by rcwhalen

"America’s present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy; not revolution, but restoration; not agitation, but adjustment; not surgery, but serenity; not the dramatic, but the dispassionate; not experiment, but equipoise; not submergence in internationality, but sustainment in triumphant nationality."

President Warren Harding

1920

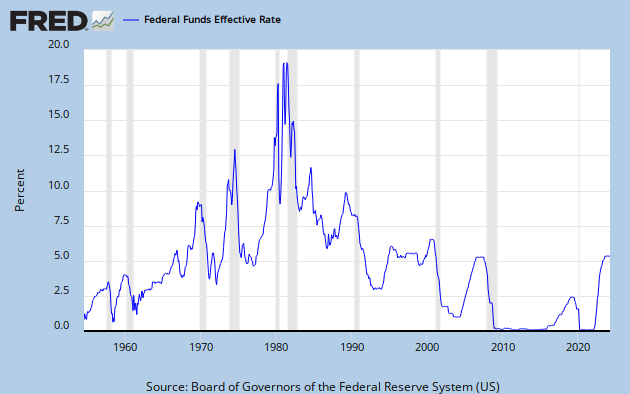

One of the themes that I hit in my 2010 book, “Inflated: How Money & Debt Built the American Dream,” is that way in which the Federal Open Market Committee has used progressively lower and lower interest rates to artificially boost economic growth. In theory the Fed is responsible for promoting full employment and price stability, but in fact the real focus of policy is the former.

One of the troubling things about the market “correction” of last week is the way in which economists, Fed officials and members of the media persist in describing the US economy as “recovering” even though the interest rate policy remains extreme. The chart above from FRED shows that, according to economists, the US economy has been out of recession for three years. But with interest rates ~ 0, is this an accurate description? Whether you talk about housing, stocks or bonds, all of these prices are a function of extreme FOMC policy.

The roots of the Fed’s extreme policy actions start in the late 1980s, when former Fed Chairman Paul Volcker was replaced by Alan Greenspan. This change in leadership at the Fed was very significant because the central bank essentially capitulated to political pressure for growth. Think of the arrival of the nominally Republican Greenspan as the final victory of the socialist tendency in American politics that starts with FDR and the New Deal.

Greenspan’s FOMC put on a good show for the public, but in substantive terms gave up on using interest rates to control inflation in the face of growing federal budget deficits and unfunded entitlements. Compared with the actions taken by the Fed following WWII and in the 1970s under Volcker, policy under Greenspan from 1987 onward was entirely accommodative and with no protest regarding swelling fiscal excesses. See “Washington & Wall Street: Volcker Challenges Bernanke on Inflation.”

My friend Roger Kubarych, who worked at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, then on Wall Street as an economist for Henry Kaufman, and most recently at the CIA, frames the issue thusly:

"In '87, with the LDC debt crisis and the failure of the thrift industry front and center in people's minds, only a few diehards were confident that the financial system was stable, or that bankers knew what they were doing. But there were penalties for pointing this out to Reagan confidantes like Walter Wriston, George Shultz, and Don Regan. So Paul Volcker was replaced by Alan Greenspan. The 90's were essentially successes for the Greenspan followers, which included 90% of the media and most of official Washington. Even the high-tech bubble and its nasty aftermath didn't quash the notion that Greenspan was the man. Dissents became almost a thing of the past (apart from the estimable Gary Stern and more quietly Ned Gramlich behind the scenes). But then came the housing & financial collapse, along with Bernanke, deference to the US Treasury on a number of issues, and a splintered FOMC that leaves the financial markets with the nagging sense that we are living through a Potemkin Village of pseudo-stability. A great many serious professionals are convinced that it is only a matter of time before the day of reckoning comes. In short, in '87 there was knowledge that much was wrong with the financial system, but that smart guys like Volcker and (while his aura lasted) Greenspan would put things right. That's not the case anymore."

Today whether you talk to people in the financial media or among the investment community, you almost never hear any recognition that we are living in an anomaly both in economic and financial terms. None of our supposed leaders at the Fed, the White House or in Congress will admit this publicly. Thus when Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke suggested that the FOMC would end the heroin drip that has been keeping the US economy growing – at least in nominal terms – the markets tanked.

This AM on CNBC, during an interview with Jed Kolko of Trulia (~ 3:50 into the interview,) one of the hosts makes the key point: “We got a real problem. If we can’t sell homes for anything but a bargain basement mortgage rate, then we’ve got a problem.”

The Fed has been using artificially low interest rates to boost economic activity for 30 years. In some respects, the end of QE* marks the culmination of that long term trend, but it also implies that a “normal” economy will look nothing like it does today. Thus when you hear economists talking about future home prices, growth or job creation, you must adjust these prognostications for an eventual “return to normalcy,” to recall the words of President Harding.

Unlike the period following WWI and WWII, when the US economy was like today operating under extreme government intervention, today we are living through the last painful adjustment to those conflicts and the resulting demographic distortions in the decades that followed.

A century ago, we had leaders who understood that price stability is more important than employment and were not afraid to make tough decisions to avoid inflation, which had been a big problem during both conflicts. Today we are led by political cowards who, in general, lack the honesty and personal integrity to tell Americans the truth about growth and inflation. I do not put Ben Bernanke into this category because he seems to have the intelligence to understand that our current economic course is “unsustainable,” to use a very overused term.

When Chairman Bernanke started to describe a world after QE in the press conference following the latest the FOMC meeting, investors fled. David Kotok, Chairman and CIO of Cumberland Advisors, puts the situation succinctly in a comment written over the weekend during our fishing trip to Maine:

"The takeaway from the group and others gathering here at Leen’s Lodge is pretty clear. Housing, finance, mortgaging, and the recovery in the US will see a setback. How severe that setback will be remains to be seen. The range of outcomes may span several hundred thousand single-family housing starts a year. The news is not good. The economy is likely to slow because of the slowdown in the housing recovery. The policy options available to the Fed are likely to become more difficult. What is the Fed going to do if housing slows and we get well under two-percent GDP growth rates because of that? What happens to the incipient recovery in terms of consumer discretion? What happens to job creation in the housing sector, which offers higher-paying jobs? Is the Fed about to repeat its 1937 mistake of too-quick tightening? In 1937 the Fed did not have to deal with the balance sheet side and escrow reserve deposit rates. Policy was made differently then. However, the ramifications of imposing a serious shock on a recovering economy may be quite similar.”

There is no greater crime in Washington today than speaking truth about the US economy in public. This is why Ben Bernanke is not being reappointed for another term as Fed Chairman. Bernanke did what was required following the 2009 credit implosion, but now he is showing signs of doing the right thing when it comes to inflation.

My guess is that President Obama probably will select his childhood friend and former Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner as the next Fed Chairman, this in an effort to keep the great pretense about "economic growth" going a little while longer. Geithner by his own admission knows nothing about economics or finance, but he certainly understands politics. Politics rather than any flavor of economics is driving Fed policy today.

No comments:

Post a Comment