest country now potentially facing the risk of civil war. With imagination, the contagion talk can be extended to Libya, Tunisia, the Yemen, Bahrain, the other Gulf states, and other Mid East and North African countries. The talk helps nudge up day traded prices for Brent or WTI by 50 cents or a dollar, quite regularly, but the risk and fear premium on Arab oil is highly uncertain. When we drill down to strict net export surplus fundamentals – production versus national oil demand - any claims that Syria, Egypt, the Yemen or other countries, except Libya, Algeria, Iraq and the Gulf states, are more than tiny exporters probably moving towards net oil importer status, are very hard to defend. This is a political risk premium.

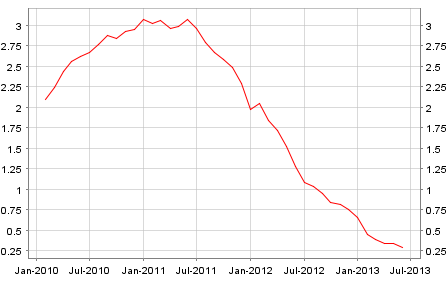

Syria's “glory days” as a small net exporter are already well in the past.

The typical newsfeed concocted with the aim of driving oil prices up, until the Morsi government fell in Egypt, featured “the Syrian concern” of traders that “potential region-wide supply disruption” could ensue if violence in Syria goes international. This is linked with often exaggerated reports from Iraq and Lebanon saying that Qatar-financed Al Qaeda djihadists from Iraq (and elsewhere), on the Sunni side, and Iraqi Shia as well as Iran-financed Hezbollah fighters, on the Shia side, are “flocking to fight in Syria”. The picture painted is of massive sustained armed conflict but in recent weeks, in fact, the fighting has diminished, and the Syrian massacre of unarmed civilians is hard to call warfare.

Whatever oil supply disruption we might fear, this will not concern Syria's own oil export supply because output has been falling for years and will go on falling, now followed by falling demand.

Looking at Egypt, the only way to use this country to talk up day traded oil prices is to wave the threat of Suez canal closure – carefully avoiding the fact that oil shipments through the canal are declining at an impressive rate – for numerous reasons. Some are for the least unexpected, and concern the satellite positioning tags for oil tankers tracked by Inmarsat. As Peter Blackhurst, head of maritime security at Inmarsat said in a December 7, 2012 interview with Reuters, “a ship can get its Global Positioning System (GPS) to give false data, including pretending to be another vessel”. Routing phantom tankers from Iran, but flagged Tanzanian, through the Suez canal when they are in fact steaming through the South China Sea to the Chinese port of Ningbo, is now a well known sanctions busting trick. Real tanker movement through the Suez canal is also falling for the simplest-possible technical factor of what maximum size of tanker the canal can accept.

While the Morsi government pondered canal fee hikes or surcharges, along with its other play-for-time strategies never followed by concrete decisions, hoping that increased revenues could serve it during IMF loan talks which were stymied, Lloyds List on 28 June reported that canal transits are continuing to decline. In first quarter 2013 there was a 10% year-on-year fall, especially marked for larger-sized vessels. The maximum sized vessels able to use the canal (Suezmax, about 160 000 tons deadweight) are charged around $1.2 million per return trip through the canal. Larger tankers, sometimes two times that size plying around the Cape to reach Europe, pay no transit fees but use more fuel.

Egypt's short-lived and small scale status as a net oil exporter, already sharply declining in the last years of Mubarak has for understandable reasons (investor retreat, civil unrest, rising domestic demand) tilted back into net importer status. This will likely continue.

TRY HARDER

Bloomberg News always goes that extra mile. In a May 28 article, its journalists worked overtime to tell us: “The civil war tearing Syria apart is threatening to erase century-old borders across the Middle East as what began as a peaceful rebellion against President Bashr al-Assad escalates into a regional religious and ethnic battle”.

This is talk aimed at adding $1 to $5 extra on the barrel! Adding Bloomberg spice to the tale, the article said that previous Anglo-French wrangling over oil concessions in the Arabian Peninsula, which ended with the Sykes-Picot secret accord of 1916 – at a time when the Turkish Ottoman empire was not yet beaten – took no account of the region's seething rivalries. The article said : “The Middle East’s entrenched ethnic, political and religious rivalries weren’t a major consideration when a well-heeled British diplomat, Sir Mark Sykes, and his French counterpart, Francois Georges-Picot, secretly redrew the region’s borders in their agreement concluded on May 16, 1916”.

Syria was however soon found to be “low prospect” for oil relative to then-independent Kurdistan and British Iraq including its Kuwait province, and American-reserved and dominated Saudi Arabia. Syria, French-dominated in the post-Ottoman carve up, became a small producer concentrated in its eastern Kurdish region, at most aiming for oil self-sufficiency. At its peak net export supply capacity in the 1990s, attained long after its independence from France in 1946, Syria's exports occasionally came near 350 000 barrels per day (0.35 Mbd) – at a time when prices rarely topped $15 per barrel. World traded oil shipped across at least one border totals about 51 Mbd.

With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1917, the two European powers, France and Britain divided Greater Syria into modern-day Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, a part of Turkey, Israel, and Jordan. The two latter were then later on split out of British Palestine. The “logic” of the frontiers, to be sure, can be radically criticized as totally absent – but comparison with the famous Balkans and their frontiers is worthwhile. Today's African frontiers can also be checked for their “logicality” or lack of it. South America's frontiers can then be compared for their “naturality”, relative to Mid East frontiers.

There was nothing inherent or natural about the post-Ottoman frontiers in the Arabian peninsula and eastern Mediterranean but the Sykes-Picot agreement only intensified an unnatural divide-and-rule patchwork set as far back as the Crusaders, Mongols and then Ottomans. Today, these “unnatural frontiers” supply copy for excited journalists at Bloomberg saying the house of cards “could fall apart in an eyeblink”. More likely, the latest unraveling that started with Arab Spring in 2011 will continue.

To be sure, apart from the “traditional flashpoint” of Israel-Palestine, another certain pressure point for change is Syria, Iraq and Kurdistan. The bad news for oil importers is that oil production, even oil reserves are far from the only issues in the region's layered and longstanding historical disputes. Rather than deliberate sabotage or military attack on oil installations, the domestic, regional and sectarian political conflict will cause “collateral damage” to oil production and export infrastructures

THE REAL PRESSURE POINTS – TO THE EAST

Turkey's relations with its own Kurds, and the Kurdish diaspora are complex and very long-dated. On occasions, Turkey will at least tacitly support Sunni Arab djihadists if they are fighting Kurdish militants in Turkish frontier regions. At the same time, Turkey is currently extending a pipeline with a capacity of 1 Mbd right up to the Kurdistan frontier – but not beyond. Turkey also runs a huge road fleet of tanker trucks, day and night importing oil from Kurdistan. The Baghdad Federal Iraqi government of Nouri al-Maliki actively disapproves of this but to no avail.

Iraqi Kurds support efforts by their Syrian counterparts to extend the present de facto, and they intend de judere Kurdish writ in Syria from today's Kurdistan in the northeast of Iraq. Inside Kurdistan, the state and nation's existence is already de judere for Kurds and any oil companies wanting to work in Kurdistan. Iraq however still claims Kurdistan is only a de facto entity, and Baghdad weakly claims it still has legitimate power over this “province”, in what it calls “northern Federal Iraq”. The likelihood or even the potential of Federal Iraq using military force to destroy independent Kurdistan must be reckoned as almost zero.

If Kurds succeed in expanding their territory out from oil-rich Iraqi Kurdistan, to Syrian Kurdistan, this will certainly set an increased challenge to the integrity of Iraq as well as Syria. Relations between the Kurd leaders Massoud Barzani, and Jalal Talabani symbolize Kurdish domestic political divides. Both are Kurd but the second is the official president of the Governing Council of Federal Iraq since April 2005. Their relations are so complex we can summarize them by saying that both, or either, are able to have a meeting with whatever US president is presently in office, whenever they want.

More simply, both aim for Kurdish independence. How they obtain it, how Syria and Iraq are “carved up” to create an enlarged Kurdistan is only one minor factor among the several factors driving the “car bomb war of Iraq”, that has reached deadly intensity since early 2013. Massoud Barzani can be called relatively Iran-friendly and Jalal Talabani relatively Saudi-friendly. Kurds can be called generally and relatively pragmatic and patient, but their patience since the 1923 “de-recognition” of Kurdistan during the Versailles Treaty conference series, by the Allied victors, in deference to Turkey, is now very limited and can become a war motive.

The political context has also moved outside of “pure sectarian lines”, since about 2003. The Middle East patchwork, today, is now responding less to theological distinctions sealed in Sunni-Shia sectarian conflict, and has moved more towards very concrete political and economic strategic interests. The case of Kurdistan is a major example, but even the mass street protests against Mohamed Morsi's failed government in Egypt can be taken as example of this trend. Sectarian Sunni-Shia conflict is not a major part of the Egyptian political conflict, either at present or in the future.

At the same time the probable or possible death throes of the Assad regime in Syria is now focused on entirely Alawite security interests – notably securing a corridor from Damascus through Homs to the Mediterranean coast enabling the home area of Assad’s Alawites to feel it is in security. This area includes the port city of Tartus, home to Russia’s only naval base in the region. Russia's real interests in Syria are however hard to fathom and could or may be related to its own domestic struggle against Sunni extremists, for example in Daghestan and Chechnya using the 'Al Qaeda' brand name. Several alternate options are available, for describing Russian Middle East policy.

US AND WESTERN POSTURING

Until very recently, in fact until 2011, Western posturing about regional geopolitics was fixated by and rooted in the 1948 creation of Israel and non-creation of Palestine. Israel-Palestine relations were the almost sole interest, outside of oil.

John Kerry expresses ritual concern on the Syrian crisis, treated as a spinoff from Israel-Palestine posturing, most recently on May 22. He said that he feared that Syrian fighting “would lead ultimately potentially to the splitting apart of Syria itself”. Added to this, the Obama administration has also publicly worried about the territorial integrity of Lebanon and the stability of Jordan. As Kerry knows full well, Syria’s border with Lebanon is open for Hezbollah fighters who cross into Syria to guard Shia villages and fight for the Assad regime. Also including Iranian volunteers, Iranian-backed Hezbollah and Iraqi Shia are in Syria battling Sunni djidhadists affiliated with the Iraqi branch of al-Qaeda supported by the Sunni ruled petromonarchies of the Persian Gulf.

Rarely if ever noted or admitted by Western diplomats and analysts, the ultra weak Lebanese state is probably the “best-fit model” for the region. Lebanon's national integrity is so flimsy that national census data is a state secret. The population, for years, is officially given as “about 4 million” to not incite domestic political and sectarian animosities and claims. Its frontiers are porous. Different communities inside the loose federal national entity are organized differently, exactly as they were organized across the region under the 300-year hegemony of the Ottomans.

Both Iraq and Iran, as well as the Gulf states are feeling the shock waves. Exactly 10 years after the probably illegal war of George Bush and Tony Blair to topple Sunni dictator Saddam Hussein, Iraq not only faces the de facto secession of Kurdistan, but also “the car bomb war”. Attacks from Baghdad to Basra killed more than 700 people in June according to the United Nations, the highest monthly death toll since 2007. Sunni mosques have been attacked, and Shia neighborhoods have been ripped apart by car bombs. Both sides in this heavily sectarian conflict are well armed and financed, but the “novelty” in this sombre killing is that the car bomb war is now also political, as well as sectarian.

The usual argument given by Western political deciders and their listened-to analysts is that “Syria is contaminating Iraq”. The claim is that what is happening inside Syria is having a major impact inside Iraq, pushing Iraqi Sunnis to “try taking back Iraq” from the Shia majority of the oil-rich east of Iraq, and from the Sunni but non-fundamentalist Kurds. As already noted, Kurdish political action has been operated with diplomatic skill, as well as military force to push the agenda for total independence. For many observers and even some Iraqis, both Sunni and Shia, the only solution for Iraq is “the Lebanon solution” of a loose, weak central government enabling large regional and sectarian autonomy – but this is exactly not the type of Iraq that the US and UK wanted in 2003.

The same Western dreaming applies to Syria. This is despite its de facto move towards a “patchwork state” being almost admitted by al-Assad's attempt at creating the Alawaite “secure zone” in the Damascus-Homs-Tartus corridor. Eastern Syria is already de facto Syrian Kurdistan, although opposed by Sunni terrorists backed by the Gulf state Sunni autocrat regimes. These “Al Qaeda factions” hold relatively large parts of the southern desert of Syria, without oil, and could be compared with the fundamentalist Muslim separatist communities in Egypt's Sinai desert, or the early kibbutzim of Israel.

Western handwringing on Arab Spring degenerating into Sunni-Shia civil war is sure to rest vain without the right decisions being taken – but the weight of historical action and repeated inaction, and the current playacting as performed by John Kerry, make it unlikely that constructive change will occur. Sectarianism has been deepening across the Middle East and North Africa since 2000. Sunni autocracy Saudi Arabia and the Qatari petro principality have flexed their petromoney and propaganda muscles – and almost inevitably have chosen to back Sunni fundamentalist fighters, but to date have only been able to viciously crush majority Shia dissent in one tiny Sunni ruled state - Bahrain.

Across the Gulf to the east the real “elephant in the closet”, the vastly bigger state of Iran has reinforced its Shia sectarian bridges to eastern Iraq, eastern Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. At the same time, as in Turkey and Egypt, Iran is in no way exempt from street protest but to date, the massive protests that unseated Libya’s Muammar Khadafi, Tunisia's Ben Ali, and Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak followed by his Sunni Muslim Brotherhood successor Mohamed Morsi, were all successful mass protests against Sunni leaders.

THE OIL BARGAINING CHIP

Presently, US State department analysts cited by the media tend to back the concept of “continued Balkanization of Syria”, rather than outright collapse. As already noted, Syrian onshore oil is concentrated in Syrian Kurdistan, and offshore shale gas and oil potential is for the moment only that – potential. Several commentators also see Syria fragmenting like Lebanon, ending as a central government with tenuous control over some cities and some enclaves, with a patchwork of regions having more or less autonomy. Iraq is almost certainly going down the same “slope of least resistance”, and similar loose federalization would be a likely break-up model for Saudi Arabia, when or if domestic conflict developed.

The role of Syria and Iraq as models for this process are called “regional contagion” and “soft partition”, but one of the main dangers is the Western-willed concept of strong, united, national states in a region where there is no real tradition of this model. For both Europeans and Americans, with either de facto federal European administration, or de judere American federalism, the imposition of highly traditional national and even monarchic or autorcratic government models in the Middle East is very easy to criticize as an anachronism.

Oil has certainly dogged and distorted the pace of change in the Middle East and North Africa. The earliest Western geopolitical and economic strategic concept for Israel, we can note, was to provide a Mediterranean pipeline terminal point and refining hub for Arabian oil, enabling the Suez canal to be avoided. Only a few relics of that era, such as rusted remains of 10-inch diameter pipelines, still exist to mark that failed concept. Both technology, time and politics relegated this Strategic Israel concept to the wastebin. Strategic Iraq is now rapidly changing, like Syria and possibly soon Egypt.

As previously noted in this article, oil is not the be-all and end-all for domestic change in the region. For outsiders it is. Mixing the two, in an increasing number of cases is like mixing oil and water, making for even less predictable and faster change. To be sure, the region's huge dependence on food imports – Syria for some while being treated as a potential “Arab breadbasket” by Saudi strategists – makes it certain it will have to go on producing and exporting oil. The likelihood, therefore, of anything other than collateral damage to oil production and export infrastructures, during regional political change, can be considered relatively low.

See the original article >>