The US Federal Reserve talked in early summer about tapering its quantitative easing plan and raising interest rates—in part to stop investors from chasing yield into the arms of riskier loans. In the high-yield market, however, the conversation had exactly the opposite effect.

Afraid of Snakes? Perhaps You’d Prefer a Scorpion?

The shock of the Fed’s potential moves sparked a speculation-driven rise in interest rates in May and June. Because investors wanted to avoid losing money if rates head higher, they shifted from holding longer-duration bonds into holding more lower-credit-quality bonds. High-yield investors began buying CCC-rated “junk” bonds for their higher coupons.

And they’ve made money so far. But the bite from these junk bonds can be painful if the company issuing the bond runs into trouble: defaults often result in complete loss of value.

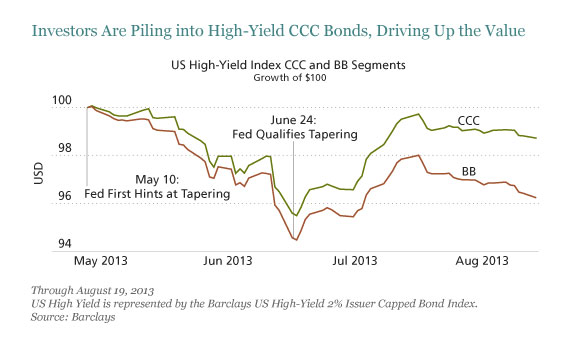

Here’s what happened. In early Maythe Fed first gave indications that it would step down its purchases—and investors immediately began selling. In late June, as investors grew increasingly agitated, Fed officials tried to calm the market with assertions that they wouldn’t act until the economy showed significant signs of strength.

That’s when CCC buyers began to make their move. Today, the yield investors require to take on CCC-rated bonds has dropped and the bonds’ value has risen versus BB-rated bonds. While prices stayed close until June 24, they diverged significantly afterwards, and from then CCC-rated bonds earned 1.5 percentage points more in total return through mid-August (display). So ironically, the safest sector of the high-yield market is now the cheapest.

Investors are thinking clearly in some respects: lower-credit-quality bonds generally improve in a rising economy and are less correlated with interest-rate movements. And in fact, CCC-rated bonds are among the few sectors to have made money in the recent fixed-income rout.

But stocking up on these lowest-quality bonds could be shortsighted in the long term. Here’s why: US companies got leaner after the 2008 crisis and reduced costs aggressively. When the recovery gained traction, they held the line on expenses. But, as the economy continues to move forward, companies will likely start to overreach, and some will get into financial trouble. So in the current part of the cycle, it’s prudent to start getting more conservative with credit, not less.

Too Much of a Good Thing May Not Be Good for You

Investors are also looking at bank loans as an alternative to long-duration bonds; their floating rates seem like a positive, but these loans offer investors little protection. And bankers are happy to turn the demand for high-yielding investments to their own advantage. In particular, the private equity market has seen an uptick in deals financed with very high-yield payment-in-kind bonds, which mean less cash is needed up front.

These can be dangerous structures in a recession or downturn.

When everyone is running away from duration risk and toward credit risk, doing the opposite may be wise. Especially in the current market cycle.

Longer-duration, higher-credit-quality bonds have gotten cheap and currently offer the best risk and return tradeoff for your money, in our analysis. And that’s a theme we’re seeing across the fixed-income world—not just in high yield.

No comments:

Post a Comment