By JJ Abodeely

In Rob Arnott’s November 2010 piece, “The Glad Game” he asks investors to consider “Maverick Risk” as an important driver of investment outcomes:

There’s conventional volatility in returns, which introduces a risk of poor investment returns. There’s the asset/liability mismatch, which leads to a risk that we cannot cover our future obligations. And, there’s maverick risk, in which investors choose a different path than their peers, exposing them to criticism, especially when performance suffers. All three risks are hugely important. Yet, we typically focus our analytics on the first of these, simple volatility, and our behavior on the last of these, maverick risk.

The idea of “Maverick Risk” is an interesting one. We know that from a human behavioral standpoint, we are conditioned to think of being outside of the herd as “risky.” There is plenty of evolutionary logic behind this idea considering that humans have spent much of their existence as both predator and prey; there is safety in numbers. So as much as we modern humans know the value of “thinking outside the box” or “being contrarian” and as much as we value and revere those in society who are capable of going it alone or using creative or original thought– when it comes down to financial decisions, our lizard brains take over and we seek the safety of crowds. This is true for amateurs and professionals alike. This is well documented in the rapidly growing popular and academic literature on behavioral finance.

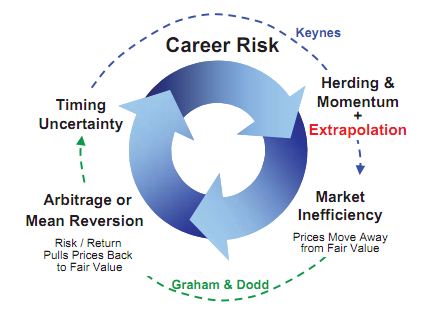

GMO takes the idea of “Career Risk” and relates it to idea that it can drive periods of over and undervaluation. As Ben Inker, the head of asset allocation at GMO was quoted as saying in a recent Advisor Perspectives article:

“The market tends to be priced in a way that if you want to try to outperform, you have to take a risk of looking like an idiot,” Inker said. To outperform, you have to deviate from your benchmark, and that increases the risk of underperformance and, in the extreme, looking like an idiot and getting fired. As a result, markets exhibit herd-like behavior, which in turn encourages momentum and other self-reinforcing behaviors, such as money flowing into whatever strategy has been doing well, Inker said. That merely ratchets up valuations within better-performing asset classes and sectors, he said, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Of course this can not continue indefinitely. Eventually prices move far enough away from fair value and the risk/return trade off becomes so one-sided, that prices get pushed back towards fair value. Consider this chart from GMO.

The Way the Investment World Goes Around: They Were Managing Their Careers, Not Their Clients’ Risk

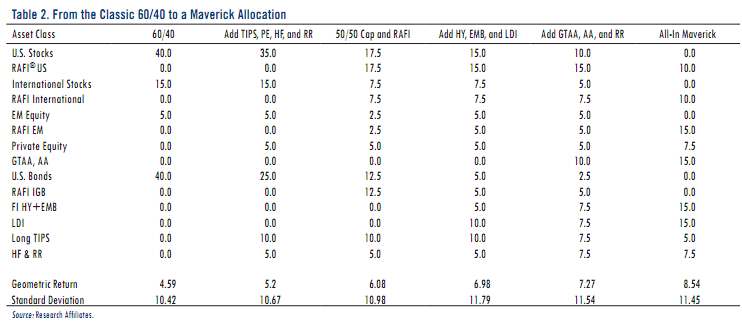

Rob Arnott suggests that by embracing Maverick Risk and deviating from the traditional 60/40 stock bond portfolio, one can add several percentage points a year to expected returns above and beyond the expected returns that are available from the valuation of traditional asset classes themselves. This is good to hear as broad equity and bond market indexes are priced to deliver very low single digit returns over the next 5-10 years, with a high likelihood of meaningful periods of negative returns. Consider my post, Expensive Markets Mean Low or Negative Prospective Returns.

The basic approaches that Arnott advocates for range from adding non-core asset classes such as emerging markets, high yield bonds, and “alternative” strategies to choosing fundamentally-weighted indexes (Research Affiliates Fundamental Index or RAFI is what they sell after all). Importantly, he advocates employing an active, dynamic, and contrarian approach to asset allocation, which presumably does not require investment in each of these asset classes or strategies at all times. It does however require that each of these asset classes and strategies are at a minimum, part of investors’ tool box, our universe of potential investments.

Research Affiliates’ Expected Returns for Various Allocations

GMO’s Inker agrees when it comes to power of truly active asset allocation to drive investment returns:

“The good news is that in the investment business there are very few people who do real asset allocation and actually move money around in an aggressive way,” Inker said. “It’s a tough thing to do and survive. The nice thing about it, and the reason why we do it, is because this means it’s an inefficiency that is not going to get arbitraged away anytime soon.”

GMO knows what they are taking about when the say that it’s a tough thing to do and survive. Their refusal to chase expensive markets in the late 1990′s meant they lost half their assets under management. HALF. 50% of their assets, 50% of their revenues, gone. They were willing to embrace Maverick or Career risk and looked like idiots for doing so. That must have been a somewhat painful experience, but perhaps they were comforted by John Maynard Keynes:

…it is the long term investor…who will in practice come in for most criticism, wherever investment funds are managed by committees or boards or banks. For it is the essence of his behaviour that he should be eccentric, unconventional and rash in the eyes of average opinion. If he is successful, that will only confirm the general belief in his rashness; and if in the short run he is unsuccessful, which is very likely, he will not receive much mercy. Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.

Of course, the bubble burst, GMO saved/made their clients lots of money while most others were comfortably failing (read: losing money) the conventional way, and the assets came back and then some. In his piece, Arnott is quick to point out that

taking these steps is not comfortable. Comfort is rarely rewarded. Investors can move down the path toward this maverick portfolio, careful not to exceed their board’s or their client’s “comfort” threshold. This approach goes against human nature and invites second-guessing whenever it inevitably doesn’t work. Keynes’ oft-cited “reputation” quotation, in its more complete form, bears careful consideration.

This point bears further consideration. GMO clearly did exceed their client’s comfort threshold. That’s why so many left.

If we spend too much time as professional investors calibrating ourselves to our client’s comfort threshold there is significant risk that we will make sacrifices to our process, our investment discipline, and ultimately to our fiduciary duty of acting in our clients’ best interests. It’s not just a little ironic that the line between doing what is right for our clients and doing (or not doing) things that might make them fire us is a blurry one indeed.

Client-Manager Alignment

How do we deal with this paradox? For starters, there needs to be a high level of trust between clients and investment managers. This trust should be based on the obvious considerations like ethics and integrity, but also the more difficult ideal of alignment and understanding of the investment objectives and the process by which we are trying to meet those objectives. This requires open communication among other things.

Seth Klarman is unequivocal when he says “having great clients is the key to investment success.” For those unfamiliar with Klarman, his Baupost Group hedge fund gained an average of 17 percent annually from 2000-2010, a period in which the S&P 500 Index fell 1 percent annually. And while Baupost faced some criticism during the 1990s when the fund had a hard time keeping up with the raging and speculative bull market, the fund has returned 19 percent a year since it was started in 1982 (Klarman was 25 years old), even as it held more than 40 percent of its assets in cash at times. In an interview, he goes on to describe Baupost’s ideal client as having two characteristics:

1.) If we feel we have had a good year, they agree, regardless of relative performance

2.) When we call, asking them to consider adding new capital, they a.) appreciate the call and b.) add new capital

The second characteristic is important for Baupost because they often invest in illiquid securities or non-traded assets such as real estate. When prices are down, they want to have extra liquidity from clients in order to purchase more assets. Such was the case in 2008-2009 when Baupost doubled their assets under management to $22 billion after being closed to new investors for many years.

The subtext of point #1 is that Klarman’s clients know that his number one priority is to generate positive absolute returns regardless of the market’s direction. To put it another way, Klarman’s self-identified “key to investment success” is having clients who want what he is offering: a strategy that seeks out attractive returns for the risk that he is incurring without the expectation that he will outperform in every market environment. Indeed, he is clear that the returns they will generate are a function of the opportunity set presented by the market’s valuation and is not afraid to return capital to investors (whether they want it or not) as he did at the end of 2010 if the market is not offering abundant opportunity.

At a recent Grant’s Interest Rate Observer Conference, Klarman professed to “being surprised at how little cash we have.” 28% of the Baupost portfolio was held in cash. While 28% sounds like a large amount of cash (mutual funds currently hold 3.4% of their assets in cash) to most relative return investors– the expensive valuations present in the stock and bond markets have pushed an absolute return-oriented investor like Klarman to buy hotel properties in places like Charlotte, N.C. at a 7-9% cap rate, while keeping 28% of dry powder for an eventual return to attractive valuations in the public markets.

Bringing it all home: What’s your benchmark?

We should all strive to place less emphasis on the conventions of the day and seek to arrive at a fundamental understanding what really drives investment returns so that we can make smart decisions about where we put our money. We can not accomplish this however, without knowing what our future liabilities or objectives are and addressing as Arnott puts it, “the asset/liability mismatch, which leads to a risk that we cannot cover our future obligations.” For most individuals, these “future obligations” come in the form of a desire for lifestyle maintenance in retirement, the ability to leave a legacy, or give back to the world. These obligations tend to be absolute in nature– that is requiring a certain level of assets– independent of how much your neighbor is making on his portfolio or how much “the market” returned last year.

As Tom Brakke of the Research Puzzle put it:

Decisions large and small are off kilter because the looming shadow of benchmark risk overwhelms almost everything else… maybe they should consider a low volatility strategy, even if some “underperformance” in a bull market comes with it, since such a shortfall versus a benchmark is not really a risk that matters relative to other considerations… Many of the benchmarks are, in fact, false ones. I dare say that the S&P 500 is not a natural liability for many individuals or organizations to fund. Nor is some broader market portfolio. These are made-up constructs and should not be the prime guide for decision making. But the business of investing is tied to them, to its detriment and that of its clients (emphasis mine).

The bull market of the 1980s and 1990s provided the fuel for the relative return performance derby embraced by so many people and organizations today. In a consistently rising market, when nearly all returns are positive, the collective focus shifts towards relative returns and places undue importance of “false benchmarks” such as meeting or exceeding the S&P 500. The last 10 years has demonstrated the importance of remaining vigilant and keeping our eye on the true “natural” benchmark of earning absolute returns without being exposed to catastrophic of permanent losses of capital.

No comments:

Post a Comment