by Alessandro Rebucci

In some parts of the emerging world, housing markets have grown well ahead of income in recent years. US interest rates are about to rise, and international capital will revert to the center, seeking higher and safer yields. This will bring about an earthquake in housing markets at the periphery of the global financial system.

Since the 2008-09 global financial crisis, housing markets around the world have cruised at different speeds. While in many advanced economies they either contracted or stagnated, housing prices in emerging markets recovered quickly and kept rising.

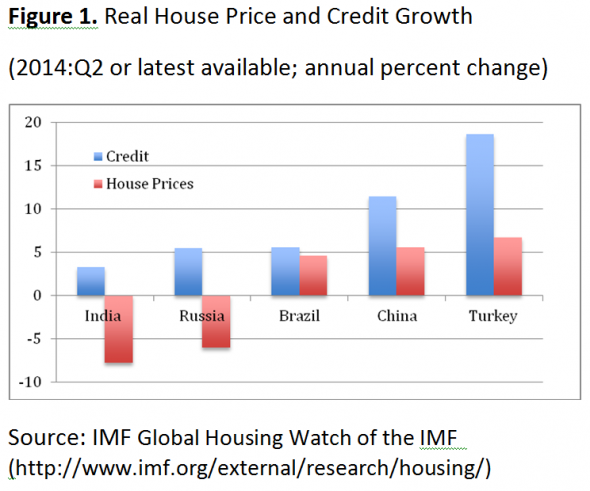

According to the Global Housing Watch of the IMF (Figure 1), for instance, house prices (and credit) in Brazil, China, and Turkey are still running well ahead of inflation, even though income growth has long slowed in these economies. Particularly worrisome in Brazil and Turkey, inflation is high and the current account deficit is quite large; these economies are still overheating and relaying on foreign borrowing to spend beyond their means. In contrast, prices in India and Russia are falling as domestic problems have already poked the housing bubble.

China’s fundamentals are seemingly more solid. But the occasional hiccups in the domestic financial systems and the erratic policy response of the central bank remind us that the ongoing transformations are challenging and far from complete. Liberalizing the financial system while rebalancing growth toward consumption with high debt and an overvalued housing market is difficult at best. It could easily turn into a systemic threat to financial stability if the easy credit policy that supports demand fails to perform the rebalancing act.

The Fed is about to raise interest rates for the first time since December 2008 when it took them to zero to fight the crisis. The US economy could be approaching full capacity and some wage pressures have already started to surface, although headline inflation remains subdued partly thanks to falling energy prices. Asset prices are at all time high while credit growth has picked up. These are all healthy signs of a rehabilitated economy capable of standing on its feet. And the Fed is worried about falling beyond the curve, repeating the mistake of 2002-04 when it raised rates too little and too late.

Historically, when the Fed tightens, capital flows reverted to the center causing earthquakes at the periphery. The ignominious Tequila crisis was preceded by a sequence of US interest rate increases, the second last and the largest of which was in November 1994. Mexico was caught off guard: after an ill-conceived attempt to defend the exchange rate earlier that year, on December 20 it capitulated under a massive speculative attack and devalued its currency in the midst of the deepest recession since the 1982 debt crisis. The banking system went under a wave of mortgage defaults triggered by the sudden increases in interest rates and unemployment. The mortgage market never recovered completely.

When capital flows out, house prices tumble, the current account balance suddenly swings into surplus, and consumption has to adjust dramatically. Loosening domestic monetary conditions and depreciating exchange rate can help cushion the blow. If borrowing is in foreign currency, however, there is only so much that can be done other than painful adjustment, like in the case of Mexico in 1994.

With limited scope for rescuing the economy after a crash, the best that can be done is to try to engineer an orderly housing correction before it is too late. Tightening the regulatory parameters of the financial system in a precautionary manner—the so-called macro-prudential policies—is one way to go. This would not only cool off housing and credit markets, but would also put them on more solid footings to face the financial earthquake that is about to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment