by Golem XIV

The present global financial ‘crisis’ began in 2007-8. It is not nearly over. And that simple fact is a problem. Not because of the life-choking misery it inflicts on the lives of millions who had no part in its creation, but because the chances of another crisis beginning before this one ends, is increasing. What ‘tools’ - those famous tools the central bankers are always telling us they have – will our dear leaders use to tackle a new crisis when all those tools are already being used to little or no positive effect on this one?

I think it is worth remembering how many financial crises we have had since the economy became globally interconnected and since we began the deregulation of finance and the roll back of all Great Depression safeguards under Reagan and Clinton. It’s also worth noticing that the causes and pattern of the various crises have an unpleasant ring of familiarity about them – as in – the bank lobbyists making sure nothing gets learned and nothing gets changed.

In the 80′s there were four financial crises: The Latin American crisis caused by those countries borrowing and the global banks agreeing to lend them far too much (too much lending to people who couldn’t afford it – check), the American Savings and Loan (S&L) crisis when American S&L’s made too many bad, long-term and leveraged loans relying on rolling over and over short-term loans to fund it all (reliance on short-term liquidity to cover massive loan books of dodgy loans – check) , and the 1987 Stock market crash when the system of global debt had its first major modern global paroxysm (systemic contagion – check) . And before the dust had even settled from that we had the Junk Bond collapse ( Too much junk – check. $400 billion in junk bonds were issued in 2013 alone). In the 90s there were two more crises (if one ignores the Mexican currency devaluation): The Asia currency crisis (a replay of the Latin Crisis with the same global banks doing the same lending to different corrupt or stupid leaders who agreed to loans on behalf of people who couldn’t afford to pay back – ie nothing learned at all - check) and the Dot Com bubble (valuations way above reality fueled by cheap money and lax lending – check). I think that’s most of the kinds of greed fueled idiocy accounted for.

If you line up the S&L, the Junk Bond and the Dot Com bubble, America has had a major home-brewed financial crisis every ten years. If you consider that none of these events happened in isolation nor limited their effects to the country of origin then we have to conclude that the global financial system is prone to crises. You can, if you see the world through resolutely libertarian glasses, blame everything on interfering governments – it matters little. The fact remains that the system as is, is unstable and run by the myopic, the greedy and the corrupt. Where they draw their salary, which side of the revolving door they happen to be on, on any day seems to me irrelevant. The worst of them don’t understand and are easily bought. The best have no concern for anyone or anything beyond their next bonus.

And here we are being led by them.

Of course saying another crisis is coming is like saying we are due a large earthquake in Southern California. True, but it doesn’t mean one is going to happen tomorrow. What I think it does mean is that we should be thinking what our leaders, what the people they work for – the global overclass – might already have in mind or have already put in place, for what they want done next time. I think it would be foolish to imagine they have not thought about it and are not putting in place the things which will close off some futures and force us into others that they prefer. They have so very much to lose and so very much more they want to gain.

The next crisis.

To know what the next crisis might look like we first have to look at the conditions today that will form its starting point. Necessarily everything from here on is speculation, nevertheless even when we can’t know what people will do and what ‘events’ will overtake us, we can, I think, discern quite a bit of the general topography, the landscape, of the future.

The first thing we should bear in mind is that however it starts, the next crisis will be another debt-crisis like the current one. This is because debt is now the global currency and global financing mechanism. Once it starts, however, one thing will be very different from the last time – this time nearly all nations are already heavily indebted. Last time they were not. And this is what changes everything for the over-class.

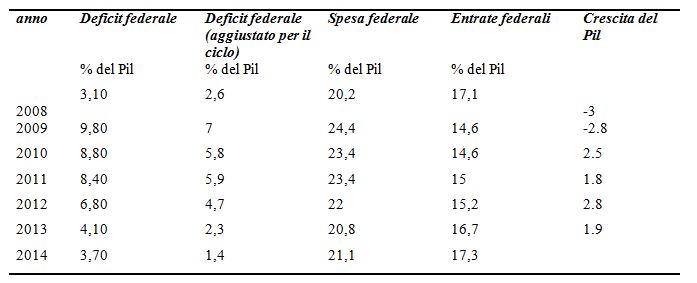

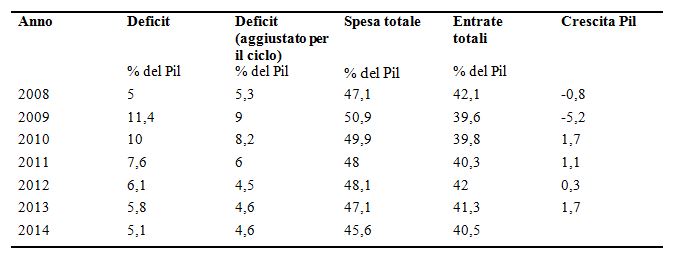

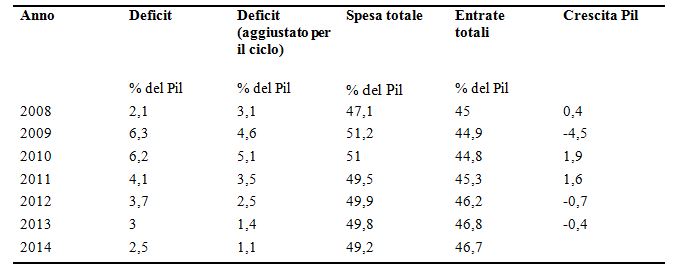

Contrary to the endless misinformation repeated at every juncture by austerity politicians and bankers alike, the debt load of most nations at the beginning of the present crisis was not already out of control before the banks blew up.

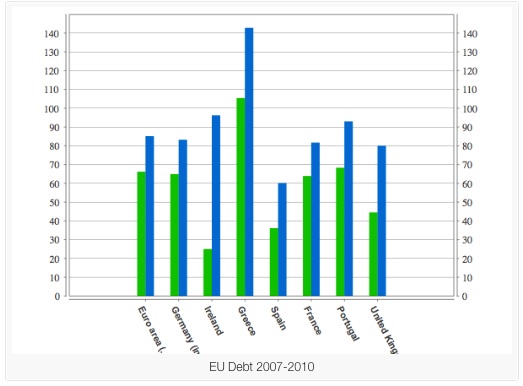

The green bars are debt as percentage of GDP before the bank bail outs and the blue bars are after. These are official Eurostat figures. Notice Ireland. Its debt to GDP was down at 27%. The ONLY thing that altered between 2007 and 2010 was the bank bails outs. Ireland’s ENTIRE debt problem is due to bailing out private banks and their bond holders. Britain’s debt almost doubled and again the ONLY thing that happened was bailing out the banks. The government claims that UK public debt was out of control due to spending on public services is just WRONG. UK government debt against GDP had not gone up in 7 years. Then when we bailed out the banks it nearly doubled. That is the fact as opposed to the propaganda of what happened and why.

If you look a little more closely into the figures for government debt levels in Europe between 2000 and 2010 the fact is that all European nations apart from Portugal were either reducing their debt-to-GDP level or at least not allowing it to grow. Most of Europe was reducing government debt to quite manageable and historically low levels. Ireland’s debt was very low (27%). Take a good long look at those two bars for Ireland. Even Spain was bringing in more in tax than it was spending. Don’t take my word for it look at the figures yourself. Almost every European country was keeping debt to GDP even or going down – before the banks were bailed out that is. The exceptions, of course, were Greece and Italy whose debt was already very high even before they bailed out their banks.

The sudden explosion of European sovereign debt is the direct and indisputable result of all our political parties deciding they would safeguard their mates’ and their own personal wealth (it is the top 10% who hold the bulk of their wealth in the financial products which would be destroyed in a bank collapse. NOT the rest of us!) by bailing out the private banks and piling their unpaid debts on to the public purse.

So whatever the trigger of the next crisis may be, they know any solution which saves the wealth and power of the over-class will have to involve piling new, private-bank bad-debts on to already indebted sovereigns and that, our leaders must be keenly aware, will not be easy to force on an already angry public. They know a whole range of the assurances they might like to give us about what must be done when the next crisis hits and how those things will undoubtably save us, will not be so easy to shove down people’s throats.

“So what,” I can hear the 1% saying, “can we do?”

Here are some thoughts on what I think they can do, will do, are already begining to do and WHY they are doing them.

The over-arching thought that I have, which shapes everything from here on, is that this crisis is no longer primarily financial; it is now political. Any solution, no matter for whose benefit, is beyond the scope of financial ‘reform’ but will depend on radical political change. In my opinion, the era of reformist politics is over. The questions are: radical change in which political direction? in whose hands? and for whose benefit?

At the moment, I believe the radical thinking is almost all being done on the 1%’s side. They may talk about fixing, but what I think they mean is changing. When Obama spoke of change, he meant it. Just not primarily for you. The 1% are not stupid. They see the need for change and intend to control it.

I think one of the cleverset things the 1% have done over the last few years is the way they have created a relentlless public discourse, via their paid political front-men and women and their media empires, to insist on the need to ‘fix’ and protect the system, and the extreme danger to us all should the system not be ‘saved’. This has served as a perfect cover for making sure that not enough people have noticed that the system is, in fact, being gutted and replaced by something that better serves the interests of the 1%. We have not been fixing the banks, we have been feeding them.

So while the 1% are thinking ahead, too many of the 99% are still like rabbits in the headlights, mesmerized and paralysed. They have been told over and over that any radical change to our present financial and political system is impossible, and if tried, would only bring disaster upon us. The 1%, on the other hand, see clearly that the present system will bring disaster upon them if it is not changed radically. They can see that it must be almost done away with entirely – in all but name. The important thing for them is that the direction of radical change benefit them and that the 99% not even realise that it is happening.

And so far it’s working – just. Just enough people continue, if grudgingly, to take refuge in a moribund political system made of parties and theories which date back to the Victorian age. The temporary triumph of the 1% is that despite the fact that no one would drive a Victorian car, nor wear Victorian shoes or clothes, they somehow feel there’s no choice but to rely on Victorian political institutions, parties and ideas. The good news is that the number who really believe this is dwindling and most of those who do, do so out of fear not faith. Which is why our present, 1% controlled politics, is increasingly about engendering fear rather than inspiring faith.

See the original article