By Niels Jensen

”There are four types of countries: the developed, the underdeveloped, Japan and Argentina.”

- Simon Kuznets, Nobel Laureate

When Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were assassinated in June 1914 whilst visiting the city of Sarajevo, little did the people of Argentina realise what would follow. Not only did it mean four years of death and devastation in Europe but, for the good people of the Pampas and beyond, it would also mark the beginning of a very long slide from riches to rags.

It is not my intention to pick on Argentina; however it represents a unique opportunity to analyse and understand the long-term consequences of policy mistakes. In the case of Argentina, the fact that the ruling classes were kleptocrats didn’t exactly make the situation any better.

Don’t cry for me Argentina

Now, before you accuse me of having converted to the philosophy of Karl Marx, consider the following: A century ago Argentina ranked as one of the wealthiest countries in world, behind the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia but ahead of countries such as France, Germany and Italy. Its per capita income was 92% of the G16 average; it is 43% today. Life in Argentina was good. It enjoyed the benefits of one of the highest growth rates in the world and attracted immigrants left, right and centre. Boom times galore.

Argentina’s wealth was based on agriculture, but also on its strong ties with the UK, the pre-World War I global powerhouse. Equally importantly, it understood the importance of free trade and took advantage of the relatively open markets which prevailed in the years leading to the Great War. Most importantly, though, it benefitted from, but also relied upon, enormous inflows of capital from the rest of the world. All of this is well documented in a recent piece in The Economist which you can find here.

However, World War I changed all of that. The British Empire began to lose its gloss during the period that followed. The depression of the early 1930s effectively put an end to the free trade system which Argentina relied so much on and, critically, foreign investments dried up. These factors alone do not fully explain Argentina’s demise, though. The misery was amplified by a series of policy mistakes. At the most basic level, it failed to educate its children. For a country of such wealth, it is an embarrassing fact that it had a much lower literacy rate than its peers. The land owners provided primary education but little or nothing beyond that. They had no real interest in doing so, and the government did nothing to change it.

In the post war years, as the rest of the world reduced its reliance on commodities and became more and more industrialised, Argentina got stuck in the old system. Having failed miserably to use its wealth to develop other industries, its over-reliance on commodities eventually caught up with them. Furthermore, post-World War II, as the rest of the world began to open its borders again, under the leadership of Peron, Argentina chose to go the other way and became more and more closed. A succession of military coups beginning in 1930 didn’t really help its course either.

More recently, decisions seemingly designed to please the uninformed, but having the effect of peeing off the rest of the world (such as the decision to boot Repsol out of the country), haven’t exactly done their standing in the international community any good either. All in all a fairly capacious catalogue of policy mistakes. No wonder foreign investors are not lining up to invest in the country today.

Enough about Argentina. After all, I will be going there for the very first time a few short weeks from now, and I don’t want to be turned away at the border! Sitting here in the relatively cosy surroundings of Southern England (if it weren’t for the flooding), it is tempting to conclude that we are smart enough to avoid the sorts of problems that have dragged Argentina down over the past century. At the same time, that is probably the most uneducated, and certainly the most dangerous, conclusion to reach. Time and again we have seen our political leaders demonstrate that they have spines no stronger than that of boiled spaghetti. Business partner and good friend John Mauldin often jokes that politicians are like teenagers. They opt for the easy solutions until there is no other way out. Only when their backs are firmly nailed against the wall, will they make the difficult choices. Sadly he is spot on.

The challenges facing Europe

Here in Europe we face at least two massive challenges over the next decade or two, and how they are handled will probably determine the welfare path in our part of the world for many, many years to come. At the moment our political leaders largely ignore both of them.

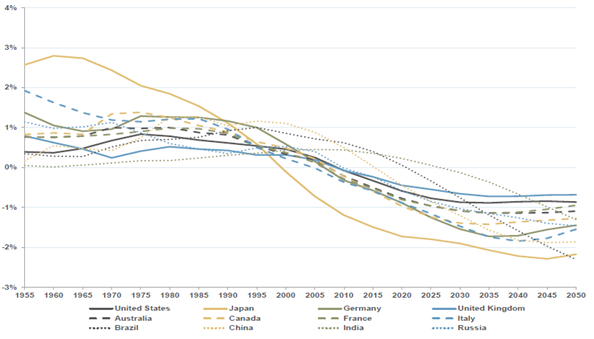

At the most basic level, economic growth is driven by population growth and improvements in productivity – i.e. how many people are there in the workforce and how much can they produce? Simple as that. Whilst productivity can, and does, vary modestly, the size of the workforce can be predicted many years out with only limited uncertainty. It is therefore possible to establish relatively precise long-term growth expectations based on demographic models. That is precisely what our friends at Research Affiliates have done (chart 1).

The picture is worrying to say the least. Most countries will be facing significant headwinds from demographic forces in the decades to come. Now, as many people ask me when I bring up this issue, why is economic growth so important? Couldn’t we all live happily in a low – even zero – growth environment? After all, isn’t Switzerland a prime example that you don’t need much economic growth to stay rich? (Switzerland has enjoyed one of the lowest growth rates in the world over the past couple of decades, yet it is one of the most prosperous.)

I have several problems with that argument, the first one being how expectations are managed by the political leadership. Precisely because the political establishment is a profession dominated by moral pygmies and mental midgets (Bertrand Russell’s words, not mine), policy makers won’t have the nerve to tell the truth, meaning that the current climate of debt financed consumption – whether in the private or public sector – could quite conceivably continue until it collapses under its own weight. As pointed out in a somewhat more diplomatic tone by the authors of the Research Affiliates paper:

“If we expect our policy elite to deliver implausible growth, in an environment in which a demographic tailwind has become a demographic headwind, they will deliver temporary outsized “growth” with debt-financed consumption (deficit spending). If we resist the necessary policy changes that can moderate these headwinds, we risk magnifying their impact.”

Chart 1: Forecasts of Economic Growth Based on Demographic Forces

Source: Research Affiliates, Mind the (Expectations) Gap, June 2013.

The second issue I have with the Switzerland argument has to do with the absolute level of debt which continues to rise despite all the talk about austerity. In simple terms, the higher the overall level of debt, the more economic growth one needs to service that debt. The debt trajectory in some of the largest countries in the world is nothing short of frightening, yet we continue to pile on more debt (chart 2). The projections provided by the Bank for International Settlements are quite obviously meant as a stark warning to politicians around the world. Do nothing and this is what will happen. You should be aware that the projected rise is a function of changing demographics; more specifically the result of the entitlement programmes that are currently in place. An end to the crisis environment we have been in since 2008 will not change the path, only the steepness of the curve.

Chart 2: Long-Term Sovereign Debt Projections

Source: Bank for International Settlements

It is pretty obvious that something will have to give. Otherwise we will end up in a situation where only a modest rise in interest rates could destroy entire countries. So, when Switzerland has been able to maintain its high living standards despite it sub-par growth path, it is at least partly down to the fact that the country, unlike most, is not heavily indebted.

The third reason Switzerland is a poor proxy for the rest Europe is the massive difference in youth unemployment. Whereas in Switzerland it is hovering around 8%, youth unemployment in the Eurozone is now 25%. Even though I have some issues with how the EU calculates youth unemployment (they back out students from the overall youth population which has the effect of dramatically reducing the denominator) there is no denying that Europe is facing an unemployment crisis of gigantic proportions.

We are at great risk of losing an entire generation of people to permanent unemployment which is nothing short of tragic. Rapid economic growth (in the range of 3-5% per annum) over an extended period of time would probably be required to bring most of these people back into the workforce but, for the reasons outlined earlier, it simply isn’t going to happen; however, that should never be used as an excuse to do nothing.

There are solutions

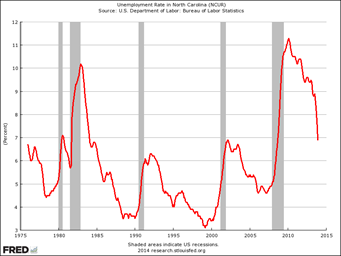

The single most potent pro-growth policy tool is deregulation. Deregulation of labour markets first and foremost but also of products markets, in particular across borders. Policy makers in North Carolina removed long-term unemployment benefits last summer. Since then the rate of unemployment has plummeted from over 11% to less than 7% (chart 3). Obviously the downward path has benefitted from an overall decline in U.S. unemployment and probably also from many people dropping out of the workforce altogether as a consequence of the loss of benefits, but the effect has been significant nevertheless.

Chart 3: Unemployment in North Carolina less National Average

Source: http://www.businessinsider.com/north-carolina-unemployment-rate-2014-1

Infrastructure spending is another powerful tool and one which I have written about in the past. If we accept that we cannot eliminate public deficits from one day to the next without creating a deep recession, we should at least aim to spend the money on infrastructure projects where the return on invested capital is measured in future economic growth and not in number of votes at the next parliamentary elections.

At the moment, policy makers seem to have forgotten that there is more than one knob to turn on the control panel. To quote the brilliant Woody Brock who is kind enough to share his insights with us and our clients:

“Monetary policy on its own will not and cannot achieve these long-overdue goals. Repeat: Fed Watchers go jump in the lake!”

Conclusion

This month’s Absolute Return Letter is a short one by my standards. I have delivered the key message. No reason to go on for much longer. Unless serious action is taken, Europe in particular (but the U.S. is not far behind) is at risk of falling into a very deep hole from which it may be extraordinarily difficult to dig itself out of. Once in, it will prove ever so hard to get out again. That is one of the key lessons learned from Argentina, even if the nature of Europe’s problems is different from those of Argentina.

Let me round this month’s letter off with a couple of investment implications:

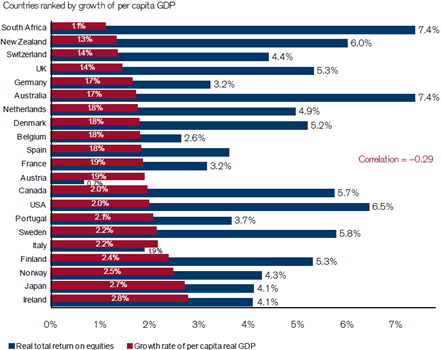

There appears to be a widespread belief amongst investors that wealth creation (here measured as GDP growth per capita) and equity returns are highly correlated. In other words, invest in those countries with the highest GDP per capita growth, and you will achieve the most attractive returns. After all, it would be a perfectly logical conclusion to arrive at. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth. Over the long term the two have actually been negatively correlated (chart 4). It could therefore prove to be a costly mistake to exclude Europe from a global equity portfolio just because you have (valid) reasons to believe that growth – and thus wealth – will stagnate in the years to come.

Chart 4: Real Equity Returns & Per Capital GDP, 1900-2013

Source: Credit Suisse, Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2014

Secondly, when it comes to managing a debt crisis of sorts, currency issuers have a significant advantage over currency users. The latter have to go outside their own country to fund their deficit, hence the risk of default if they can’t access international markets (usually the result of mis-management). Currency issuers, on the other hand, can issue unlimited amounts of IOUs in their own currency and may, as a result, avoid overt default in perpetuity. This distinction is highly significant, given the elevated levels of debt at present.

As sovereign debt continues to grow in many countries, should interest rates begin to rise, servicing the debt would take a bigger and bigger toll on public budgets. It is therefore reasonable to expect governments to collude with central banks to try and keep interest rates under control in the years to come. Now, investors are not stupid. They will look to get paid for the added risk they take, either explicitly or implicitly. If interest rates are perceived to be grossly manipulated, market mechanisms will ensure that investors will instead turn their attention to exchange rates to seek the necessary adjustments. Consequently, we expect currency markets to take the brunt of the adjustments that will have to happen over the next several years as it becomes increasingly clear who is in the ‘deep hole’ and who is not.

No comments:

Post a Comment