Even as the debt crises in Europe and the United States loom large and the global economic recovery falters, inflation is making a comeback worldwide. Indeed, emerging-market economies are bracing for a serious bout of it – together with the dire political consequences that it will bring.

China’s headline consumer price index (CPI) jumped 6.4% year on year in June, reaching its highest level since July 2008. Against the background of a shaky global recovery, concerns have grown considerably over a possible hard landing for the Chinese economy, caused by monetary tightening aimed at controlling inflation.

In China, food prices account for about a third of the CPI basket, with the price of pork bearing a large weight. As a result, the CPI is jokingly called the “pork price index.” In June, pork prices rose 57% year on year, contributing nearly two percentage points to the overall inflation rate. Unfortunately, macroeconomic policy can do little about the “hog cycle” and usually should not respond to it.

While China’s inflation problem should not be exaggerated, complacency would be dangerous. Current inflation is more broad-based than it appears, regardless of the controversy surrounding the adequacy of China’s CPI basket in reflecting the reality of underlying price movements. In fact, annual increases in non-food prices accelerated to 3% in June, up from 2.9% in May. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), living expenses increased by 6.1% year on year in May. Many worry that non-food prices may rise higher.

Barring unexpected shocks, I believe that China’s inflation may peak soon. From a macroeconomic perspective, China’s current inflation is attributable both to demand-pull and cost-push factors.

Historically, inflation in China has followed GDP growth with a lag. Today’s inflationary pressures are partly the result of the lagged impact of the stimulus package that China adopted in 2009 to fight off the effects of the global financial crisis. But China’s GDP growth has already started to fall towards its potential level, which, according to the consensus view, is around 9%. In fact, most Chinese economists predicted last year that inflation would peak in early 2011.

Changes in China’s financial conditions reinforce this view. Historically, there is a lag of 8-12 months between M1 monetary growth and inflation. The growth rate of M1 started to fall in late 2009. If past experience is a reliable guide, a decline in inflation is already overdue.

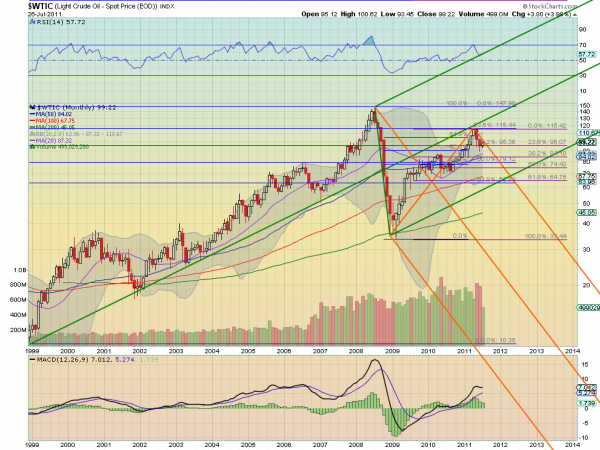

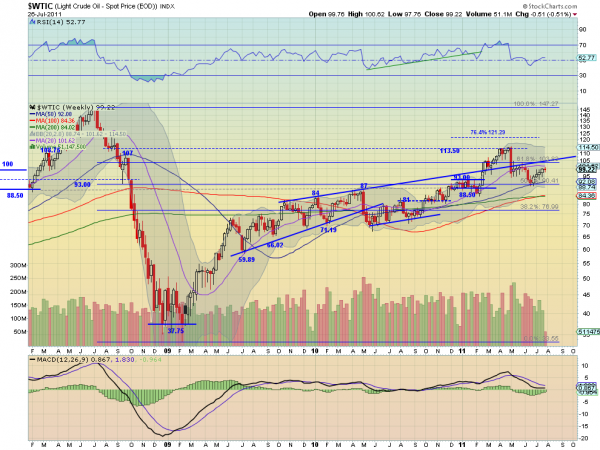

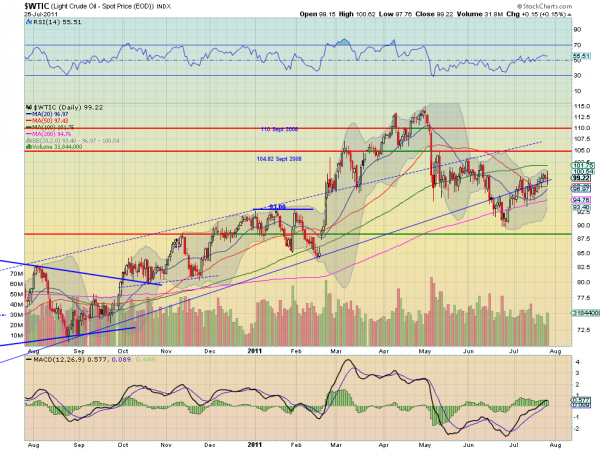

The interference of cost-push factors contributed to the unexpected persistence of inflation. The rise in commodity prices since mid-2010 – China’s commodity price index has increased by more than 100% since its 2009 low – has had an important impact. Moreover, Chinese wages have been rising rapidly.

China’s current macroeconomic situation shares many similarities with the situation that it faced in 2007 and the best part of 2008, when, owing to strong investment and export demand, GDP growth surged significantly beyond its potential. Worried about worsening inflation and a budding real-estate bubble, the People’s Bank of China (PBC, the central bank) gradually tightened its monetary stance.

Yet inflation continued to worsen, peaking at 8.7% in February 2008. The most difficult period for Chinese decision-makers was between February and September 2008, when, despite abundant signs of a softening in domestic demand, overall demand remained strong, as did inflation.

To tighten or not to tighten: that was the question. The PBC continued to tighten. But the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 brought global economic growth to a screeching halt. China’s GDP growth fell dramatically, owing to the collapse of external demand. To offset the negative shock, the Chinese government enacted a four-trillion-renminbi stimulus package, and the PBC shifted its policy stance abruptly. There is no question about the necessity for the turnaround. However, with hindsight, one might ask whether an earlier loosening by the PBC would have been wiser.

With taming inflation its top priority, the PBC has raised banks’ mandatory reserve ratio six times this year. Commercial banks must deposit with the central bank 21.5% of deposits as reserves. Recently, the PBC raised the one-year lending rate and the one-year deposit to 6.56% and 3.5%, respectively.

Currently, China’s inflation is not as bad as it was in 2007-2008. The rise in house prices has begun to stabilize, and the impact of the rise in commodity prices is tapering off.

External demand in the second half of 2011 is unlikely to be strong, owing to the shaky global recovery. The steady increase in production costs, partly attributable to high borrowing costs, is squeezing enterprises’ profit margins of – small and medium-sized enterprises in particular. Declining profits and rising enterprise bankruptcies are posing challenges to China’s monetary authority.

In view of the need for structural adjustment, the PBC should maintain a tight monetary stance. But, with a coming decline in headline inflation and mounting concerns about growth, the PBC is likely to prove a bit more accommodating in the second half of 2011.

In short, although China will miss its inflation target of 4% for this year, price growth will remain under control. In the second half of 2011, China’s growth rate could fall further, but there will be no hard landing.

China’s economic problems are more structural than cyclical. Owing to a lack of distinct progress in restructuring and rebalancing the domestic economy, the next five years will be difficult, and the window of opportunity for adjustment will close rapidly. But, viewing China’s performance in the context of the past 30 years, there is no reason to believe that the country cannot muddle through once again.

China’s headline consumer price index (CPI) jumped 6.4% year on year in June, reaching its highest level since July 2008. Against the background of a shaky global recovery, concerns have grown considerably over a possible hard landing for the Chinese economy, caused by monetary tightening aimed at controlling inflation.

In China, food prices account for about a third of the CPI basket, with the price of pork bearing a large weight. As a result, the CPI is jokingly called the “pork price index.” In June, pork prices rose 57% year on year, contributing nearly two percentage points to the overall inflation rate. Unfortunately, macroeconomic policy can do little about the “hog cycle” and usually should not respond to it.

While China’s inflation problem should not be exaggerated, complacency would be dangerous. Current inflation is more broad-based than it appears, regardless of the controversy surrounding the adequacy of China’s CPI basket in reflecting the reality of underlying price movements. In fact, annual increases in non-food prices accelerated to 3% in June, up from 2.9% in May. According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), living expenses increased by 6.1% year on year in May. Many worry that non-food prices may rise higher.

Barring unexpected shocks, I believe that China’s inflation may peak soon. From a macroeconomic perspective, China’s current inflation is attributable both to demand-pull and cost-push factors.

Historically, inflation in China has followed GDP growth with a lag. Today’s inflationary pressures are partly the result of the lagged impact of the stimulus package that China adopted in 2009 to fight off the effects of the global financial crisis. But China’s GDP growth has already started to fall towards its potential level, which, according to the consensus view, is around 9%. In fact, most Chinese economists predicted last year that inflation would peak in early 2011.

Changes in China’s financial conditions reinforce this view. Historically, there is a lag of 8-12 months between M1 monetary growth and inflation. The growth rate of M1 started to fall in late 2009. If past experience is a reliable guide, a decline in inflation is already overdue.

The interference of cost-push factors contributed to the unexpected persistence of inflation. The rise in commodity prices since mid-2010 – China’s commodity price index has increased by more than 100% since its 2009 low – has had an important impact. Moreover, Chinese wages have been rising rapidly.

China’s current macroeconomic situation shares many similarities with the situation that it faced in 2007 and the best part of 2008, when, owing to strong investment and export demand, GDP growth surged significantly beyond its potential. Worried about worsening inflation and a budding real-estate bubble, the People’s Bank of China (PBC, the central bank) gradually tightened its monetary stance.

Yet inflation continued to worsen, peaking at 8.7% in February 2008. The most difficult period for Chinese decision-makers was between February and September 2008, when, despite abundant signs of a softening in domestic demand, overall demand remained strong, as did inflation.

To tighten or not to tighten: that was the question. The PBC continued to tighten. But the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 brought global economic growth to a screeching halt. China’s GDP growth fell dramatically, owing to the collapse of external demand. To offset the negative shock, the Chinese government enacted a four-trillion-renminbi stimulus package, and the PBC shifted its policy stance abruptly. There is no question about the necessity for the turnaround. However, with hindsight, one might ask whether an earlier loosening by the PBC would have been wiser.

With taming inflation its top priority, the PBC has raised banks’ mandatory reserve ratio six times this year. Commercial banks must deposit with the central bank 21.5% of deposits as reserves. Recently, the PBC raised the one-year lending rate and the one-year deposit to 6.56% and 3.5%, respectively.

Currently, China’s inflation is not as bad as it was in 2007-2008. The rise in house prices has begun to stabilize, and the impact of the rise in commodity prices is tapering off.

External demand in the second half of 2011 is unlikely to be strong, owing to the shaky global recovery. The steady increase in production costs, partly attributable to high borrowing costs, is squeezing enterprises’ profit margins of – small and medium-sized enterprises in particular. Declining profits and rising enterprise bankruptcies are posing challenges to China’s monetary authority.

In view of the need for structural adjustment, the PBC should maintain a tight monetary stance. But, with a coming decline in headline inflation and mounting concerns about growth, the PBC is likely to prove a bit more accommodating in the second half of 2011.

In short, although China will miss its inflation target of 4% for this year, price growth will remain under control. In the second half of 2011, China’s growth rate could fall further, but there will be no hard landing.

China’s economic problems are more structural than cyclical. Owing to a lack of distinct progress in restructuring and rebalancing the domestic economy, the next five years will be difficult, and the window of opportunity for adjustment will close rapidly. But, viewing China’s performance in the context of the past 30 years, there is no reason to believe that the country cannot muddle through once again.

Yu Yongding, currently President of the China Society of World Economics, is a former member of the monetary policy committee of the Peoples' Bank of China and former Director of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of World Economics and Politics.